Today, I’m talking about the 2022 Resistance Exercise Conference held in Bloomington, Minnesota. Plus, I give a primer on the Flex Diet Certification course that will open this June. Find out what to expect and what you’ll learn as you go through the eight interventions outlined in the program.

Episode Notes

-

Overview of the REC Conference (Speakers are named in the audio and listed below)

- Long-term effects of strength training: research and findings

- Good to Go: What the Athlete in All of Us Can Learn from the Strange Science of Recovery by Christine Aschwanden

- Recovery as a business

- Does more recovery work = the ability to train more?

- Top recovery methods

- How to use social media

- Your brand as a business

- Time-efficient strategies for training

- Multi-joint vs. single-joint exercises of hypertrophy

- Minimum effective dose for increases in strength

- Protein around a workout and how beneficial is supplementing protein

- Training to failure and hypertrophy gains

- Hormone hypothesis

- The role of effort with supervision in resistance training: failure vs. non-failure

- Review on variations of exercise

- Mentioned article: Does Lifting Boost Testosterone – at T-Nation

The Flex Diet Podcast is brought to you by the Flex Diet Certification. Go to www.flexdiet.com for 8 interventions on nutrition and recovery. The course will open again in June 2022.

Speaker Information

- Dr. James Fisher

- Dr. Brad Broenfeld (Schoenfeld)

- Dr. Stu Phillips

- Dr. James Steele

- Andrew Coates

- Kristin Rowell

- Luke Carlson

- Discover Strength

- Dr. Pak

- Christie Aschwanden

Rock on!

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Selected References

Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Michalopoulos, N., Fisher, J. P., Keogh, J., Loenneke, J. P., Helms, E., . . . Steele, J. (2021). The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required for 1RM Strength in Powerlifters. Front Sports Act Living, 3, 713655. doi:10.3389/fspor.2021.713655

Angleri, V., Damas, F., Phillips, S. M., Selistre-de-Araujo, H. S., Cornachione, A. S., Stotzer, U. S., . . . Libardi, C. A. (2022). Resistance training variable manipulations are less relevant than intrinsic biology in affecting muscle fiber hypertrophy. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 32(5), 821-832. doi:10.1111/sms.14134

Barbalho, M., Coswig, V. S., Steele, J., Fisher, J. P., Giessing, J., & Gentil, P. (2020). Evidence of a Ceiling Effect for Training Volume in Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength in Trained Men – Less is More? Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 15(2), 268-277. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0914

Behm, D. G., Alizadeh, S., Hadjizedah Anvar, S., Hanlon, C., Ramsay, E., Mahmoud, M. M. I., . . . Steele, J. (2021). Non-local Muscle Fatigue Effects on Muscle Strength, Power, and Endurance in Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med, 51(9), 1893-1907. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01456-3

Burd, N. A., Mitchell, C. J., Churchward-Venne, T. A., & Phillips, S. M. (2012). Bigger weights may not beget bigger muscles: evidence from acute muscle protein synthetic responses after resistance exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 37(3), 551-554. doi:10.1139/h2012-022

Burd, N. A., Moore, D. R., Mitchell, C. J., & Phillips, S. M. (2013). Big claims for big weights but with little evidence. Eur J Appl Physiol, 113(1), 267-268. doi:10.1007/s00421-012-2527-1

Burd, N. A., West, D. W., Staples, A. W., Atherton, P. J., Baker, J. M., Moore, D. R., . . . Phillips, S. M. (2010). Low-load high volume resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis more than high-load low volume resistance exercise in young men. PLoS One, 5(8), e12033. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012033

Carlson, L., Gschneidner, D., Steele, J., & Fisher, J. P. (2022). Short-term supervised virtual training maintains intensity of effort and represents an efficacious alternative to traditional studio-based, supervised strength training. Physiol Behav, 249, 113748. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113748

Farrow, J., Steele, J., Behm, D. G., Skivington, M., & Fisher, J. P. (2021). Lighter-Load Exercise Produces Greater Acute- and Prolonged-Fatigue in Exercised and Non-Exercised Limbs. Res Q Exerc Sport, 92(3), 369-379. doi:10.1080/02701367.2020.1734521

Gomes, G. K., Franco, C. M., Nunes, P. R. P., & Orsatti, F. L. (2019). High-Frequency Resistance Training Is Not More Effective Than Low-Frequency Resistance Training in Increasing Muscle Mass and Strength in Well-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res, 33 Suppl 1, S130-S139. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002559

Grgic, J., Lazinica, B., Mikulic, P., Krieger, J. W., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2017). The effects of short versus long inter-set rest intervals in resistance training on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review. Eur J Sport Sci, 17(8), 983-993. doi:10.1080/17461391.2017.1340524

Grgic, J., Schoenfeld, B. J., Davies, T. B., Lazinica, B., Krieger, J. W., & Pedisic, Z. (2018). Effect of Resistance Training Frequency on Gains in Muscular Strength: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med, 48(5), 1207-1220. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0872-x

Henselmans, M., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2014). The effect of inter-set rest intervals on resistance exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Sports Med, 44(12), 1635-1643. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0228-0

Iversen, V. M., Norum, M., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Fimland, M. S. (2021). No Time to Lift? Designing Time-Efficient Training Programs for Strength and Hypertrophy: A Narrative Review. Sports Med, 51(10), 2079-2095. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01490-1

