On today’s Flex Diet Podcast, I have Dr. Jennifer Heisz, director of the NeuroFit lab at McMaster University. Dr. Heiz recently published a great new book titled “Move the Body, Heal the Mind: Overcome Anxiety, Depression, and Dementia and Improve Focus, Creativity, and Sleep.” We talk about the connection between neurology and exercise and how the body and mind are more connected than we previously realized.

Episode Notes

- Why Dr. Heisz chose to write a book for the general public

- Stigma around mental health

- “Prescribing” exercise for mental health conditions

- Technology for tracking stress

- Stress overload in athletes

- Real threats vs perceived threats

- Exposure therapy

- Pushing beyond your comfort zone

- Violent consistency

- Benefits of exercise to the brain

- ADHD and exercise

- Find Dr. Heiz: research website; jenniferheisz.com, Twitter @jenniferheisz; Instagram @drjenniferheisz

- Move the Body, Heal the Mind: Overcome Anxiety, Depression, and Dementia and Improve Focus, Creativity, and Sleep

The Flex Diet Podcast is brought to you by the Flex Diet Certification. Go to https://flexdiet.com/ for 8 interventions on nutrition and recovery. The course is currently closed, but you can sign up to be notified when the course opens again.

Rock on!

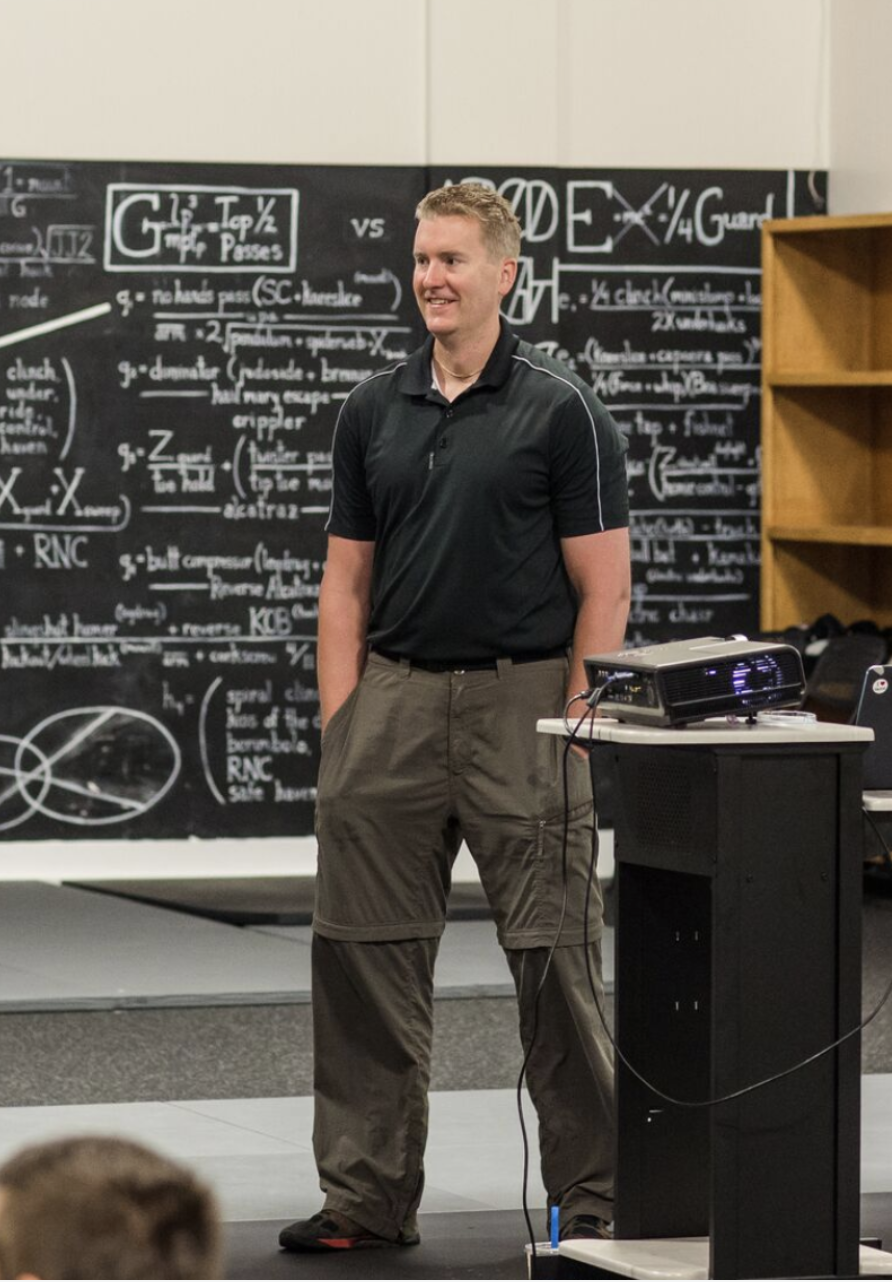

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Hey, what’s going on? Welcome back to the flex diet podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T Nelson. And here we talk about all things to increase performance, better body composition, and do it all without destroying your health and the flexible approach.

Today on the podcast, I’ve got Dr. Jennifer Heiss. She’s the director of the neuro fit lab at McMaster University, great new book that just came out recently called move the body heal the mind, how to overcome anxiety, depression and dementia, and improve focus, creativity and sleep. So we talk all about the connection between neurology and exercise, what are some things you can do if you have anxiety, ADHD, and just fascinating research on how the body and the mind are more connected than what we probably realize.

And research is doing a much better job now of investigating this. So we give some examples there of how exercise can literally change the structure of your brain can change thought patterns help establish just overall, better thinking. So I think when we list a lot of benefits of exercise, myself included, we tend to focus solely on the physical side and for good reason. But there are a ton of mental benefits associated with it also. And this podcast is brought to you by the flex diet certification, go to flexdiet.com.

And you can learn about eight interventions to improve performance and the body comp and health via nutrition and recovery. So in there we talk about one of the interventions is protein. And we’ve got an interview with Dr. Stu Phillips, who works at McMaster University next to Jennifer Heiss, just down the hallway. We also talk about carbohydrates, fats, walking, intermittent fasting, keto sleep, and much more.

So go to flexdiet.com. And you can get on the waitlist for the next time that it opens, in addition to lots of great information on the daily newsletter there. So sit back and enjoy this interview with Dr. Jennifer Heiss author of move the body heal the mind. Welcome back to the flex diet podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T. Nelson. And today we’re here with Dr. Jennifer Heiss who has a brand new book called move the body heal the mind, which is great. I picked it up, and I’ve been really enjoying it so far. So thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Thanks so much for having me.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. So what was your desire to write a book? It’s one thing for you to do research. It’s a whole nother animal to write a research based book for the general population, as I’m sure you’ve probably figured out doing it.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, totally different skills that for sure. But writing books has always been like a lifelong dream of mine. And I’m always interviewing people who’ve written books. Oh, how’d you get into it? Why do you do it? Yeah. And for me, personally, I feel that, you know, as scientists, it’s really important for us to communicate our science to the general public, because they need the knowledge that we have.

And I just happen to have this very personal attachment to exercise and mental health that I think lends itself to a really nice story that gets wrapped around the research and my book. So my own personal struggles, trying to make exercise part of my life, my own challenges with mental health issues around anxiety and OCD. And then finally finding exercise as the medicine that I needed for my mind, which really made a shift in both my research and in my personal life. So before I got into the exercise, neuroscience research we do in the neuro fit lab now, I was just a fundamental neuroscientist studying how the brain represents who we are.

