Today, I’ve got a special interview with Dr. Keith Barr. We talk all about everything from the effects of testosterone, cortisol, and the role of collagen protein in building muscle. What Dr. Barr has to say may surprise you.

The Flex Diet Certification is open for enrollment from June 6 to June 13, 2022. Go to flexdiet.com to enroll. If you’re outside of the enrollment window, sign up for the waitlist and I’ll notify you when it opens again.

Episode Notes

-

Dr. Baar’s background

- Testosterone research on muscle building

- muscle quality

- men vs. women

- Sex differences in effects of cortisol

- Are there strategies around cortisol for building muscle faster?

- Nutrition strategies?

- Would Dr. Baar suggest doing less frequent but more intense bouts of exercise?

- How Dr. Baar got interested in collagen research

- Discussion of upcoming collagen study

- Collagen synthesis

- Soft tissue injury prevention

- Find Dr. Baar: https://health.ucdavis.edu/physiology/faculty/baar.html

The Flex Diet Podcast is brought to you by the Flex Diet Certification. Go to https://flexdiet.com/ for 8 interventions on nutrition and recovery. The course is open for enrollment from June 6 – to June 13, 2022. If you are outside the enrollment window, sign up for the waitlist and you’ll be notified when the course opens again.

Rock on!

Dr. Mike T Nelson

References:

Baar K. (2014). Using molecular biology to maximize concurrent training. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S117–S125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0252-0

Baar K. Stress Relaxation and Targeted Nutrition to Treat Patellar Tendinopathy. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019 Jul 1;29(4):453–457. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0231. PMID: 30299199.

Davidyan A, Pathak S, Baar K, Bodine SC. Maintenance of muscle mass in adult male mice is independent of testosterone. PLoS One. 2021 Mar 25;16(3):e0240278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240278. PMID: 33764986; PMCID: PMC7993603.

Halson, S. L., Shaw, G., Versey, N., Miller, D. J., Sargent, C., Roach, G. D., . . . Baar, K. (2020). Optimisation and Validation of a Nutritional Intervention to Enhance Sleep Quality and Quantity. Nutrients, 12(9). doi:10.3390/nu12092579

Jerger, S., Centner, C., Lauber, B., Seynnes, O., Sohnius, T., Jendricke, P., . . . König, D. (2022). Effects of specific collagen peptide supplementation combined with resistance training on Achilles tendon properties. Scand J Med Sci Sports. doi:10.1111/sms.14164

Lis DM, Baar K. Effects of Different Vitamin C-Enriched Collagen Derivatives on Collagen Synthesis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019 Sep 1;29(5):526-531. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0385. PMID: 30859848.

Lis DM, Jordan M, Lipuma T, Smith T, Schaal K, Baar K. Collagen and Vitamin C Supplementation Increases Lower Limb Rate of Force Development. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2022 Mar 1;32(2):65-73. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2020-0313. Epub 2021 Nov 22. PMID: 34808597.

Langer, H. T., West, D., Senden, J., Spuler, S., van Loon, L. J. C., & Baar, K. (2022). Myofibrillar protein synthesis rates are increased in chronically exercised skeletal muscle despite decreased anabolic signaling. Sci Rep, 12(1), 7553. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11621-x

Paxton JZ, Grover LM, Baar K. Engineering an in vitro model of a functional ligament from bone to bone. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010 Nov;16(11):3515-25. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0039. Epub 2010 Aug 28. PMID: 20593972.

Pechanec, M. Y., Boyd, T. N., Baar, K., & Mienaltowski, M. J. (2020). Adding exogenous biglycan or decorin improves tendon formation for equine peritenon and tendon proper cells in vitro. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 21(1), 627. doi:10.1186/s12891-020-03650-2

Steffen, D., Mienaltowski, M. J., & Baar, K. (2022). Scleraxis and collagen I expression increase following pilot isometric loading experiments in a rodent model of patellar tendinopathy. Matrix Biol, 109, 34-48. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2022.03.006

Shaw, G., Lee-Barthel, A., Ross, M. L., Wang, B., & Baar, K. (2017). Vitamin C-enriched gelatin supplementation before intermittent activity augments collagen synthesis. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 105(1), 136–143. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.138594

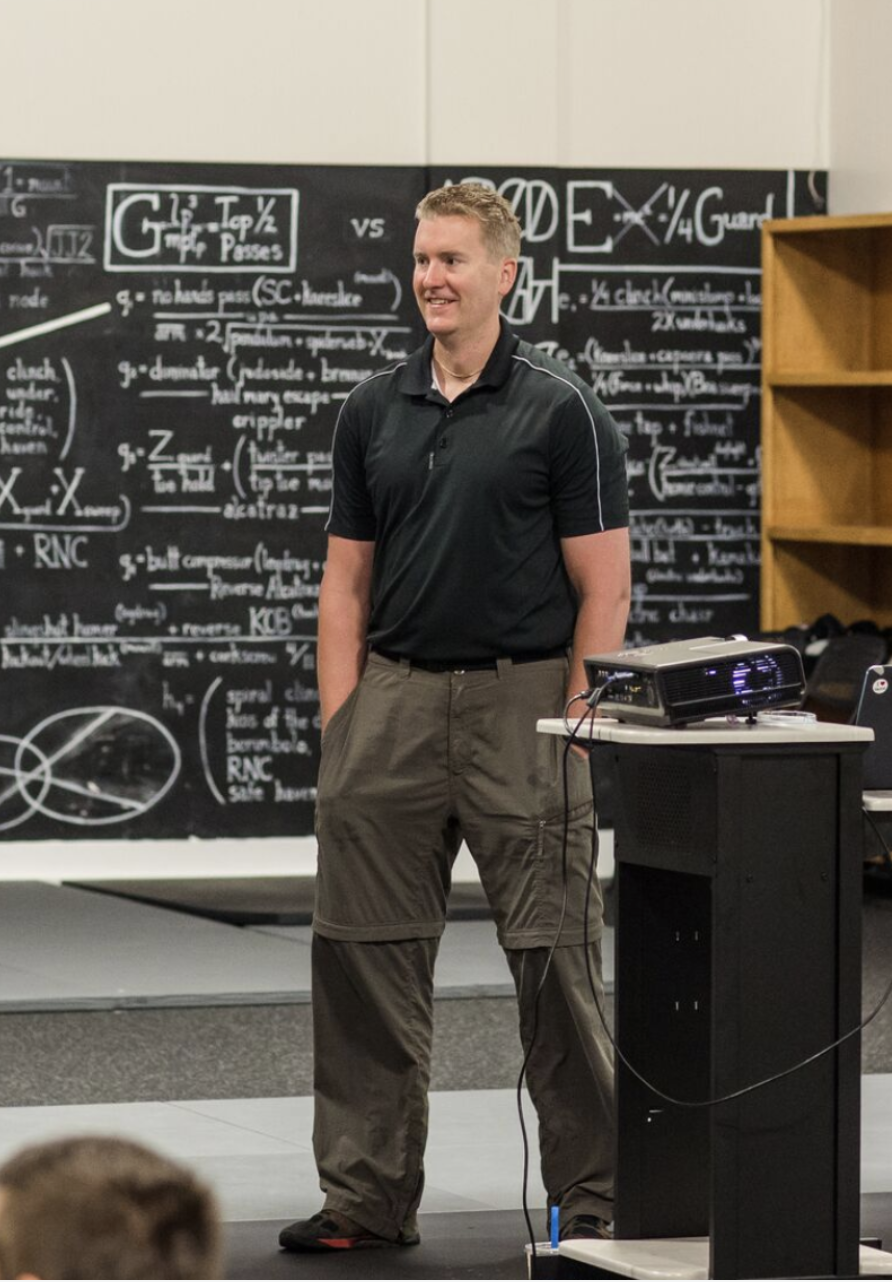

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Hey there. Welcome back to the flex diet podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T. Nelson. Today on the podcast, we’ve got a super special interview with Dr. Keith Barr. We’re talking all about testosterone, cortisol, and the role of collagen protein.