And it all happened in grad school, you know, the stress of the situation really triggered maybe an underlying vulnerability in my brain. And I was reluctant to take medication and fortunately I somehow stumbled i on a whim I borrowed my friend’s rusty, old rode bike and those bike rides soothes my mind and really had a profound impact on both my personal and professional life.

And so I wanted to share all that with people because I think that, especially young people, but also, you know, older people, they, they need to see representation of people who, you know, quote, unquote, look successful, but have mental health issues or have learned to manage their mental health issues at various degrees. And I, especially now, since the onset of the pandemic, things like mental health issues of depression and anxiety, they can really arise in anyone, at any point in life.

And so a lot of people during the pandemic, because the situation was so stressful, they, for the first time in their life, we’re experiencing symptoms of anxiety in the form of, you know, tightness in their chest, it felt like they’re having a heart attack, maybe they go to their cardiologist, and the cardiologist is just like, well, it’s anxiety, that’s what anxiety feels like. But for people who’ve never felt it before, it can be really terrifying. And so sharing stories is really important. So people know, they’re not alone. And then backing those stories up with science, it just, I really saw it as like a really great opportunity to make a meaningful impact on the world.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Ya know, I think sort of mental, like illness or struggles or disease or whatever word you want to associate with it is much more common that I think most people realize, like, and then I work in the fitness space, and even just some of the people I’ve been able to work with who are mostly semi public.

For me looking at them before I got to know him from the outside, I was like, Holy crap, this person does that. They run a gym, they do all this stuff. And then when you get to work with them on a more personal level, you realize, wow, they’ve actually struggled a lot, or they still are struggling with things going on where I think from the outside looking in, it’s more common than what we realize, but the general population or most people, and I didn’t realize this either. If we only view them from the outside, we don’t see what’s really going on. And I think it’s much more common than what we realized because of that.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, well, I’m like physical issues that are very obvious, oft, often obvious, these mental health issues can remain a secret, you know, for a long time, or forever for many people. And for me, that was the case, it remained a secret. And there’s a lot of shame around having issues with your mind, because our whole identities wrapped up there, right. It’s all wrapped up in, in the way we think the way we feel that it’s difficult to dissociate, you know, the biological underpinnings of this dysfunction from who we are as people.

And I think that’s why there’s still so much stigma around, you know, sharing stories or, you know, around mental mental illness, when there really shouldn’t be, it really is just a biological disease disorder that needs medical or, you know, some attention some management in some way.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Do you feel that that’s getting better? My bias thought is, I think we’re almost at the point where it looks like yours, there’s a lot more level of awareness. I’ll pick on guys especially guys seem to be worse about it than women. I know, it’s a broad over generalization. But even in that area, especially in military and other areas, I see that it’s becoming a lot these much better than I’ve ever seen before, which I think is a move in the correct direction.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, well, I guess, when when you have any form of illness, it feels like a weakness, right. And, and especially for men that can be really demoralizing to admit, admit that if, if in your own perception, you wrap that up with weakness, when in fact, it’s not weakness, it’s, it’s biology and biology gone wrong, in this case, that needs correcting.

And so if you just try to avoid it, then it’s not going to get any better or go away. And that can lead to a worsening of the situation when it could have been managed better. So, it the statistics are interesting, because the research shows that females struggle more than men and males in terms of mental health issues, but I think this is just a reporting bias.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I think it was my next question. Is that under reporting on the guy’s probably my guess.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, because if you look at suicide rates, For example, they’re higher in men much higher, I think they’re much higher in men and, and that that, to me is so just so heartbreaking that, that, that it’s, it’s allowed to get to the point where the the situation just feels completely hopeless.

And, and so the hope for me is that we can stop it before then, you know, so that we, we de stigmatize it. It’s not a weakness, it is a dysfunction, and it can be corrected, but it’s difficult to do it alone. And you don’t have to do it alone. I think that’s really important messaging.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I think it’s like anything else, like it’s okay to seek professional advice, right? I mean, I consult with my CPA, I don’t know dick about doing my taxes, I know what I should track. That’s about it. You know, people work with personal trainers, they work with coaches of all types, it’s, I guess, in my mind, it’s not any different if we throw it all the show social stigma, and a mini weakness and that type of thing. It’s a similar idea. And I think that’s starting to become a little bit more accepted now. Yeah, and

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I think that the fitness space is actually a really beautiful place where we can start to intervene. So if, if you know, you have this mental health issue, and you’re, maybe you’re too afraid to talk to your doctor, or maybe you don’t want to see a psychologist or psychiatrist that doesn’t, you can see your coach, you can see your fitness trainer.

And so what we’ve tried to do is in the ACSM, Health and Fitness magazine that is like available for for for coaches and clinicians, is we’ve tried to talk about how how coaches can start prescribing exercise for conditions like depression or anxiety, or you know, just even if one of their clients is overly stressed. So what we find in our research is that, especially with athletes, they’re much more comfortable talking about, you know, being stressed, or being overloaded at work or school than they are about saying things like, I’m anxious, I’m depressed, you know.

So if there are words that you can kind of cue on like, stress is one, it’s such a colloquial word now, but if a client seems to be stressed, then what you can do is you can tweak their exercise program so that you avoid stress overload. So this is a really cool fact about the link between mental stress and physical stress of exercise. So there is only one stress system for all stressors.

And this includes psychological stressors we feel during our day, as well as exercise stressors that we we feel during the workout. And so when you have these psychological stressors in your life, and then you try to layer on top of that exercise stress, sometimes if the stress in your life is too high, it can push you into the the allostatic load stress overload where it’s actually starts to weaken and damage the body rather than strengthening it, which is what you want. And so what we recommend is there’s like a lowering of the intensity, especially when you’re feeling more anxious or stressed out or burnt out from work. Focusing more on duration of the exercise, rather than the intensity can be a really helpful sort of cue.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s awesome. Do you recommend any technology, heart rate variability or heart rate or anything to try to get a handle on stress? And obviously, I’m biased? It’s a loaded question, because I do a lot of heart rate variability work. And what I found over time was the same conversations I would have with people in the past about stress. It was easy for them to kind of run away from that even almost changed the language they were using again, like oh, you know, I just thought I was stressed.

But it wasn’t really that bad. Where if they see a metric on their smartphone, and I can see it, I’m like, hey, what was going on here? It’s It was much harder for them to sort of run away and admit that nothing was going on when you see this trend, going down of a marker of physiologic stress from their body, which I found allowed me to actually have deeper conversations with them, because now they sort of acknowledge the elephant in the room and they can’t run from it and then trying to figure out how do you deal with it?

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I love that idea. And actually, we just started getting into measuring heart rate variability in my lab to Yeah, and it it is a really nice marker of stress and one’s reaction to stressors right where A higher heart rate variability is more healthy and lower is really less healthy and unhelpful. And this, this also underscores this interplay between psychological and physical stressors, right?

And how we can use exercise to tone the stress system to increase our heart rate variability and to strengthen that parasympathetic nervous system so that we’re less reactive to even just everyday stressors in our life. So yeah, I like that idea of using a metric, I guess, are this in your experience, this smartwatch is good at capturing heart rate variability to the point that they could be reliable for such a metric?

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I generally, I would say no, right, because the new Apple One is pretty good, I’d want to see more data on it. The problem is because it’s doing the optical pickup off of the wrist is where most of them are. To get heart rate variability, you have to pick off that arm wave, right so that people are listening within literally a couple of milliseconds, right, because you’re just looking for these really, really tiny changes from one heartbeat to the next. Like the aura ring does it off of the vessel in your fingers. So that one has data showing that it’s pretty accurate.

The downside with that is it’s done laying down during the course of the night. So if your sleep is a little bit different, or you’re a high level endurance athlete, where your resting heart rate is super, super low, right, you’re always kind of in this parasympathetic tone. So these other stressors kind of get washed out a little bit. So I’m still kind of old school where I do the chest strap, first thing in the morning, I use the Isolate out sort of athlete is just isolate, they’ve got several studies that have shown that it’s pretty accurate.

And it’s just the 62nd measurement. So once you get to steady state after a minute or two, just 60 seconds to grab the data point. So it’s not too intrusive. And then that allows you to change position dependent upon their resting heart rate. So vast majority people are going to be fine doing it seated. But I’ve got a couple of higher level endurance athletes where they actually have to do it standing, right to try to get them out of that it’s called parasympathetic saturation, or their parasympathetic tone is so high, the stressors don’t show up, you put them in a standing position, obviously, their heart rate is gonna go up a little bit. But that position is at a constant every day. So when you run the variability analysis, you’re just still looking for changes and it’s more accurate.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I love that, I think that would be really helpful to, to track psychological, the impact of psychological stress in their life, but also training overload, right. So so how we can prevent overload because I think it’s really the amount of stress that people have in their life, their mental health stress, can really actually lead to a stress overload and burnout in athletes.

And I don’t believe that it’s very well understood and respected within, within the sports community that, that the psychological stress has such a big role in that and that coaches and athletes need to tailor their their exercise programs depending on how much life stress they are dealing with at the time. I think this is what what we’ve seen in top Thai and athletes lately, where, you know, highest end gymnasts are not even able to compete in the sport that they’ve trained their whole life to do.

Like Simone Biles, like, like, to me, just I don’t understand, I don’t know the whole situation for her, but I just look at and think, Well, if they were trying to push her in the same physical regime that they had been doing the whole time without considering her mental state. And, of course, she’s gone into stress overload and, and, and when, when you’re in a state like that, not only does it make you not physically able to do the exercises, but mentally to like you’re not able to focus and concentrate and compete at such a high level that you need to, like, especially in these high end sports. It’s not just a physical sport, you know, it’s a mental. It’s a mental sport, too.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. And I would argue that, once you get to that level, it’s probably mostly mental, right? I mean, like, if you look at a Olympics, right, the last couple of weeks before a big event, you’re, you’re probably not getting any better per se on a physical level. But mentally, your job then is just to repeat all the great training that you’ve done, you know, and you think about all the stress that goes into it, it’s four years you’ve been training for it.

Some athletes have only one event, and maybe only one time trial once they’ve qualified, you know, just just the elevation of, of stress is pretty high than that. Like you said, then if you add, you know, something else happens in their life, you know, most have to travel to get there everything else, even with athletes like for doing HRV, I’ve lost track of how many athletes have come back to me because I have an athlete out there little context indicators. So they can put down what was your nutrition?

What was your sleep, and they can put in a little notes. So I tell them, like if anything changes or something weird or even if you don’t think it’s related, just put it in the notes. So that way, if we do see changes in heart rate variability, we can go back and look and see what’s associated. Because like you said, sometimes it is training, sometimes it’s nutrition, sometimes it’s emotional things. And I’ve lost count of how many athletes have come back. They’re like, yeah, man, my HRV was tanking for like two days, and I couldn’t figure it out.

And I look in their notes. And it was some, you know, like, emotional or psychological thing they dealt with, they didn’t think was any issue. And I’m like, Yeah, that was probably yet. Oh, my gosh, that’s so weird. I never thought that, and stuff that you think like, oh, we had an argument, my wife, my dog passed away, you know, things that we would all associate, our, our stressors, especially in athletes, it just seems like it’s hard for them to realize that that will show up in the physical side. Also, it’s like they’re very good at segmenting the two.

But I think even just that level of awareness to be like, oh, yeah, that, you know, can definitely have an impact. And what’s fascinating too, is that some athletes more than others, buddy of mine told the story of pretty high level professional athlete he’s working with came into his facility, he’s driving into the facility to train them. And he sees this athlete show up on ESPN for something that was not very good. He ended up you know, getting arrested, had spent a night in jail, whatever. And so he’s thinking, he’s like, Oh, my God, this athlete is going to be like, destroyed, we’re gonna have to change this whole training comes in does all the HRV analysis, everything’s fine. He’s like, Hey, we’re, you know, this thing that just happens. I don’t care about that. Like, really, we’re like, on national TV for this, or whatever. You know, so it was fascinating to me how that’s completely different from one person to the next. And that question for you is, so an event will happen. But how much of that stress response do you think is also related to the perception of what the person kind of thinks about that event?

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Oh, 100% 100%, related to perception. So this is where mind over matter comes into play and sports psychology comes into play in a big way, is that when we stress is directly related to our amygdala, which is our threat detection center, and that is an evaluation that you’re making on the situation. So you are deciding how big a threat This is, what the threat is, and this is where we can get into a lot of trouble. Because real threats, like, you know, being chased by a lion versus perceived threats, like, oh, I perform terribly, and I’m gonna get cut from the team, they activate the stress system in the same way. And the brain has no way of communicating the nature of that stressor to the body. And so the body reacts in exactly the same way.

And so the the storyline that we’ve created, and the amount of threat associated with that storyline carries a huge role, it can activate the amygdala, which is the threat detection center, and that can send shockwaves into the body. So for example, this player, you know, they’re, they’ve obviously developed some interesting strategies where they’re able to dissociate themselves from, you know, from issues and I mean, that could be good or bad. Maybe that’s leading to some dysfunction in other parts of their life.

And I think it is, you know, it’s good to have a healthy amount of awareness of of, of repercussions of actions. But, yeah, we want to make sure that we are in control of that conversation. And that if so what can happen is then it’s this threat detection in the brain, send shockwaves into the system, sending a stress response there. Then the brain then inter reinterprets that stress response in the body.

And then that can escalate the stress that you’re feeling the threat that it senses, activating it even more and it creates this like vicious cycle where it really can get away from you quickly. And this is where it’s really helpful to have, you know, reframing techniques. So in mind, or just, you know, some self talk, where you come back to the facts, you know, come back to what are the facts, because we can create a story in our mind that gets well away from the facts and is based on a lot of assumptions. And I find a really helpful technique when I’m kind of trapped in my negative thinking is just, Okay, well, what are the facts? What can we really trust and believe, and that is often a really common way to center yourself.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Awesome. Also, related to that, is there a way we can do some movement practice, I’m thinking like, simulation based training, or some people have called it like threat inoculation where you could do a graded, maybe stimulus of some kind and do well, and then sort of just like, exercise graded back up again, to reprogram both the mind and the body.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, yeah. So we call that exposure therapy. And it’s a way to expose you to the thing that you fear or threat that you see as a threat the most, in a safe space, in sort of micro doses, right, so that you, you learn to face it, overcome it and realize you’re still safe. And that helps to train both the mind and the body to be less reactive to that kind of stressor.

So, in the book, I talk about this exactly this for people who have anxiety sensitivity. So people with anxiety sensitivity, you may or may not have an anxiety disorder, but you can still have anxiety sensitivity. And it’s the fear of the body sensations of anxiety. So the heart racing, difficulty breathing. And coincidentally, those are the same symptoms that vigorous exercise induces, right, the heart, heart racing, difficulty breathing. And so people with anxiety sensitivity really don’t like exercising vigorously, they’ll go out of their way to exercise.