As always, this podcast is brought to you by the Flex Diet Certification. So if you’re listening to this right after this podcast came out, the Flex Diet Certification is now open for enrollment. It’ll be open from now when you’re listening to this through June 13 2022, at midnight. So go to flexdiet.com.

For all of the details and the information. If you’re listening to this, outside of that time, you can still go to flex diet.com. And you’ll be able to put your name on the waiting list. So the next time that it opens, you will be notified. And you’ll get lots of great information for free delivered right to the old inbox there. You go to flexdiet.com for all of the information.

We’ve got lots of great expert interviews there in the certification from the likes of Dr. Stu Phillips, Dr. Jose Antonio, and Dr. Eric Helms, Dr. Dan party, Dr. Hunter, and many, many more. So I tried to include lots of expert interviews, in addition to all of the coursework there just over 20 hours. So that if you want to take a deep dive and talk to actual researchers and practitioners on different topics within that, that’s all included there also.

Coming up next, here is an interview with Dr. Keith Barr. This is one I’ve been working on to do, honestly, for several years. I read his research and been following it for quite some time. And it turned out great. It is very technical at times, so you may have to listen to it a couple of times. Now, if you have any questions drop me a note. I did try to include as many of the references here as I could, but I was not able to get all of them. And we talked about everything from the effects of testosterone. This is if you’re in a normal level, versus a super physiologic level. And you may be surprised by what he says about the effects of testosterone for building muscle and a normal range. And the surprise is probably not really needed, which is pretty crazy.

We talked about the effects of cortisol. And in research, what you find is those who have the highest levels of cortisol are actually able to add more muscle. Even though cortisol is considered a catabolic hormone. We talked about nutritional strategies you can do to manage that differences between men versus women, especially related to cortisol, how this impacts intermittent fasting, and other periods of stress. And then we talked a lot about collagen. So collagen has been I’ve written about this in academic textbooks and papers before that, it was pretty useless. And this was looking only at sort of a muscle centric approach. So it is true, the collagen doesn’t really stimulate muscle protein synthesis at all. But Dr. Barr and others Dr. Shah have done some really interesting research showing that it may be beneficial for soft tissue. So if you have some soft tissue injuries you’re recovering from, or you just want to reduce your risk of them.

This is something that I’ve been using with my one on one clients for almost like three years now. So again, I don’t publicize everything that I do with one on one clients. But I think enough time has passed with this that I wanted to share all this information with everyone and I wanted to get it directly from the source who’s done a lot of this research. So we’ll learn how do you use collagen specifically for soft tissue? Should you change your training? Should you do different types of training? Now this can be especially beneficial for recovery from some kind of niggly injuries. This is something that again that I’ve used with one on one clients for quite some time. And again, anecdotally I found that it works really really well. So Dr. Keith bar talks all about that, and a bunch more.

Ssit back and grab your favorite beverage and enjoy this wide ranging talk. from Dr. Keith Barr. Hey, welcome back to the flex diet podcast. And I’m here today with Dr. Keith Barr. Thank you so much for taking time on the podcast today. We really appreciate it.

Dr. Keith Baar

Absolutely pleasure to be here.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. Today we’re gonna get into all things College and a little bit more related to maybe injury recovery and performance. But people may not have heard of you do you want to give yourself just a little background about how you got into research? And I know you do also very much applied stuff too. So I’m always fascinated by that of people who have running research and then also applying it in the, shall we say, the real world at the same time?

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, so. So what what I did is I started, I started in the applied field where I was undergrad at the University of Michigan, I became an assistant strength and conditioning coach. So I started as in that, in that kind of applied vein, and then I went on to do a Master’s at Berkeley, a PhD at University of Illinois, and then a postdoc at the at Washington University. And along the way, I was really focused on how exercise nutrition aging disease, alter the adaptation of muscle, muscular skeletal tissue. So how do we improve and optimize performance? Using exercise nutrition, and, and maybe hormonal interventions throughout the lifespan? So how does it change? How does our response change as we get older, all of those types of, of ideas, and some of the best things we can do are manipulate the loads that we use, as well as the nutrients that we supply our body with.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Great, and I know you did some early work on testosterone, also, if you wanted to touch on that, because I I think its role a lot of times is misunderstood. And there’s a huge difference between Are you hypo ganando. So you’re real low. Are you kind of in the middle what we’ll say, quote, natural area, and then if you use, you know, other special supplements to get to Supra physiologic level, because I think humans, we tend to think that everything is linear, but it’s it’s very much a non linear dynamic.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, so. So we had shown some of the work that Eric Davidian has done in in mind subroutines labs, where he was manipulating testosterone, both in male and female animals. When he did it in male animals. Basically, what he could do is he could castrate them at different ages, and without testosterone had no effect. Once you reach maturation, the only time they really had an effect is when they were during growth, so at their puberty, so they were still going through puberty.

The same thing is really true for the females when you’re supplementing with testosterone. So we add external testosterone, you need a secondary stimulus, you need either a resistance exercise, or you need pubescent growth, in order to see an effective testosterone floor. So for most individuals, who are adult, so they’re fully mature, skeletally mature, we’re not seeing a huge effect on on muscle mass until you’re really super physiological, that kind of thing that you only get, when you’re supplementing quite extensively as a performance enhancing drug user.

When you’re in physiological ranges, it doesn’t really have that much of an effect. Largely because, you know, most of the steroid effects are seen around 5% occupancy of the receptors. So most, most people who are not hypogonadal, or they’re going to be able to reach that level as men without really having to supplement without really having to worry about it as you get older, that didn’t seem to have a really positive effect. And the thing we always see with testosterone is it decreases breakdown in muscle. And that’s the primary thing that’s happening in muscle.

And that’s just making your muscle quality go down, you might have more muscle, but that muscle doesn’t have as good quality because that turnover rate, how quickly we can kind of get new proteins into to to replace the old proteins. If we slow that down, all we’re doing is accumulating damage. So we accumulate oxidative damage lipolytic damage, all kinds of different things that happened to your proteins posttranslationally that can have a negative effect on how that protein performs. So if we decrease protein degradation in the short term, yeah, we might have a beneficial effect, but in the long term is going to have a negative effect. And we see that because men’s muscle quality isn’t as high as women’s when we take it down to the her cross sectional area.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

So if you’re really thorough rules and ethics aside for right now, and you’re getting close to, let’s say, the high end of weight class board, where speed and power our primary eminent would using anabolics. At least testosterone will keep it to that, could that be a negative at that point, because you may be adding weight, that doesn’t function quite as well.

Dr. Keith Baar

So in a situation like that, the benefits are actually not happening really from your muscle, they’re happening from the central changes to the aggressiveness that’s happening. So when you’re going to do strength, speed, or power, if you’re hyper aggressive because your brain is is, is easier depolarized, which we know that happens with testosterone. So you can activate things really, really quickly, that’s going to potentially have a beneficial effect. The other thing that we see in our connective tissue work is when we add testosterone, it makes the connective tissue stiffer. And that’s really where we think a lot of the performance benefits are happening, those two components, the brain is going to allow you to make a decision quicker, and to do a movement faster, and the stiffness of your connective tissue is going to go up. And so those two things together are going to increase your rate of force development.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Ah, very cool. I like the party you said about if you’re in the normal range, going from, say 450 to 850, you’re not going to see a huge difference, which I think is probably kind of surprising to most people. I mean, I would agree. And most of the literature supports that even though we don’t have a ton of data on that. And humans think Bazan did some stuff in the 90s, where they chemically castrated some males and then tried to supplement them back in a couple of different areas.