And what they need, though, the best medicine for them is to expose themselves to vigorous exercise. And so in the book I talk about, you know, these really short bursts of high intensity exercise for people with anxiety, sensitivity, even just a few seconds, just to activate the system, to feel the heart pounding, and to stop. And then to feel it, come back down to baseline. And repeat that, you know, and keep repeating that until it’s not scary anymore. So you’ve dissociated the physical activation of the body, which isn’t bad, you know, that can get you ready for the performance ready for the task ready for the competition. But it it’s, it’s the thinking around that activation that can derail everything that you want to do, right? So it’s really is trying to convince the mind that this is actually safe, that there is no real threat here. And that we can we can be at this high level of activation and be okay.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s great. And there’s some interesting data you’ve probably seen to about biochemical modifications of those pathways like something and about some of the studies they’ve done with, like maps, a sponsor with MDMA, with PTSD. And there’s some interesting data on using like propranolol and beta blockers with exposure therapy also, any any thoughts on that as similar idea that more of a biochemical component to it?

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah. So I think this is essentially in the way that we can use exercise to start modifying the brain, right. So there, there has been really great evidence to show that, especially for people who’ve experienced trauma, for example, whether it be war veterans, those who have higher levels of this neuropeptide Y seem to be protected from developing things like post traumatic stress disorder, and we can make more neuropeptide Y with exercise. So it seems to be this like resiliency factor. And the really nice thing about neuropeptide Y is that you don’t need to be exercising vigorously to have it have it build up.

It increases even after mild exercise and stays elevated during that acute phase after the exercise. So that, you know, in a way it’s it’s it’s that Mike you know, kind of micro dosing where we’re supplying the A brain with a reset. And I think exercise can really provide that in a safe and like harm free way. The micro dosing with you know, MDMA, it seems very promising.

But there’s also a risk associated with that. And I think that the science is, is really promising. But I would just, there needs to be more. It’s we’re not quite there. Yeah. So if somebody needs something to turn to, I think exercise now is just such a, it’s such a powerful available, safe way to, to induce similar resets in the brain that that we would expect from drugs. In these micro dosing studies, and it’s really interesting that even mindfulness techniques, there’s a lot of interest in mindfulness techniques and meditation techniques, which essentially these like MDMA is essentially enhancing the sensory perceptual experience to bring you back into the present moment, which is essentially what mindfulness training does, and what exercise can do, if you’re focusing on the right thing.

So in the book, I talk about how we can focus on attention to breath even while we’re moving. And that can make the movement more mindful or, or focus on, you know, the experience of of you know, clenching the muscles and moving the body through space. It doesn’t have to be like overly positive, but just focusing on the experience, and in the moment, and I think that based on all the things that the other stuff do to the brain, that that is enough to reset it. And, and so why not try it with exercise as a way to sort of re circuit rewire the brain away from trauma and pain?

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, I mean, my bias is I’m not an expert in these areas at all. But I think the future will be probably a combination of different therapies, and we’ll probably have a better idea of who maybe better response to certain things. And then also, you have to look at from intervention standpoint, what is the potential risk versus reward? Right. I mean, I think exercise has some risks, but they’re relatively low. Most people have access, most people can do it on their own. Yes, getting a coach getting someone to help you can be beneficial, but it’s a much easier access point, I think, for a lot of people. And my guess is that, for long term success, you would have to at some level, incorporate some type of movement, I think, is my gut feeling.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, yeah. And, and I think, you know, when we think about the use of antidepressants, for example, they’re one of the most widely prescribed drugs on the planet. And they’re, they’re prescribed for a host of mood disorders, and but they don’t actually work for a third of the people who take them. And so this one, you know, blanket approach to all forms of mental illness, it has got to change.

And I think that, you know, bringing an exercise into the conversation, bringing other therapies and techniques into the conversation is an important step in, in starting to change that because for those people who don’t respond to antidepressants, actually they respond a lot better to exercise and see clinically significant benefits in improving their mood. So that’s it, I find that really a powerful piece of evidence to suggest you know, how much exercise can change and reset the brain even in cases where they have a clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, my, my thought patterns on that too, is so for example, I’ve had people do a lot of work on the rower concept to rower and they’re trying to hit a certain, let’s say average watt or time. And if you’re doing a pretty all out, it’s miserable. It’s not a lot of fun. But I think the skill set that you learn over time to put up with, you know, live realistically, every part of your body telling you to stop, you know that it’s not painful enough, you’re going to permanently injure yourself, but it’s not fun.

And I think there’s a definitely a transfer in that skill set of being able to focus on the average lots to keep going. And then when you’re done. You definitely feel a lot better after but I do think there’s something to just the ability to focus on that at a very elevated level of stress. And just feel that that skill set under those conditions transfers to other aspects of your life too. And I think we kind of underappreciated how beneficial that could be.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Oh, so much. So part of part of my book includes this journey that I was on from, you know, sedentary to triathlete, and it talks about the whole book. It ends with me completing an Ironman, which is something I never thought would be humanly possible for me. And such a grueling one day event, and just exactly what you’re saying, like, it becomes such a mental game to push, push through the agony and the pain and the, the, you know, the brain telling you, let’s just stop like, a horrible idea.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Why are we doing this, and and it really takes so much resiliency to push yourself beyond your comfort zone. And it’s amazing that the resiliency it takes but you get all that resiliency back and then some and you can start applying that to your life and seeing things that look like obstacles. When you realize I maybe I can do that, you know, you and it, it just builds your confidence not just in the sport, but in life too. And, and I think that that’s just it’s such a powerful gift that you get from exercise.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. And I think that added practice to have the benefits of seeing small wins are like tangible that you can’t talk yourself out of right. In your case, I rode my bike longer. I wrote it faster. I did the swimming. I did. I completed an Ironman, which graduations, that’s extremely difficult to do. And even just people lifting in the gym, Oh, I did two pounds more this week, I did you know, more volume, I did a faster pace.

There’s probably some direction you can move in an intelligent manner. I think being able to see sort of the immediate outcome of your effort. There were a lot of other tasks at work or whatever. It’s very delayed. It’s very fuzzy, I think but to have that confidence of okay, I can do this. Oh, look, I did put in the work, I am seeing these small incremental benefits over time has very powerful. Yeah, but

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I also think that that can actually be a deterrent to a lot of new exercisers. So the especially when you’re new, when you’re new, and you want results now and you’re supposed to look like that it is. And so I I’m trying to shift the conversation for especially for new exercises around, you know, working out not to look good, you know, to lose weight, or to be stronger, but to, to focus on the goal of feeling good, which you get immediately after every single workout. And so we need, we need those quick wins, especially at the beginning.

And research shows that how you feel during those first few workouts predicts whether you’re going to stick with it in the long term. But yes, to your point, those of us who already, you know, have bought into the idea of exercising daily for life. These, these performance gains are super beneficial to keep you motivated. But we can also focus on the mental gains to you know, like I’m sleeping better. I’m thinking more clearly, I’m more productive at work. I’m more creative. I’m. Yeah, it really is. It’s amazing, all the benefits that exercise gives to both the body and the brain.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, I agree. And I think from a neurology standpoint, the more benefits we can kind of stick exercise to it gives people more reasons to do it. But I think it also literally teaches their brain how exercise is medicine and how powerful it is. So I’ve had clients who are newer to exercise, especially more than I worked with general population, the past, like list out some of the benefits, you know, two months into a program than when they started.

And most of the things I’m looking for are not even associated to body composition or whatever. It’s like, oh, I sleep better. I have more energy I can play with my kids now. Oh, my right knee doesn’t hurt. Like trying to get them to realize the transfer of all the benefits they get from exercise. And my hope is, the more that they see that. That’ll hopefully get them to stick with it longer instead of just I was hoping to lose 15 pounds. I’ve only lost five pounds and you know, try to get them out of this kind of myopic view of it.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, I love that. I think it’s so important, especially when the protester is the brain, the brain I heard we don’t have time for this. But if, if the benefit is for the brain, it it does help to you to get over that inertia and get moving.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

And have people I think, realize that it’s fascinating to me how humans are just so hardcore survival wired, right, even things like exercise that even someone who’s been exercising for decades of their life, knows how beneficial it is, they’ll probably still get it done. But even yesterday, like, I have a friggin gym in my garage, I don’t even have to walk 10 feet to get in there to do anything.

And it’s only like a half hour, I really want to go like, you know, and it took me 40 minutes to get into this session to feel like I was doing something productive, and I end up hitting like a PR that I wanted to hit. You know, I’m like, I’ve been doing this shit for 30 years, I still have these conversations myself, you know, I can imagine what it’s like to be new, where you don’t have that experience to fall back on, it’s very easy to have your own brain literally talk you out of doing the thing you want to do.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Exactly. And I hear you on that. It’s so easy. And and yeah, it is a hardwired feature of the brain. It’s a relic of our evolutionary past. And it makes sense. I mean, back in the day, we had to expend a lot of energy to hunt and gather our food. And when we weren’t doing that we needed to conserve energy. And so any voluntary movement was seen as an extravagant expense, and the brain didn’t want you to do it.

So it would it would protest prevent. And so flash forward to now, exercise is a voluntary movement, and the brain sees it as an extravagant expense that it’s trying to prevent you to do. And so fortunately, we’ve evolved some, you know, more logical rational parts of the brain, like the prefrontal cortex that can help, you know, calm down, reassure that lazy brain that you know, resources are plenty. We can do this movement, I like that. This there is science around swishing in sugar, a sugary drink into your mouth.

Yeah. mouthrinse studies on performance. Yeah, the mouthrinse studies how they help to improve performance, and you don’t even have to ingest it, which is really interesting. And I think that’s around convincing the lazy brain that resources are plenty. So it’s like a reminder, okay, there’s sugar sugar is available, we can go do this workout. And and people are able to put in put in more effort. And the other thing to your point about you know, once you start moving, it’s easier to move right and, and so I have this mental health mode of exercise that I evoke, where, if I’m not feeling up for it, I negotiate with myself, it’s like, okay, well, we’ll do the workout.

But if it was supposed to be like a 30 minute jog, we’ll do like a 30 minute walk, run, or take off the intensity, I keep the time in. But it’s amazing that once you start moving, and you start jogging, then you just keep going. And it’s just it reinforces itself. And that’s because once the muscles are contracting and moving, then the neuro chemicals are being released some by the muscles, some within the brain, and they’re just creating that sensation of reward pleasure and feel good.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

What are your thoughts about in that case, I think of it as making exercise more open ended. So I just think lately, we’re for most people, just violent consistency, it’s just doing what you can on a almost day by day basis, and that you’re gonna have some days that are amazing, you’re gonna have some days that are average, and you have some days it just completely suck. You know, but I think the more you make the performance outcome, something that yes, you want to chase something, you do want to hit something, you can see that you’ve made progress. But the paradox at the same time, like you were saying is, can I also make it open ended?

Can I just show up like what I did yesterday, I just show up, whatever I get is what I get, that was the best I could do at that point without, you know, trying to incur any high risk or do anything crazy. And that’s better than what I would have done, which is sit on the couch and do nothing. But I think those compounded over, you know, days to weeks to months to decades is where people make progress. Or I think it’s harder when you’re new because you you remember those really amazing sessions. And you don’t have the experience to know that even in advanced athletes. That’s that’s not daily, right? I think there’s just sort of fantasize ation of all these events, athletes are hitting all these PRs like every day and that’s like so far from the truth. But I think if like you said, just make it more open ended. Do this thing and then see where you end up, I find is easier to get your brain to do it.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Mm hmm, absolutely, this consistency is key, especially over the long term because this, this is a lifelong journey. And the other thing is, if we’re, if we’re trying to go for personal bests every single time, that could be too stressful for the body and actually be counterproductive, right, so, so I love this idea of, you know, just showing up, I work with a coach, and she has, she’s planned my workouts, but she doesn’t talk about, you know, intensity of the or pace, right, at least right now. I’m not training for anything, I’m just, you know, training for life. And most of us are doing that. And and this this idea of training for life is really about consistency and persistency. And, and, and finding a way to move your body a little bit more every day.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

You’re gonna talk a little bit about exercise and like physical structural changes to the brain. So I think that’s one area people may not realize, like the example I think of is a studies have been done with a robic exercise increasing hippocampal volume by was it like more like 50%? Or something? Pretty crazy.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, so the research, yeah, it’s really fascinating around the hippocampus. So there’s been rodents study, so animal models where they, they run on a running wheel, and you can actually count the number of newborn cells within the hippocampus. And the hippocampus is a brain region that’s critical for memory, it’s also what’s damaged by Alzheimer’s disease.

And they, there’s significantly more newborn brain cells that are born in runners brains than non runners brains, it’s just it really is really a magical thing. And this is a relatively new area of research, maybe in the past decade has has really come to life. The first study to demonstrate this was in 9919 99. And before that, people were speculative about whether the the adult brain could actually produce new brain cells.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That was the old thing, were like, Oh, you only have some X number of neurons killed a bunch too bad for you.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I know. But that’s not true. The brain is plastic in the vault, like changing and forever able to produce brain cells throughout the lifespan. And exercise is the most powerful stimulator of that. A really cool new finding is that what why is exercise so powerful? Well, it may have to do with lactic acid or lactate that builds up in the muscles.

So everyone’s familiar with lactic acid associated with that burning sensation. And hydrogen ions, yeah, the higher hydrogen ions creating the acidic environment, right. So when, when lactate, lactate moves through the blood into the brain, it actually goes right to the hippocampus and can produce growth factors, like brain derived neurotrophic factor, which increases the the birth of these newborn brain cells and enhances their functional integration. So it’s really a fascinating new discovery.

And within humans, they’ve shown that exercise, aerobic exercise, even just brisk walking is enough to reverse some of the age related declines in the hippocampus, both in healthy adults but also in people with with Alzheimer’s disease. So it is really fascinating that there’s not just these neural chemical changes that can happen in the brain, but also these structural changes, really changing the gray matter.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

It’s fascinating to me how I mean, for so long, it’s been good, especially in academia, we’ve split off neurology, from muscles is like they’re all in their, like their own little siloed areas. And you just keep learning time and time again, that just so interrelated to each other. And the median thing I think, is just fascinating, right? So it’s a compound that potentially is released from the muscle or a byproduct of the muscle. That’s, as far as we know, not really that active in the muscle, but actually triggers changes in in your brain. So find is just fascinating.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, super fascinating, right? And even other growth factors like Vascular Endothelial factor, that Jeff Yeah, that promotes angiogenesis in the brain. So the birth of new blood vessels which helps carry more oxygenated blood to the prefrontal cortex especially to help enhance for Focus, create concentration, creativity, but also helps ward off things like vascular dementia, which which can can impair our executive functions. Yeah, so super fascinating stuff.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

You’re gonna talk a little bit about ADHD and exercise. I mean, it just seems like there’s, again, I don’t know if the rate of ADHD is going up, or we’re getting better at diagnosing it, or if it’s combination of both, but I’ve seen anecdotally more and more clients with it. And I’ve also noticed over the decade that the ones that just do a lot of volume of I’d say high quality exercise, like most of the time, unless they’ve got some weird stuff going on, like their ADHD symptoms, at least from my side, I’m not trying to diagnose anything appeared to go down. And many times we’ve been able to work with their doc to go off medication almost entirely. But yet, if you talk to most people, exercise and ADHD seems like a little bit of a weird area.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

We study this in my lab, I have a student working on it right now. And exactly what you’re experiencing with your clients is what the research supports. So the benefits of exercise seem to mimic what ADHD drugs do to the brain, increasing dopamine in the prefrontal cortex, increasing blood flow oxygenation. And it’s really amazing, it has a profound effect on improving executive functions, which are, you know, the our higher order cognitive abilities, that, that allow us to focus our attention, ignore distractions.