Dr. Keith Baar

There’s there’s good data from prostate cancer patients where if you, if you use if you use drugs to block testosterone completely, they are still able to grow their muscles just the same as people who don’t have that have that negative effect on their testosterone. So you could be at zero testosterone, or very low testosterone as a man, you can still gain muscle mass from the resistance exercise and the rate at which you gain that mass is the same as somebody who hasn’t been altered by those drugs. So and so that’s that from the from the prostate cancer literature, when people are going through chemotherapy that are designed because that, that the prostate is so an androgen intensive. So it’s so dependent on the androgens for growth that it’s commonly used to drop testosterone as low as possible. You can still gain muscle mass in that situation. And so there’s good there’s good data there. There’s good data and in the rate at which women add muscle mass and strength that said, yeah, that was my next question really get into that much.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Because I think in mature males and females, the rate of gaining muscle is similar if you control for other factors, even though they have much, much less testosterone than males.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah. And there’s good work from keratin, where he showed that there is strength, that women’s strength will increase faster or greater than males, the baseline is lower. But they respond to resistance exercise as well, if not slightly better than men.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

And are they responding better, because they’re out a little bit lower, have a baseline are there some other factors there.

Dr. Keith Baar

Maybe you’re there at a little bit lower of a baseline, but they’re also and so that’s probably sociological, that we don’t encourage women as much as men to perform strength exercise, so they’re not necessarily starting with as much muscle mass. But then she now has shown that women have a higher protein synthetic rate. And like I said that testosterone lowers break down, so that women have a higher breakdown rate as well.

So the turnover rate of a woman’s muscle is actually higher than a man’s. But one of the things that testosterone is doing is explaining to the glucocorticoid receptor and inhibiting cortisol, some of the cortisol effects. So one of the things we see is under stress or under high levels of, of glucocorticoid. So these, these mineral, or sorry, these steroid hormones that are supposed to drop muscle mass, far, far more effective in women at dropping muscle mass than men, because without the protective effect of testosterone, that glucocorticoids the cortisol in the system is going to drop muscle mass much faster. And Sue Bodeen and they furlough here at Davis showed that really nicely in animal models were when you add, you know, any of these glucocorticoids to males and females that the females dropped muscle mass much faster than a male.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

So what a kind of an extrapolation of that be that females may be more sensitive to the effects of overall stress and related to muscle mass or is a little too much of a leap.

Dr. Keith Baar

In so far as that cortisol will go up with stress. They’re the bigger The bigger issue for your listeners, if they if they’re looking at metabolic flexibility, I’m sure that a lot of them are doing things like time restricted feeding and or some fasting. That means what it means to us is that the cortisol levels in a woman are gonna go up the same as they are in demand, they’re gonna reach their highest rate before breakfast right before whenever you break your fast. And it means that the women’s muscles are more prone to losing muscle mass and from fasting than men are. So they’re not necessarily going to see this as much of a beneficial effect as a male would, from doing some of the time restricted feeding or, or intermittent fasting that that a lot of your male listeners will have tried at least.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s super interesting, because I have had some females do shorter fasts, but only maybe once a week, once every other week. And I can’t think of a single circumstance where I’ve had females do longer fasts, like a 16, eight, or those types of approaches where I’ve had some guys have some pretty good success with that, I would say in general, at least anecdotally, males tend to do better with longer fasting. And I’ve always wondered if that was something more physiologic, which sounds like it could be or other factors.

Dr. Keith Baar

But you also see other hormones that are really important in in protein fasting as well like FGF 21. So I have a colleague, Karen Ryan, and she injects FGF 21, into the brains of males and females, and then she gives them access to the individual macronutrients. So she puts a plate of protein fat or carbohydrate out. And when you inject FGF 21 into the brains of males, they will go and almost exclusively eat protein. And the females won’t do the same thing. So we actually have very different drivers for both both our adaptive response, our metabolic response to fast, but also in our, in our cravings, that results from the fast. So whereas males might crave a little bit more protein rich food, females don’t have a specific as much of a specific crave in that way. And that could also play a role in how much muscle mass is maintained in these longer or intermittent type fasting.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s very cool. Because, again, anecdotally, I’ll ask clients, like when you get super stressed, like, what foods do you crave? And guys typically will be, you know, some foods, but you know, it’s not uncommon to hear I just want like a big steak, right? We’re rarely do I ever hear females say that, I’ve always wondered if there’s something physiologically or if it’s just more of a societal convention. So sounds like there may be something to that physiologically.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, it’s probably a little bit of both. But there is definitely a hormonal, a neurocognitive change that results from some of these hormones that are usually produced by things like, like the, like the bile acid components that you get FGF 21 from. And so so because there are these kind of cues that we’re getting from the physiological response to either feeding or fasting, there are going to be sex differences that are going to have significant effects on on our muscle mass, and as a result on our basal metabolic rate and other things.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Awesome. And if someone wanted to, let’s say gain muscle or lean body mass, I know I’m kind of using them interchangeably at the fastest rate without any exogenous drugs. Is there some types of strategies they should do around cortisol or other methods?

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, absolutely. So so the interesting thing is that the cortisol is probably the best predictor. So the higher the cortisol, the better, you are going to be gaining mass

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Seems like the inverse of what most people would guess, right?

Dr. Keith Baar

It is the inverse of what people would guess. And probably the best predict the best reason the best rationale as to why is that what you’ve done is you’ve done the hardest exercise. So that’s the greatest stress. And so what we know is if we want to build our muscle mass, what we’re going to do is we’re going to lift any weight to failure. So it doesn’t, you don’t have to lift a huge weight, you can lift a relatively lightweight for yourself. But as long as you keep going until you can’t lift it anymore. And the key there is that you don’t rest at any point, you just keep pushing, keep pushing, because what we know is that and what Stu Phillips has shown quite nicely is that what happens when we get a muscle to failure is that’s the only time in humans where we recruit all of the fibers within the muscle.

So all of the fibers within the muscle, get that molecular signal that’s going to tell the muscle it’s going to now want to get bigger. And so if we don’t go to failure, we’re only getting part of the signal. So many of the fibers don’t actually get the signal to grow. But at failure, we’re recruiting all of the muscles we’re giving a signal to all of the muscle fibers within the muscle We’re working. And that’s what, that’s why we use any weight to failure.

It doesn’t matter light or heavy, you can get bigger by using anything and lifting into failure, and then supporting it with a good high quality proteins that have that are complete proteins. So whey is the gold standard, because it’s easily digestible. But anything that’s going to be a leucine rich protein that’s going to have all of the nutrients, it can be plant based, it could be animal based, it doesn’t, it’s not a huge difference. But what you’re looking to do is you’re looking to support that strength training with with that protein dose. And those two things together, we know the molecular mechanism.

So what we had shown very early on, during my PhD is that how big your muscle get is directly is gets is directly proportional to the short term activation of a protein kinase called mTOR. complex one, and that one’s also activated by amino acids. And they activate mTOR complex one in different ways. And so what we know is that the two things together additive, so when I do my, my lift, and I get that signal, I get that failure, I get that signal of tension across that muscle fiber, that muscle fiber is going to change that tension into a chemical signal, that’s going to turn on into a complex one.

And the way that it does that is different than the way that amino acids are going to do it. And so the result is when we do them together, we get an increase a further increase greater than what you would get with either feeding alone or with with strength training alone. And so combining those things together is going to give us our biggest growth response.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Very cool. I think some of the stuff from Nick birds lab or Nick bird, when he was working in Stu Phillips lab showed, you know, as light as 30% of one RM, which I it’s much lighter than I think most people would realize, but they did that with leg extensions, again, that exercise was taken to, you know, momentary failure, or you couldn’t move the weight or whatever definition we’re using for failure in this context.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, they go to positive failure. And when you get to positive failure, you got that beneficial effect, the biggest effect, whether it was 30%, or 90%, of one rep max. And then they did the follow up study looking at 30%, or 80%, they train them. And they found that the increase in muscle mass was the same between them over I think it was an eight or 12 week training period. But what they found was that the increase in strength was greater for the 80%. groups. So they had a couple of 80%. So when you’re lifting 80% of your one rep max, you got a bigger increase in strength, but the muscle mass was the same.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, and I saw Stu here a couple of weeks ago, he said to say hi, by the way, very good. And he was saying there’s some even newer studies where they then took the group that did say a low like 30% of one around, and then gave them a couple practice sessions on what they were going to test them on. And then he said that the strength of difference between those two groups got to be even less than so there’s even some debate about if you use some other method, and maybe you can add some muscle that way, you know, how long would you need to train that, quote, new muscle to impart strength changes to attend to.

Dr. Keith Baar

So the neurological adaptations are going to be very, very quick. They’re the fastest adaptations that we have within the within the strength paradigm. But once you make those neurological adaptations, you’re also going to have other structural changes that are going to be important for how well you transmit the force. And so yeah, so what we say is that if you want to get stronger, you lift a heavyweight, if you want to get bigger, you lift any weight, you go to failure.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

At some point can you make up for not going to failure by just doing enough physical volume to compensate for that if you have more time, and let’s say your goal is kind of more strength and hypertrophy at the same time.

Dr. Keith Baar

So you can go the volume component is important for size. It’s not important for strength. So it doesn’t look like we need to do a lot of volume if we want to increase strength. But if you want to increase size you can do you can do less weight and do a lot more volume. And a lot of people in the field know this because a lot of a lot of bodybuilders. That’s exactly what they do. They love to be in the gym, that’s their job.

In between sets, they talk to every single person in the gym, they’re going to spend six hours in the gym. frequency, intensity and duration is what we manipulate. So if you want to have your duration be super long. You just do it with a lower intensity. And so that’s basically still right within that overload principle that is really the key to to growing muscle bigger and stronger.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

On the catabolic side, is there anything we should look at nutritionally to maybe indicate that I know there’s always a bunch of talk about carbohydrates immediately after training. And then I think it was through his lab again showed in terms of insulin release, if you’re just having 20 to 40 grams of whey protein, you have enough insulin release to kind of stop the catabolic process. So maybe from that side, it’s not as important as we thought, obviously, you’d be replenishing glycogen if you’re going to do a session within a short period of time, right after, which would be a different circumstance.

Dr. Keith Baar

So the classic, the classic study there was by Kevin Tipton students who was on that paper as well, where they were they fed either all amino acids are essential amino acids. And when they just fed enough of the essential amino acids, they got a decrease in degradation. Because a lot of times what we’re looking at for degradation isn’t something where we’re driving degradation, or we’re inhibiting degradation through the insulin stimulation, because insulin stimulation for the first six hours after exercise is inhibited.

And so after resistance exercise, and so what we’re actually getting, as far as the degradation is a degradation is used to drive synthesis, after strength training, because what we’re looking for is we’re looking for essential amino acids, if we don’t have a source from the diet, because somebody’s doing it’s fast, and we have to break down protein in order to free up amino acids, specifically, the essential amino acids. And so what have tipped in 1999 papers show that is if you bring up the essential amino acids, you drop protein degradation, and that that doesn’t necessarily need any insulin response, there is some arginine in that essential group that he gave to give it maybe a little bit of insulin, but the insulin component, because when we do heavy exercise, or we do strength exercise, we get that load across the muscle.

Troy Herm Hornberger shown that when you do that, you activate a different system that’s parallel to the insulin system. And that’s activating mTOR, in an in in a way that doesn’t need insulin or IGF one. And then what you get is you get feedback inhibition. And so my former PhD student, Lee Hamilton had shown that after exercise, the Association of either Iris one or IRIS to these two insulin signaling substrates goes down, the association with the with the insulin receptor goes down. And with a PI three kinase, they go down.

So what you’re doing is and and Rennie Koopman showed long time ago now that what happens after lifting heavy weights, is you get a period of insulin resistance that lasts maybe three to six hours while you’re getting this feedback inhibition on insulin signaling, because you don’t need it because you’re able to activate these systems independent of insulin. And then 24 hours later, you actually have an increase in insulin sensitivity, because you this whole system has kind of reset insulin since insulin signaling to some degree. And so it allows you to then re to get a bigger stimulus from the same from the same amount of insulin. And so we think that that’s one of the really important things that resistance exercise does is it resets a lot of the the signaling cascades that are downstream of insulin, or downstream of some of the metabolic flexibility things that we look at, because we just had a paper come out where we did four bouts of exercise over two weeks.

And then 72 hours after the last bout of exercise, we looked at protein turnover. And we looked at signaling through mTOR, an mTOR signaling is significantly lower in the muscle that you’ve exercised four times over those two weeks, but your protein synthetic rate is higher. So what we’re doing is we’re dropping a lot of the baseline level of mTOR activity is going down, that baseline level of certain aspects of insulin signaling are coming down. But then what we’re doing is we’re returning the ability to signal the next at the next meal or at the next bout of exercise. And so what we’re doing is increasing the the, what we call the dynamic range of the system, what we do is we we haven’t go really we activate the system really, really at a high level.

And then for two or three days, it’s going to actually go down below baseline, and then we’re going to be able to activate it again. And every time we have a meal because we’ve got this greater dynamic range, we take more of the protein that we eat, we make it into muscle in that space. And Stu again is shown that 24 hours after your last resistance exercise, but you’re still better at building muscle than if you didn’t do the exercise bout yesterday. And so a lot of that is because what we’re doing is we’re we’re modifying the dynamic range. We’re dropping the baseline of things like mTOR activity and insulin signal And then when we get that signal comes back, because we eat, we get insulin, now we’re going to have an insulin signal, now we’ve got this much greater range, we go from a lower starting point to the same level of stimulation, that change is much bigger. And that means we get a bigger biological effect from the same state signal.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

And so the nine sound effects you’re talking about are related to the non insulin mediated uptake. Category, I guess you could say, is that correct?

Dr. Keith Baar

So there’s a lot of the non insulin mediated stuff. So yes. So, you know, we know that the insulin signal for glucose uptake can be can be basically replaced by an contraction based signal, we know that a lot of what insulin does is change blood flow, get blood flow to go to the tissues, where it’s supposed to where we’re supposed to store amino acids and sugars. And that’s to our muscles and certain fat depots, when we do exercise where we don’t need the insulin to change blood flow. Now that exercises change blood flow by producing metabolic byproducts. So we have greater blood flow. So we don’t need as much of the insulin effect to get more of the substrate into the tissue that we want it to go to.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Very cool. And the new study you were talking about, were they I think they did heavy stimulation for a shorter period of time. If we were to translate that into humans, and assuming that’s the same, would that’d be an argument for doing maybe less frequent, but more intense bouts of exercise then to try to raise that ceiling effect? Or what would that look like if you could translate it into human work group? And probably like intermediate level athletes? So not beginners, but people who have been, you know, training for a while but not elite level athletes?

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah. So. So yes, I think that, that people get into the same routine of their exercise training. And so we adapt to that. And so it’s less and less of a stimulus each time. And there’s a Japanese group that shows if you do the same exercise over time, and our new paper, as well show that even the second bout of resistance exercise, where we saw mTOR activity go up 20 fold after the first one, six hours after the second one, it goes up five fold, three, three to five fold. So we’re not seeing that huge response we saw in the Japanese group showed that over time that those individual responses to the exercise are coming down.