And this is critical for paying attention in school and at work. And most of the research has actually been done in children showing really strong effects. And the research we’re doing in our lab is on adults, and the benefits seem equally good in adults. One thing that’s really quite fascinating actually, that surprised us, it’s not published yet. So even better, is that people with ADHD, often are comorbid with depression. And this combination of ADHD and depression together really compromises their ability to focus, because concentration is also a symptom of depression. But what seems to be really beneficial is exercise for for this, this subgroup of, of people with ADHD who have high depression.

And I think because it helps not only with their ADHD symptoms, but also with their depression, depression symptoms to have like, a double whammy effect, it’s just super fascinating this link between our ability to pay attention and our mood, and how exercise can really help bolster both to to help people better engage with life.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Well, that’s super fascinating. One of my, I guess, I would say, favorite theory, Bono theories, I like for explaining that as a spectrum is called the entropic brain theory, if you’ve heard of that. And basically what their argument is that all sorts of neurologic diseases should be put on sort of a spectrum. And that has to do with how much sort of variability there is in it.

If you go to the left end of the spectrum, someone who say a schizophrenic, they’re just so variable, like they have a hard time functioning, if you go all the way to kind of the middle area, maybe you’ve got ADHD, maybe you’ve got depression, where you just get stuck, and you have almost no sort of cognitive variability and you feel trapped. And so is interesting, because if it’s true, who knows, right? It’s very hard to show data to support or disprove a lot of those theories.

But if it is true, then that kind of means that exercise may be beneficial, because it may be enhancing different parts and you see overlap between these different diseases, which, historically, they’ve kind of put in their own little silos of like depression here, ADHD here, schizophrenia here. Or it seems like we’re learning that they’re probably more Navy degrees of similar processes. And that exercise and other things can have these kind of pluripotent effects on the kind of the spectrum itself to

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, it’s cool that you bring that up because research that I did in my postdoc was on looking at the the entropy of brain signals. Oh, yeah. So looking at whether there’s an optimal amount of sort of quote unquote, noise that has to be present in the the variability of the brain response. Yeah. So that, that is interesting to think about and And I’m I think that that’s probably true along one dimension at least, where if we just look at the how the neurons are communicating their signal, there needs to be a certain amount of variability.

But then it probably depends on where that deficit in variability is in the brain that leads to different symptoms. Right. Right. So yeah, that’s super cool. I haven’t really thought of that in a long time. But fascinating research on that the brain variability and I guess that would make sense given that you’re interested in heart rate variability, and there’s the the the the alignment the match there.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. My PhD was on fine scale variability differences across physiologic systems. So like, metabolism versus heart rate versus other systems. So I think the introvert brain theory is Roger Carhartt. Harris, I think I could be wrong on that. So awesome. So where can people find out more about the book and pick it up? Find out more about you.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, so the book is called move the body heal the mind and you can buy it anywhere books are sold. You can learn about my research at neuro fit lab.ca Or my backstory and look at some Ironman footage at Jennifer hice H EISZ att.com. Jennifer heist.com. I’m on Twitter at Jennifer hice. And at on Instagram at Dr. Jennifer Heiss.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Awesome. And Stu Phillips. I just say hi.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, we work down the hall from each other. The same facilities? Yeah. Since the pandemic, I haven’t seen him much except just like this over zoom.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah, it is. Definitely weird of, I would imagine it’s even more weird to be in academia now with everything being more virtual too. So yeah. How do you know Stu? Just through exercise fist stuff. I’ve stalked him for years going to conferences and stuff like that.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

So yeah, he’s so awesome. Such a supporter, such a super nice

Dr. Mike T Nelson

guy, a few podcasts with him and always just super nice and gracious with his time. And he’s also very good at explaining things like some researchers are really good at research. But they’re, they’re not the best at explaining this. Yeah.

That too, which is great. So good. Awesome. Well, thank you so much for all your time today. I really appreciate you coming on here. This was great.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Thank you so much for having me. Yeah. Take care. Hi,

Dr. Mike T Nelson

thank you so much for listening to the podcast. Really appreciate it. Big thanks to Jennifer Heiss for coming on to the podcast and sharing all of her wonderful knowledge in her new book. It’s really great. I’m enjoying it. I’m about three fourths of the way through it. And it’s a real nice blend of hardcore research, nice stories, anecdotes, and it was really well done.

So I’m really enjoying it. So I’d highly recommend you check it out. And this podcast is brought to you by the flex diet certification to go to flexdiet.com. And you can learn all about eight interventions to improve body composition and performance using the flexible approach all without destroying your health. So we talked about protein, carbohydrates, fats, fasting, and much more. So go to flex diet.com. You can get on to the waitlist there for the next time that it opens.

Thanks again for listening. Really appreciate it. Any comments on to this, please leave them in iTunes or whatever your favorite player is. And if you enjoyed this and you think someone else may benefit from this content, please forward it over to him. I would greatly appreciate it. Thank you so much. And we will talk to you again next week.

Hey, what’s going on? Welcome back to the flex diet podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T Nelson. And here we talk about all things to increase performance, better body composition, and do it all without destroying your health and the flexible approach.

Today on the podcast, I’ve got Dr. Jennifer Heiss. She’s the director of the neuro fit lab at McMaster University, great new book that just came out recently called move the body heal the mind, how to overcome anxiety, depression and dementia, and improve focus, creativity and sleep. So we talk all about the connection between neurology and exercise, what are some things you can do if you have anxiety, ADHD, and just fascinating research on how the body and the mind are more connected than what we probably realize.

And research is doing a much better job now of investigating this. So we give some examples there of how exercise can literally change the structure of your brain can change thought patterns help establish just overall, better thinking. So I think when we list a lot of benefits of exercise, myself included, we tend to focus solely on the physical side and for good reason. But there are a ton of mental benefits associated with it also. And this podcast is brought to you by the flex diet certification, go to flexdiet.com.

And you can learn about eight interventions to improve performance and the body comp and health via nutrition and recovery. So in there we talk about one of the interventions is protein. And we’ve got an interview with Dr. Stu Phillips, who works at McMaster University next to Jennifer Heiss, just down the hallway. We also talk about carbohydrates, fats, walking, intermittent fasting, keto sleep, and much more.

So go to flexdiet.com. And you can get on the waitlist for the next time that it opens, in addition to lots of great information on the daily newsletter there. So sit back and enjoy this interview with Dr. Jennifer Heiss author of move the body heal the mind. Welcome back to the flex diet podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T. Nelson. And today we’re here with Dr. Jennifer Heiss who has a brand new book called move the body heal the mind, which is great. I picked it up, and I’ve been really enjoying it so far. So thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Thanks so much for having me.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. So what was your desire to write a book? It’s one thing for you to do research. It’s a whole nother animal to write a research based book for the general population, as I’m sure you’ve probably figured out doing it.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, totally different skills that for sure. But writing books has always been like a lifelong dream of mine. And I’m always interviewing people who’ve written books. Oh, how’d you get into it? Why do you do it? Yeah. And for me, personally, I feel that, you know, as scientists, it’s really important for us to communicate our science to the general public, because they need the knowledge that we have.

And I just happen to have this very personal attachment to exercise and mental health that I think lends itself to a really nice story that gets wrapped around the research and my book. So my own personal struggles, trying to make exercise part of my life, my own challenges with mental health issues around anxiety and OCD. And then finally finding exercise as the medicine that I needed for my mind, which really made a shift in both my research and in my personal life. So before I got into the exercise, neuroscience research we do in the neuro fit lab now, I was just a fundamental neuroscientist studying how the brain represents who we are.