But if you take a two week break, and you do the exercise, again, bang it, there goes the that molecular signal comes back. So So there’s two ways you can do it, you can take a little time off and then come back and hit with that with the same type of exercise, you’ll get a bigger stimulus from that, or what what’s more, kind of what needs to happen more for, for people who just go out and train the same way every day, because you just have to throw in, say, 20% of your sessions, or 20% of the time that you’re going to be exercising at a at a much higher intensity.

So adding those high intensity intervals is going to have a huge effect. And we know that from work from from the Buck Institute, Simon mela have had shown that when you lift weights, or when you do high intensity interval training, that that the transcriptomics. So the all of the messenger RNAs within your muscles, if you’re older, they look like you’re younger, again, because that high intensity exercise that’s getting outside of the comfort zone, that’s giving you a greater stimulus to see things like muscle growth response genes, insulin signaling genes, mitochondrial genes, they have a much bigger effect, especially in an older population if you do high intensity interval training. And so So yes, I do think that manipulating, manipulating that intensity is a really important thing to do for all levels of athletes, and even athletes who are just training for life.

So they’re not going to train for any competition, they just want to feel like they’re still making progress. They’re still making the changes towards their goals. Those are the end goals could simply be healthy body, and low body fat or whatever it is. All of those things. The idea of going high intensity throwing in 10 to 20% of the work that you do as high intensity work is absolutely essential.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Now that matches a lot of Martin Caballos work he’s done some stuff on that for several decades. And so for practical area would you look at like 20 to 3040 seconds, like a Wingate type protocol where you’re going as hard as you can more on the complete rest and then try to keep that quality of work high again when you do the second dinner.

Dr. Keith Baar

So you can do it, there’s any number of ways you can do it, what you’re looking to do, you, there’s three areas that we’re adapting really well to, to endurance exercise. One is our long slow endurance exercise. And the other two, windows are our sprint intervals. And our high intensity intervals, sprint interval is between six seconds and 30 seconds, you do those six to 32nd intervals, you’re using ATP faster than you can produce it.

Because you’re going from stored phosphogypsum to glycolysis, you’re you’re at that transition point between two metabolic systems. It’s like if you’re driving your manual transmission car, and you’re accelerating, you have to pause for a second while you put in the clutch and you shift, that’s what your body is doing to some degree. So at those transition points, you’re using ATP faster than you can produce it. And that’s going to give our body a signal. The second transition point is between glycolytic and metabolism and oxidative metabolism, that’s happening in about one to three minutes. So we’re looking at those those intervals at like 32nd intervals, two minute intervals, those are great intervals to do.

And those are the intervals that are going to give us those metabolic signals those things like ATP. So ATP consumption, ADP is going up, ADP activates the ANP activated protein kinase. And we get a really important signal from that, when we go long for long time and we go at a relatively low intensity, that long, slow distance, we get a different signal that’s driving the adaptation that we’re making. And that’s a calcium based signal. And so that signal is likely cam kinase base. So now we have two different signals, one’s an intensity signal, one’s duration signal, we are, we tend to be really good about the duration signal, especially if we’re cyclists or swimmers or we can get in there and go for a long time.

Getting that intensity signal is is something that we’re less proficient at, because it’s more painful, it hurts to do you know, and so it is not the fun one, it’s the one that makes you feel like you’re gonna vomit at the end. And so people shy away from that one. So when we’re trying to do this, we’re trying to mix these two signals in. And we mix these two signals in in such a way as we can maximize the adaptation and minimize the mechanical input impact. Because especially for running, if we’re going to do a lot of high intensity running, the impact force is going to be much higher.

So our mechanical load is going to be much higher, the likelihood of us getting an injury is going to be much higher. And so that’s not necessarily where we want to do it. We want to do it when we’re rowing or cycling or swimming, where we’re not having as much of an impact force. You can do it with the running but now your percentage of your overall percentage of high intensity work has to be lower if you’re a runner, than if you’re a rower swimmer, cyclist.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, I’m a big fan of the rower because a lot of my online clients, they’re not training to be sprinters. And I don’t know how much I trust them to run full out at 90%. And even if they could that the impact over time, it’s like you’re looking at the cost benefit ratio. If you’re going to be a sprinter then yeah, of course, it’s specific. But if you’re not going to be a sprinter, I think you can use other modalities and still get that high intensity point without mechanical trauma also. Yep, know exactly. And probably a good time to shift gears towards collagen. How did you get interested in in college and research?

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, so we weed free. For years and years, we’ve been engineering, musculoskeletal tissue. So I started doing this with Bob Dennis, University of Michigan, where we would make little muscles in addition, Bob was is, is this crazy engineer guy who’s smarter than anybody else in the world that I know. And he, he had come up with this idea that when you do deep space flights, you’re going to need a motor. And that motor needs to be able to repair itself. So what would be perfect is if you had a muscle that could produce all of the movements that you are going to need in order to have like some tenure long flight.

And if something went wrong with the motor where it didn’t work, it would actually repair itself. And so his idea was if we could create, if we’re going to engineer these muscles, we’d have these motors that can be tuned to do different things within, you know, a body or a spaceship or whatever. And so he’s got great videos, you can still find online where he’s got little fish that are floating in it. And he’s got two little engineered muscles on either side of it. And he then could contract them alternatively and cause the fish to swim around. So So I went and worked with him for a postdoc and I was engineering muscles.

But when we put those muscles onto those little fish or onto any other kind of machine, they would always fail at the interface where we just tie them on. So they would always pull out or they would always have failures there. And we realized that what we didn’t have is we didn’t have a working tendon. And so what a tendon does, and so with Elena Ruda there at Michigan, what we what we showed was that tendon is a variable mechanical tissue. So we were we were doing these things were at the muscle and of the tenant is very stretching the bone and it’s very stiff. And that allows me to attach that stretchy muscle to a stiff structure.

And so we started to think about, oh, while we engineer all these muscles, we should engineer some tendons and ligaments. And so we started doing that. And then I moved my laboratory, my first lab to Scotland and I had a PhD student there, named Jennifer Paxton. And, and what we were doing was engineering. We were trying to engineer these ligaments, these tendons. And we, we said, well, if we’re going to have a bone, a tendon, and then a muscle, that’s three, that’s three tissues, it’s really hard to do. So let’s just start by making a bone attendant and a bone.

And that’s a ligament, bone to bone. And so she started engineering ligaments. And what we found really early on is that if we wanted to make a strong ligament, we had to add Prolene. And we had to add some of these other essential or amino acids that aren’t that aren’t necessarily found as at a as high level as we need it. And so when we added Prolene into the mix, we got a big increase in in the strength and the stiffness of our ligaments. And so I did some simple searches around to see what are proline rich foods and gelatin came up as a proline rich food. It’s, you know, it’s just collagen itself where the collagen has been boiled to produce to produce the gelatin. And so it’s still forms a gel, and it’s really, it’s really good that way.

And so what we, what we had figured is that, well, if this works in our little engineered ligaments, that these that these, that when you give Prolene or when you give glycine at high levels, there’s there’s a group from from Brazil who just gave lots and lots of glycine, and they saw that the tendons ligaments got better. So we figured that this might be a way to do it just by giving dietary collagen. And so we started by doing that we would take we would feed people collagen, or gelatin, we would take their blood and put it onto our engineered ligaments. And before you had the collagen and the vitamin C with, so your overnight fasted that blood medo alignment, it’s really weak. But the ones that you got an hour after eating the collagen, or the gelatin that made a much stronger and much more college enriched tissue. So that was telling us that maybe there’s something interesting there.

And then we did a study together with Greg shot the Australian Institute of Sport where we fed people for three days, we fed them either a placebo five or 15 grams of gelatin, we had them jump rope, six minutes an hour after. And that’s because we had using our engineered ligaments, we’ve shown that that connective tissues adapt really well to short periods of activity, that if you do an hour’s worth of exercise, your connective tissue is going to turn on, get maximal around 10 minutes and then turn off. But even though you’re continuing to exercise by 60 minutes, the cells aren’t getting a signal that’s positive.

And so we were just doing those short periods of activity. And over the 72 hours, when we gave them 15 grams of gelatin, we could double the rate at which the bones within those subjects were producing collagen. And so so that was telling us that there was potentially something there. We hadn’t done other proteins we just did placebo control versus gelatin. The five grams didn’t give us enough, but the 15 grams gave us gave us a nice effect. And so so we’re actually starting a study right now where we’re going to do pretty much exactly the same thing. We’re going to compare our hydrogen hydrolyzed collagen to whey protein.

And to the third thing we have is we have a vegetarian collagen, made by this made by a company out of the bay area here called gel Torre. And what it is is a recombinant collagen that’s made in bacteria. It’s the only form of collagen in the world.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

It just mimics the amino acid profile.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, it’s got the same amino acid profile. So they they build up this and they use it already for cosmetics or the collagen is used in cosmetics. And so now what they’re looking to do is see whether that can be used as a supplement in a dietary supplement for people. And so we’ll have those three proteins compared to placebo control in a bunch of men and women and we’ll be able to see if is it just any protein or work so the whey protein is just as good as collagen? Or is the collagen important? And is there something special about animal collagen? Or can we just take in this recombinant protein, which is never been in an animal? And can we get the same thing from just having those amino acids? So I think he’s gonna be a super, it’s a super cool study, we’re starting to recruit. So if your your listeners are in the Bay Area in in the Davis area want to be part of it, they’re more than welcome to, to reach out and and join the clinical trial. We should have the clinical trial up on clinical trials.gov this month so that we can and our recruiting is starting.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s awesome. And it sounds like that may settle the debate between you and Stu about college and versus way.

Dr. Keith Baar

I don’t have any debate with still because I agree with him that it’s not great for building muscle because it doesn’t have any Scott almost no leucine it doesn’t have it’s not a complete protein. The question that I have is whether there’s something that the cells within connective tissue are getting from, from either the amino acids or some of the other kind of limited amino acids that you see in college, and that you don’t see in any other that you don’t see in any other protein. And those are the hydroxylated forms of amino acids. So hydroxyproline and hydroxy, lysine, some of our data would suggest that those those kind of modified amino acids are actually giving a signal to cells, which could be important for the synthetic response that we see in response to to dietary collagen.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, that was my next question of how much do you think of that is providing raw materials for building blocks? And then you’ve got the stimulus of exercise and potentially more blood flow to areas that don’t get a ton of blood flow? And or is there some other downstream effects from the college and that’s signaling different things to go on? Or combination of both?

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, so So the interesting thing they told you is that when we take people’s blood before and after they eat dietary collagen, and then we put it onto our engineered ligaments, the ligaments get stronger. And this isn’t a situation where we’ve actually got five times the physiological level of amino acids in the media already. So we’re adding 10% of the meat, we’re adding 10% of the volume as the serum. And we’re getting more collagen synthesis, we’re getting stronger ligaments. But we’re not adding a lot of glycine and proline. And so what that’s suggesting to us is that something else in the collagen is actually having the the beneficial effect. And so we know that the vitamin C is important, but that’s in all of the different groups.

So the question then becomes, what is it? Or is there something special about some something that’s within that dietary collagen? That is driving this increase in collagen synthesis? And I think that that’s the really important question that we were really keen to answer with this study that we’ve got going on now. Because not only are we are we going to have whey protein, but we’re going to have this, this collagen that doesn’t have hydroxylated proteins, right.

And so if those hydroxylated proteins are important, we shouldn’t see that what collagen is better at stimulating collagen synthesis than whey protein. And it’s also better than stimulating something that has the exact same amino acid profile just doesn’t have the hydroxyl lations. So it’s going to be a super cool study in that way, because it has the potential to really pull out mechanistically, what’s going on.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, that’s awesome. And so one thing I’ve done with clients based off of your research, especially with Dr. Shaw was add 15 grams of collagen to their whey protein, about 40 to 60 minutes before exercise with some vitamin C thinking, yeah, maybe I’ll hit two birds with one and two stones, I’ll get the potential soft tissue effects per se, and then get some of the muscle effects per se, I assume you would generally agree with that in terms of practice.

Dr. Keith Baar

So it depends on what we’re trying to target. So if you’re trying to target muscle, we’re totally fine with adding it afterwards. Because the reason that we put it in beforehand when we’re looking at bone and tendon and ligaments, is because they don’t get the same kind of blood supply that the muscle does. So if we’re looking to fix a say, you know, we have a hamstring pull. So somebody’s pulled their hamstring, it’s pulled off, or it’s been surgically repaired or whatever, and we’re repairing that tissue. Now what we want to get is we want to get both a muscle signal and a and a connective tissue signal.

There’s going to be blood flow after the exercise that we do because that muscle is already pulling in blood flow. And so now we can do that as a supplement that we just do after together with the protein no problem. If we want to target it, specifically the tenant, then what we’re going to do is we’re going to put it in beforehand. And you can do it together with whatever you want to do it together with but yeah, we’re going to try and get it in about 40 minutes to an hour before Forehand, just so that when we’re pulling on that tenant, and we’re squeezing all the liquid out of it, and then we’re relaxing, and we’re squeezing, and we’re relaxing, we’re getting that rhythmic movement through that tendon, we’re going to get more fluid flow, and that more fluid flow is going to pull more nutrients into the, to the proximity of the cells.

And we’re gonna get more of whatever signal we’re hoping to get there, using that kind of load as a way to target our nutrition to where we want it. So yeah, the way that you do it sounds fine. The way that we would kind of tweak it a little bit as if we’re looking for a muscle signal, yeah, finally give it afterwards, we’re looking for something that’s more tendon or ligament based, we’re gonna give it or cartilage base or bone base, we’re maybe going to give it beforehand.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Got it? And would there be any downside to adding like, six to 10 grams of essential amino acids with the collagen beforehand?

Dr. Keith Baar

Not at all. Not at all. And it might be something where adding the whey protein together with a college and it’s gonna give us a better response, because the whey protein are going to have all of the other amino acids that aren’t necessary. The thing to remember is the collagen is a really simple protein. It’s basically three, it’s basically two amino acids, its glycine and proline make up two thirds of the amino acids within collagen. So the sequence goes glycine, any amino acids and any amino acid then Prolene. So most of what we see are glycine and proline. So that’s one of the reasons why we are giving a dietary collagen is because if we give whey protein, it’s a dairy based protein, it’s a great protein is a complete protein.

But what happens is after exercise, you’ll see a drop in glycine within the body. And it’s possible that we’re getting a little bit of a limitation based on how much placing is there because it’s not as glycine rich as some of the connective tissue. And there’s some really nice work coming out of Luc Van loons lab that’s showing that after resistance exercise, there’s higher rates of protein turnover in the matrix than there is in the muscle.

So the matrix is actually got more protein synthesis response to exercise than the muscle does. And we’ve seen that in a number of our studies that where when we give a stimulus for muscle to grow bigger, we actually see collagen concentration go up, which means that the collagen is increasing at a faster rate than the muscle protein is increasing. And we’ve got a colleague in France who inhibits collagen synthesis when he does that. And what he shows is that you drop 50% of the strength gains or loss by inhibiting the increase in collagen synthesis. So you really think that the matrix is important, whether it’s sensitive to collagen as a dietary supplement, we it’s far too early to know. But we do know that the matrix is really important for the functionality of that muscle, the muscles ability to transmit force and to become stronger.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I think it was then the enzyme that also had a study looking at different tissue turnover rates that they did from some surgeries showing that basically, the turnover rates were much faster than at least what I thought, because I had heard the old thing, which is kind of been sort of disproven now that, you know, muscle will turn over in 90 days and soft tissue takes like nine months. We’re all the newer data. And you’re suggesting that that might even be inverse, that some of the collagen processes may be turning over faster than muscle.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, so that that study that Smeets was the first author on base, right? What he what he shown is that protein turnover in the ACL was actually twice that of the quadricep muscle, right? And that patellar tendon was almost the same as the ACL. And we know that is load dependent, because when he looked at the PCL, the posterior cruciate ligament, it had the same amount as muscle. So the loading because the PCL isn’t loaded a lot, the ACL is loaded quite a bit.