And it all happened in grad school, you know, the stress of the situation really triggered maybe an underlying vulnerability in my brain. And I was reluctant to take medication and fortunately I somehow stumbled i on a whim I borrowed my friend’s rusty, old rode bike and those bike rides soothes my mind and really had a profound impact on both my personal and professional life.

And so I wanted to share all that with people because I think that, especially young people, but also, you know, older people, they, they need to see representation of people who, you know, quote, unquote, look successful, but have mental health issues or have learned to manage their mental health issues at various degrees. And I, especially now, since the onset of the pandemic, things like mental health issues of depression and anxiety, they can really arise in anyone, at any point in life.

And so a lot of people during the pandemic, because the situation was so stressful, they, for the first time in their life, we’re experiencing symptoms of anxiety in the form of, you know, tightness in their chest, it felt like they’re having a heart attack, maybe they go to their cardiologist, and the cardiologist is just like, well, it’s anxiety, that’s what anxiety feels like. But for people who’ve never felt it before, it can be really terrifying. And so sharing stories is really important. So people know, they’re not alone. And then backing those stories up with science, it just, I really saw it as like a really great opportunity to make a meaningful impact on the world.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Ya know, I think sort of mental, like illness or struggles or disease or whatever word you want to associate with it is much more common that I think most people realize, like, and then I work in the fitness space, and even just some of the people I’ve been able to work with who are mostly semi public.

For me looking at them before I got to know him from the outside, I was like, Holy crap, this person does that. They run a gym, they do all this stuff. And then when you get to work with them on a more personal level, you realize, wow, they’ve actually struggled a lot, or they still are struggling with things going on where I think from the outside looking in, it’s more common than what we realize, but the general population or most people, and I didn’t realize this either. If we only view them from the outside, we don’t see what’s really going on. And I think it’s much more common than what we realized because of that.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, well, I’m like physical issues that are very obvious, oft, often obvious, these mental health issues can remain a secret, you know, for a long time, or forever for many people. And for me, that was the case, it remained a secret. And there’s a lot of shame around having issues with your mind, because our whole identities wrapped up there, right. It’s all wrapped up in, in the way we think the way we feel that it’s difficult to dissociate, you know, the biological underpinnings of this dysfunction from who we are as people.

And I think that’s why there’s still so much stigma around, you know, sharing stories or, you know, around mental mental illness, when there really shouldn’t be, it really is just a biological disease disorder that needs medical or, you know, some attention some management in some way.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Do you feel that that’s getting better? My bias thought is, I think we’re almost at the point where it looks like yours, there’s a lot more level of awareness. I’ll pick on guys especially guys seem to be worse about it than women. I know, it’s a broad over generalization. But even in that area, especially in military and other areas, I see that it’s becoming a lot these much better than I’ve ever seen before, which I think is a move in the correct direction.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, well, I guess, when when you have any form of illness, it feels like a weakness, right. And, and especially for men that can be really demoralizing to admit, admit that if, if in your own perception, you wrap that up with weakness, when in fact, it’s not weakness, it’s, it’s biology and biology gone wrong, in this case, that needs correcting.

And so if you just try to avoid it, then it’s not going to get any better or go away. And that can lead to a worsening of the situation when it could have been managed better. So, it the statistics are interesting, because the research shows that females struggle more than men and males in terms of mental health issues, but I think this is just a reporting bias.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I think it was my next question. Is that under reporting on the guy’s probably my guess.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, because if you look at suicide rates, For example, they’re higher in men much higher, I think they’re much higher in men and, and that that, to me is so just so heartbreaking that, that, that it’s, it’s allowed to get to the point where the the situation just feels completely hopeless.

And, and so the hope for me is that we can stop it before then, you know, so that we, we de stigmatize it. It’s not a weakness, it is a dysfunction, and it can be corrected, but it’s difficult to do it alone. And you don’t have to do it alone. I think that’s really important messaging.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I think it’s like anything else, like it’s okay to seek professional advice, right? I mean, I consult with my CPA, I don’t know dick about doing my taxes, I know what I should track. That’s about it. You know, people work with personal trainers, they work with coaches of all types, it’s, I guess, in my mind, it’s not any different if we throw it all the show social stigma, and a mini weakness and that type of thing. It’s a similar idea. And I think that’s starting to become a little bit more accepted now. Yeah, and

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I think that the fitness space is actually a really beautiful place where we can start to intervene. So if, if you know, you have this mental health issue, and you’re, maybe you’re too afraid to talk to your doctor, or maybe you don’t want to see a psychologist or psychiatrist that doesn’t, you can see your coach, you can see your fitness trainer.

And so what we’ve tried to do is in the ACSM, Health and Fitness magazine that is like available for for for coaches and clinicians, is we’ve tried to talk about how how coaches can start prescribing exercise for conditions like depression or anxiety, or you know, just even if one of their clients is overly stressed. So what we find in our research is that, especially with athletes, they’re much more comfortable talking about, you know, being stressed, or being overloaded at work or school than they are about saying things like, I’m anxious, I’m depressed, you know.

So if there are words that you can kind of cue on like, stress is one, it’s such a colloquial word now, but if a client seems to be stressed, then what you can do is you can tweak their exercise program so that you avoid stress overload. So this is a really cool fact about the link between mental stress and physical stress of exercise. So there is only one stress system for all stressors.

And this includes psychological stressors we feel during our day, as well as exercise stressors that we we feel during the workout. And so when you have these psychological stressors in your life, and then you try to layer on top of that exercise stress, sometimes if the stress in your life is too high, it can push you into the the allostatic load stress overload where it’s actually starts to weaken and damage the body rather than strengthening it, which is what you want. And so what we recommend is there’s like a lowering of the intensity, especially when you’re feeling more anxious or stressed out or burnt out from work. Focusing more on duration of the exercise, rather than the intensity can be a really helpful sort of cue.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

That’s awesome. Do you recommend any technology, heart rate variability or heart rate or anything to try to get a handle on stress? And obviously, I’m biased? It’s a loaded question, because I do a lot of heart rate variability work. And what I found over time was the same conversations I would have with people in the past about stress. It was easy for them to kind of run away from that even almost changed the language they were using again, like oh, you know, I just thought I was stressed.

But it wasn’t really that bad. Where if they see a metric on their smartphone, and I can see it, I’m like, hey, what was going on here? It’s It was much harder for them to sort of run away and admit that nothing was going on when you see this trend, going down of a marker of physiologic stress from their body, which I found allowed me to actually have deeper conversations with them, because now they sort of acknowledge the elephant in the room and they can’t run from it and then trying to figure out how do you deal with it?

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I love that idea. And actually, we just started getting into measuring heart rate variability in my lab to Yeah, and it it is a really nice marker of stress and one’s reaction to stressors right where A higher heart rate variability is more healthy and lower is really less healthy and unhelpful. And this, this also underscores this interplay between psychological and physical stressors, right?

And how we can use exercise to tone the stress system to increase our heart rate variability and to strengthen that parasympathetic nervous system so that we’re less reactive to even just everyday stressors in our life. So yeah, I like that idea of using a metric, I guess, are this in your experience, this smartwatch is good at capturing heart rate variability to the point that they could be reliable for such a metric?

Dr. Mike T Nelson

I generally, I would say no, right, because the new Apple One is pretty good, I’d want to see more data on it. The problem is because it’s doing the optical pickup off of the wrist is where most of them are. To get heart rate variability, you have to pick off that arm wave, right so that people are listening within literally a couple of milliseconds, right, because you’re just looking for these really, really tiny changes from one heartbeat to the next. Like the aura ring does it off of the vessel in your fingers. So that one has data showing that it’s pretty accurate.