That’s where we’re getting that dynamic difference between those two tissues. But yeah, it was quite it was quite, you know, illuminating to see that we also have to understand that yes, there is real good, very, very good data from Michael Karis Group from Katsuya henna, Meyer, using the bomb pulse that shows that look, collagen turnover in the core of our, of an Achilles tendon doesn’t doesn’t happen to to a great degree. We might be because again, that’s using this radioactivity that you would find in the environment. It might be that we’re able to recycle really well, all of the protein amino acids within the core.

And so we don’t see say, a breakdown, or we don’t see turnover overall, but we’re able to recycle those amino acids or it means that the core isn’t changing, and the outside of our attendance is changed are changing quite a bit. And so we can’t make any grand conclusion as to which one it is yet, but we do know that If that like metal, metabolically, the outside of attendant is far more metabolically dynamic than the inside. And so it’s possible that we’re seeing differences through the tendons from the core to the outside, and also as a function of things like exercise and nutrition and other and other components.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, that’s fascinating. And then you also wonder about all the free case studies, you see of weird Achilles ruptures that, you know, quote, unquote, appear to happen out of, you know, nowhere, and there’s different like Levaquin, and different drugs seem to target Achilles heel injuries more often. And yeah, yeah.

Dr. Keith Baar

So there’s a, there’s a whole bunch of things. Within that one of the ACE inhibitors is Scott, huge numbers of Achilles tendon ruptures. We know the fluoroquinolones have a huge number of athletes tendon ruptures. So there are drugs that are specifically targeting things. And we don’t know how they work. And it’s still very early days to figuring out how they work. But yeah, there’s There’s definitely lots of lots of really interesting things as far as how these tissues are turning over what their turnover rate is, and what their how dynamic they are.

Because there’s data, there’s really nice data in female soccer players, that shows that the ACL gets bigger over the eight months of the season. As they train, the ACL got bigger. And then what you would assume is since they were all college level athletes, is it in the four months that they took off, that tissue got smaller again. So again, it’s it these are highly dynamic tissues is what we’re learning. And so, so what we’re doing is we’re learning how to support them with the proper loads. Like I just had Camille Heron in here, who’s the world’s greatest ultra marathoner, and she was telling, she had gotten all kinds of bone injuries when she was young runner.

She that made her go into science as a as a college student. And then she did a master’s in bone biology and bone mechanics transduction. And she learned that the the way that a bone worked is it had short periods of load, and it needed good amounts of rest, like six to eight hours. And so the way that she trains is she trains twice a day. Because she knows that by training twice a day, she gets to have the signals that lasts only a short period of time, even when she runs for, say, a hour and a half or two hour run. She knows that her connective tissue only gets maybe a half hour of of an adaptive signal from that two hour run.

But if she does, if she was going to do a four hour run, which is not uncommon for an ultra marathoner, if she breaks it up into two two hour runs, they’re separated by eight hours, she gets to have the stimuli to her bones, tendons and cartilage to have a positive effect, whereas the a different ultra marathoner, who’s doing that as a single session only gets one. And so now what you get is you get you get these differences in how the body is going to respond based on how we’re pairing up the exercise. I know that Brad Lindell had done some work where he had taken military recruits who get tons of stress fractures. And instead of having them run once a day, you had them run half as much as twice a day. Stress fractures go down massively. So just figuring out how the different tissues respond to loading is, is really important for understanding what what exercise training should look like, based on what your injury history is, based on what your capabilities are.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s awesome. And as we wrap up, I know you’ve talked a little bit about possible use of collagen and then certain types of isometric exercise. And I think that it’s interesting, like high level sprinters, you talked about potential hamstring injuries. But if I think about the average gym goer, rarely do ever hear of a muscle tear, it’s almost always a soft tissue related injury. So is there something more for that population they should consider doing related to training? Yeah, so.

Dr. Keith Baar

So again, that’s one of the interesting things that happens because as we as you train, basically your your training, the stiffness of the structures that you’re training based on how you train. So if I do a lot of fast training, my my tenants are gonna get stiffer. To do faster training, I can’t do it against a lot of weights. So that means my muscles not going to get a stimulus for strength, so I’m gonna get a little bit weaker muscle over time. Now I have a stiff tenant and a weak muscle, that’s where I get multiples. Most people don’t do a lot of their training fast. We’ve talked about that already.

So that most of the average people aren’t getting muscle polls, what they’re getting is you’re getting tendon problems and they’re getting kind of these these types of injuries where the muscle is stronger than the tendon and now the the basically when we do a stretch when we do any type of movement, we’re stretching both the tendon and the muscle together. If the muscle is super strong, the muscle doesn’t stretch very far the tendon stretches along way. If the muscle is weaker, and the tenant is stiffer now the muscle has this stretch more. And so what we’re looking to do is balance these two things. So what I would suggest is that in recreationally active individuals, their muscle is stronger than their tenant is stiff, so that when they take a move now this, the tenant is stretching a super long way.

And so that means that the likelihood of an injury is going to be in the tissue, that’s that strains the most. And so that’s where we get a lot of our tenant injuries and other things. And so what we’re doing is what we found, and I’ve got a PhD student, Daniel, Stephan is doing a lot of work with essentially how we should be loading to fix tendon problems, because a lot of times people get, oh, you know, even though people say, Oh, Achilles tendon rupture came out of nowhere, you talk to them, and they’re like, yeah, for a couple of weeks now.

There’s something going on and didn’t feel quite right. And then I took a step and bang point. And that’s the that’s the issue. And so what we’re, what we’re doing is we’re addressing those early, or those tenant empathic areas where I’ve always got pain in my, in the front of my knee, or my Achilles, or in all of these things, or for a lot of throwers, in their, in their elbow, UCL in their elbow, the golfers in their, in the inside the tennis players in the outside. And all we’re doing is we’re doing these 32nd isometrics, where, if you’ve got a lot of tendon based pain, like if you’re super painful in your first few steps, and then it warms up and you’ll get out of it, that’s a good sign that it’s a tendon problem, because the tenant is super stiff first thing in the morning, as you move in a little bit more, it’s going to be a little bit less stiff. And if you have those types of things where you get really, really sore for the first few minutes, or if I go for a run, I can barely move in the first few steps, but then I eventually warm up, those are the things that are telling you that the problem is with your connective tissues, your like your tendons, and that’s where we come in, we use, we use isometrics. The reason we use isometrics is the, that our tissues, our tendons are super dense connective tissue.

And so when we get an injury to it, we get a little bit of damage to it, the load doesn’t go, that load doesn’t stop going through the tissue, what it does is it goes around the damaged area, it’s basically like taking a big rock and throwing it into the river, it doesn’t stop the river, the river just goes around it. And that’s basically what happens to the load that we’re putting onto that tenant, the only time that we’re going to get and that’s what we call stress shielding, because the strong part of the tendons are taking off the low yields the load from going through the weak part of the tenant.