The downside with that is it’s done laying down during the course of the night. So if your sleep is a little bit different, or you’re a high level endurance athlete, where your resting heart rate is super, super low, right, you’re always kind of in this parasympathetic tone. So these other stressors kind of get washed out a little bit. So I’m still kind of old school where I do the chest strap, first thing in the morning, I use the Isolate out sort of athlete is just isolate, they’ve got several studies that have shown that it’s pretty accurate.

And it’s just the 62nd measurement. So once you get to steady state after a minute or two, just 60 seconds to grab the data point. So it’s not too intrusive. And then that allows you to change position dependent upon their resting heart rate. So vast majority people are going to be fine doing it seated. But I’ve got a couple of higher level endurance athletes where they actually have to do it standing, right to try to get them out of that it’s called parasympathetic saturation, or their parasympathetic tone is so high, the stressors don’t show up, you put them in a standing position, obviously, their heart rate is gonna go up a little bit. But that position is at a constant every day. So when you run the variability analysis, you’re just still looking for changes and it’s more accurate.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

I love that, I think that would be really helpful to, to track psychological, the impact of psychological stress in their life, but also training overload, right. So so how we can prevent overload because I think it’s really the amount of stress that people have in their life, their mental health stress, can really actually lead to a stress overload and burnout in athletes.

And I don’t believe that it’s very well understood and respected within, within the sports community that, that the psychological stress has such a big role in that and that coaches and athletes need to tailor their their exercise programs depending on how much life stress they are dealing with at the time. I think this is what what we’ve seen in top Thai and athletes lately, where, you know, highest end gymnasts are not even able to compete in the sport that they’ve trained their whole life to do.

Like Simone Beals, like, like, to me, just I don’t understand, I don’t know the whole situation for her, but I just look at and think, Well, if they were trying to push her in the same physical regime that they had been doing the whole time without considering her mental state. And, of course, she’s gone into stress overload and, and, and when, when you’re in a state like that, not only does it make you not physically able to do the exercises, but mentally to like you’re not able to focus and concentrate and compete at such a high level that you need to, like, especially in these high end sports. It’s not just a physical sport, you know, it’s a mental. It’s a mental sport, too.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Yeah. And I would argue that, once you get to that level, it’s probably mostly mental, right? I mean, like, if you look at a Olympics, right, the last couple of weeks before a big event, you’re, you’re probably not getting any better per se on a physical level. But mentally, your job then is just to repeat all the great training that you’ve done, you know, and you think about all the stress that goes into it, it’s four years you’ve been training for it.

Some athletes have only one event, and maybe only one time trial once they’ve qualified, you know, just just the elevation of, of stress is pretty high than that. Like you said, then if you add, you know, something else happens in their life, you know, most have to travel to get there everything else, even with athletes like for doing HRV, I’ve lost track of how many athletes have come back to me because I have an athlete out there little context indicators. So they can put down what was your nutrition?

What was your sleep, and they can put in a little notes. So I tell them, like if anything changes or something weird or even if you don’t think it’s related, just put it in the notes. So that way, if we do see changes in heart rate variability, we can go back and look and see what’s associated. Because like you said, sometimes it is training, sometimes it’s nutrition, sometimes it’s emotional things. And I’ve lost count of how many athletes have come back. They’re like, yeah, man, my HRV was tanking for like two days, and I couldn’t figure it out.

And I look in their notes. And it was some, you know, like, emotional or psychological thing they dealt with, they didn’t think was any issue. And I’m like, Yeah, that was probably yet. Oh, my gosh, that’s so weird. I never thought that, and stuff that you think like, oh, we had an argument, my wife, my dog passed away, you know, things that we would all associate, our, our stressors, especially in athletes, it just seems like it’s hard for them to realize that that will show up in the physical side. Also, it’s like they’re very good at segmenting the two.

But I think even just that level of awareness to be like, oh, yeah, that, you know, can definitely have an impact. And what’s fascinating too, is that some athletes more than others, buddy of mine told the story of pretty high level professional athlete he’s working with came into his facility, he’s driving into the facility to train them. And he sees this athlete show up on ESPN for something that was not very good. He ended up you know, getting arrested, had spent a night in jail, whatever. And so he’s thinking, he’s like, Oh, my God, this athlete is going to be like, destroyed, we’re gonna have to change this whole training comes in does all the HRV analysis, everything’s fine. He’s like, Hey, we’re, you know, this thing that just happens. I don’t care about that. Like, really, we’re like, on national TV for this, or whatever. You know, so it was fascinating to me how that’s completely different from one person to the next. And that question for you is, so an event will happen. But how much of that stress response do you think is also related to the perception of what the person kind of thinks about that event?

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Oh, 100% 100%, related to perception. So this is where mind over matter comes into play and sports psychology comes into play in a big way, is that when we stress is directly related to our amygdala, which is our threat detection center, and that is an evaluation that you’re making on the situation. So you are deciding how big a threat This is, what the threat is, and this is where we can get into a lot of trouble. Because real threats, like, you know, being chased by a lion versus perceived threats, like, oh, I perform terribly, and I’m gonna get cut from the team, they activate the stress system in the same way. And the brain has no way of communicating the nature of that stressor to the body. And so the body reacts in exactly the same way.

And so the the storyline that we’ve created, and the amount of threat associated with that storyline carries a huge role, it can activate the amygdala, which is the threat detection center, and that can send shockwaves into the body. So for example, this player, you know, they’re, they’ve obviously developed some interesting strategies where they’re able to dissociate themselves from, you know, from issues and I mean, that could be good or bad. Maybe that’s leading to some dysfunction in other parts of their life.

And I think it is, you know, it’s good to have a healthy amount of awareness of of, of repercussions of actions. But, yeah, we want to make sure that we are in control of that conversation. And that if so what can happen is then it’s this threat detection in the brain, send shockwaves into the system, sending a stress response there. Then the brain then inter reinterprets that stress response in the body.

And then that can escalate the stress that you’re feeling the threat that it senses, activating it even more and it creates this like vicious cycle where it really can get away from you quickly. And this is where it’s really helpful to have, you know, reframing techniques. So in mind, or just, you know, some self talk, where you come back to the facts, you know, come back to what are the facts, because we can create a story in our mind that gets well away from the facts and is based on a lot of assumptions. And I find a really helpful technique when I’m kind of trapped in my negative thinking is just, Okay, well, what are the facts? What can we really trust and believe, and that is often a really common way to center yourself.

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Awesome. Also, related to that, is there a way we can do some movement practice, I’m thinking like, simulation based training, or some people have called it like threat inoculation where you could do a graded, maybe stimulus of some kind and do well, and then sort of just like, exercise graded back up again, to reprogram both the mind and the body.

Dr. Jennifer Heisz

Yeah, yeah. So we call that exposure therapy. And it’s a way to expose you to the thing that you fear or threat that you see as a threat the most, in a safe space, in sort of micro doses, right, so that you, you learn to face it, overcome it and realize you’re still safe. And that helps to train both the mind and the body to be less reactive to that kind of stressor.

So, in the book, I talk about this exactly this for people who have anxiety sensitivity. So people with anxiety sensitivity, you may or may not have an anxiety disorder, but you can still have anxiety sensitivity. And it’s the fear of the body sensations of anxiety. So the heart racing, difficulty breathing. And coincidentally, those are the same symptoms that vigorous exercise induces, right, the heart, heart racing, difficulty breathing. And so people with anxiety sensitivity really don’t like exercising vigorously, they’ll go out of their way to exercise.