And so what we want to do is we want to fatigue the strong part of the tendon. So that we can get load through the discard part of the tendon. And so the way that we do those, we pull them we hold on the tenant. So we’re using isometric contraction, 30 seconds causes about, you know, 80% of the relaxation that we’re going to see within that tenant. Even if you go out to two minutes, three minutes, it’s only going to go 10 or 20% lower than the tension through the strong part. But as that strong part starts to relax, now the weaker part is actually got more stiffness than the strong part. And so what we get is we get load going through the weaker part. And that load is going to give the cells that signal they need to reorient and start making aligned collagen the way that we want it to be.

And so we’ve had incredible success with this. With a lot of people who you know, who haven’t been able to do their activities that they love to do, they’ll do the 32nd isometrics for a couple of weeks, and they’ll be able to return to play. We’ve done it with professional athletes, we’ve done with all kinds of individuals to help bring them back. And so what we’re doing is we’re doing for 32nd, isometric holds, with two minutes arrest in between. And all we have to do is figure out a way that we can get load through the tissue. So if I have a tendinopathy in my elbow, I’m going to take something and I’m going to rotate it out so that there’s a heavy thing over here and I’m going to hold in that position. So I’ll have tennis players hold a fry pan out with their elbow a little bit bent.

And so now they’re getting lowered through these muscles, which are the external rotators that are going to go through that area where you get tendinopathy. If you’re a baseball player thrower, or you have golfer’s elbow, you just go the opposite way. And now you’re getting loads through the inside, you’re getting that long load hold through the insight, stress relaxation, the damaged part gets that signal to align and to synthesize collagen and a directionally oriented way. And we can repair the collagen.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s awesome. And based on when you talked about with collagen, would you have them do that twice a day then for those four rounds, because you get up the frequency per day. We do it twice a day.

Dr. Keith Baar

So again, it depends on how much it’s limiting you so so if it’s something where you can’t do your activities, then yeah, doing it twice a day is going to get you back faster. And it doesn’t have to be I’d like, you know, the heaviest load, you can pass if you just have to do a load, that’s going to be sufficient to allow relaxation through the strong part get load through the weaker part, the, the older, the denser the scar is, the greater the load, you are going to need to use because that scar is now going to take a lot longer to get that directional signal to if we use a heavier weight, it’s easier for us to get that signal into the to the denser scar. So if we have a really old scar, or really old injury, we’re gonna use a heavier weight to get that load through them.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, that matches some stuff I’ve done in the past with just heavy, heavy ish Essentrics for 1015 20 seconds. And I found just anecdote I can remember where I read the study from that a lot of pendant issues literally within a couple of days started like clearing up, so it was probably maybe the isometric key portion of it, that was a component. Right?

Dr. Keith Baar

So if you did, so that’s the Alfredsson protocol, you Okay, your, your heavy Essentrics, you do heavy concentrix, the heavy component means you go slow, that’s the force velocity relationship. So when we realized that, okay, all of these things that are having a beneficial effect, or are just slow moves, the slowest type of contraction is an isometric contraction, because there’s no movement at all. So by definition is the slowest. And so that’s why we went there. And you put that together with a bunch of other data from from, you know, from horses or from other things where they decrease stiffness. And they saw that the tendons went to looking beautiful again, that told us that what we’re trying to do is decrease that stiffness is important, because that’s how we shield the injury. So we don’t get a lot of tendon opportunities in kids because their tenants aren’t stiff enough yet to shield that little injury. So because they can’t shield the injured area, the injured area gets loaded until we don’t see that scar formation. As we get older and older, we’re going to have stiffer connective tissue, we’re going to be able to shield any injury really, really well. So as I get older, again, I’m going to have to use a heavier weight because the the connective tissue is going to be stiffer at the beginning. So in order for me to overcome that shielding effect, I need to have a bigger load.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

And for isometrics, for people listening, one thing that goofed me up for quite a while I had to unlearn was like strength and conditioning wise, they’re kind of classically taught and isometric is the muscle quote, unquote, not really working, because it’s not moving. But what happens is, I’m like, well go do a wall, sit for two minutes and tell me your quads aren’t doing anything. And it’s the muscle is still contracting, but because there’s play in the soft tissue, the joint does isometric mean to the joint space isn’t changing an angle, but the muscle is still doing work, because it’s pulling on all that soft tissue.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, the muscle has to do a lot more work, because what we normally use our tendons for in our matrix is to have momentum in the movement, and to capitalize on the momentum so that we get stored and returned energy for free. So if you want to make an exercise hard, if you think a push ups easy, that’s great, do a 32nd down 15 Second up, push up, that’s actually gonna use your muscle much more, because when you’re doing a normal push, if you’re storing and returning energy, and all of these connective tissues throughout the system, the result is you get a lot of bounce back, where you don’t have to use your muscle as a motor. If you actually want to really test your muscle, you go slow movements, because now you’re no longer storing and returning energy from the series elastic component, it’s all the muscular component that has to work much harder. And that’s again, as the series elastic component is doing less of the work, we’re gonna get better signals to potentially both the muscle and the tenant.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

And I think that matches, there’s an old study, I think, from Australia, where you had to do a bench press with at least I think it was a six second pause at your chest to try to eliminate that stretch shortening cycling effect, which is a much longer pause and even people doing pause bench press would be doing. Or you can do it from the bottom as like a starting position where now you’re already in that position. And it’s concentric only.

Dr. Keith Baar

Yep. And that’s what we see with a lot of different things that we do with or doing supplementation, or we’re doing training, you’re not going to see a change with a squat jump. But you’re gonna see a change on a counter movement, jump, the counter movement, jump your store name returning energy. So the connective tissue stiffness is really important. On a squat jump, you’re starting from a one position, you’re not storing and returning energy. You’re just trying to produce that rate of force development. And so we don’t see as much of a performance change for a lot of the connective tissue work that we do if we’re only doing a squat jump. And we’re not looking at something like a countermovement.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

ah, Some Well, thank you so much for all your time today, we really appreciate it. And if people want to are in the area and want to enroll in your study, how would they? How would they find you?

Dr. Keith Baar

Yeah, so once everything’s approved on this end from from our IRB, it’s going to be on clinical, clinical trials.gov. Or they can email me at KB AR at UC davis.edu. And that’s just a way that if they’re in the Davis area, and they want to be part of some of our studies, we’re happy to have.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Awesome, and are you looking for any more graduate students if people are interested in that route?

Dr. Keith Baar

So I’ve got a good cohort right now, I’m always interested in in supporting young scientists. So yeah, if there’s exceptional young scientists, I’m always I’m always interested in, in looking at opportunities to increase the number of the individuals that we can get in and get doing outstanding musculoskeletal work, so that we can improve quality of life for for as many people as possible.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Awesome. Well, thank you so much for all your time today. Dr. Barr, we really appreciate it and sharing all your wisdom. Thank you so much.

Dr. Keith Baar

You’re welcome. Thank you for having me.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Thank you. Thank you so much for listening to the podcast today. Really, really appreciate it. A huge thanks to Dr. Keith bar for taking time out of his busy schedule to come on here. To share all the different protocols and different research and everything that he’s done over the years, really, really appreciate him being so open with all the information. If you’ve enjoyed this, and you want to learn more about how to use nutrition and recovery tactics, to maximize body composition and performance, and a complete flexible system.

Check out the Flex Diet Certification. It is open now through Monday, June 13 2022 At midnight, so go to flex diet.com flxdt.com for all the information. If you have any questions, there’ll be a way you can contact me there. I’ll do my best to answer any questions you have. If you’re listening to this outside of that time period, then you can go to flexdiet.com also and get on the waitlist for the next time that it will be open. So thank you so much for listening. Really appreciate it. If you enjoyed this podcast, please leave us a review whatever stars you feel are appropriate. Send it to someone else. And I would appreciate any feedback you have other guests that you would like to see and other information. I will do my best to get other people on the podcast. Thanks again to Dr. Keith bar. Make sure you check out Flex diet.com as it is open now. We will talk to you again and just a few days.

Leave A Comment