Lim, C., Nunes, E. A., Currier, B. S., McLeod, J. C., Thomas, A. C. Q., & Phillips, S. M. (2022). An Evidence-based Narrative Review of Mechanisms of Resistance Exercise-induced Human Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002929

McKendry, J., Stokes, T., McLeod, J. C., & Phillips, S. M. (2021). Resistance Exercise, Aging, Disuse, and Muscle Protein Metabolism. Compr Physiol, 11(3), 2249-2278. doi:10.1002/cphy.c200029

Mitchell, C. J., Churchward-Venne, T. A., West, D. W., Burd, N. A., Breen, L., Baker, S. K., & Phillips, S. M. (2012). Resistance exercise load does not determine training-mediated hypertrophic gains in young men. J Appl Physiol (1985), 113(1), 71-77. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00307.2012

Morton, R. W., Oikawa, S. Y., Wavell, C. G., Mazara, N., McGlory, C., Quadrilatero, J., . . . Phillips, S. M. (2016). Neither load nor systemic hormones determine resistance training-mediated hypertrophy or strength gains in resistance-trained young men. J Appl Physiol (1985), 121(1), 129-138. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00154.2016

Morton, R. W., Sonne, M. W., Farias Zuniga, A., Mohammad, I. Y. Z., Jones, A., McGlory, C., . . . Phillips, S. M. (2019). Muscle fibre activation is unaffected by load and repetition duration when resistance exercise is performed to task failure. J Physiol, 597(17), 4601-4613. doi:10.1113/JP278056

Nunes, E. A., Colenso-Semple, L., McKellar, S. R., Yau, T., Ali, M. U., Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D., . . . Phillips, S. M. (2022). Systematic review and meta-analysis of protein intake to support muscle mass and function in healthy adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 13(2), 795-810. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12922

Nunes, J. P., Schoenfeld, B. J., Nakamura, M., Ribeiro, A. S., Cunha, P. M., & Cyrino, E. S. (2020). Does stretch training induce muscle hypertrophy in humans? A review of the literature. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 40(3), 148-156. doi:10.1111/cpf.12622

Phillips, S. M. (2014). A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy. Sports Med, 44 Suppl 1, S71-77. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0152-3

Phillips, S. M., & Van Loon, L. J. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. J Sports Sci, 29 Suppl 1, S29-38. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.619204

Santos, W., Vieira, C. A., Bottaro, M., Nunes, V. A., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Steele, J., . . . Gentil, P. (2021). Resistance Training Performed to Failure or Not to Failure Results in Similar Total Volume, but With Different Fatigue and Discomfort Levels. J Strength Cond Res, 35(5), 1372-1379. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002915

Saric, J., Lisica, D., Orlic, I., Grgic, J., Krieger, J. W., Vuk, S., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2019). Resistance Training Frequencies of 3 and 6 Times Per Week Produce Similar Muscular Adaptations in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res, 33 Suppl 1, S122-S129. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002909

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res, 24(10), 2857-2872. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

Schoenfeld, B. J., Contreras, B., Krieger, J., Grgic, J., Delcastillo, K., Belliard, R., & Alto, A. (2019). Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 51(1), 94-103. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001764

Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Contreras, B., Delcastillo, K., Alto, A., Haun, C., . . . Vigotsky, A. D. (2019). To Flex or Rest: Does Adding No-Load Isometric Actions to the Inter-Set Rest Period in Resistance Training Enhance Muscular Adaptations? A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Front Physiol, 10, 1571. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01571

Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., & Krieger, J. (2019). How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. J Sports Sci, 37(11), 1286-1295. doi:10.1080/02640414.2018.1555906

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017a). The dose-response relationship between resistance training volume and muscle hypertrophy: are there really still any doubts? J Sports Sci, 35(20), 1985-1987. doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1243800

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017b). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci, 35(11), 1073-1082. doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1210197

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D. I., & Krieger, J. W. (2015). Effect of repetition duration during resistance training on muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med, 45(4), 577-585. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0304-0

Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., . . . Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res, 30(7), 1805-1812. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272

Steele, J., Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Carlson, L., Williams, D., Phillips, S., Smith, D., . . . Fisher, J. P. (2021). The Impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Related Public-Health Measures on Training Behaviours of Individuals Previously Participating in Resistance Training: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Sports Med, 51(7), 1561-1580. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01438-5

West, D. W., Burd, N. A., Staples, A. W., & Phillips, S. M. (2010). Human exercise-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy is an intrinsic process. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 42(9), 1371-1375. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2010.05.012

West, D. W., Burd, N. A., Tang, J. E., Moore, D. R., Staples, A. W., Holwerda, A. M., . . . Phillips, S. M. (2010). Elevations in ostensibly anabolic hormones with resistance exercise enhance neither training-induced muscle hypertrophy nor strength of the elbow flexors. J Appl Physiol (1985), 108(1), 60-67. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01147.2009

West, D. W., Cotie, L. M., Mitchell, C. J., Churchward-Venne, T. A., MacDonald, M. J., & Phillips, S. M. (2013). Resistance exercise order does not determine postexercise delivery of testosterone, growth hormone, and IGF-1 to skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 38(2), 220-226. doi:10.1139/apnm-2012-0397

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Hey, what’s going on it’s Dr. Mike T Nelson. And this is the Flex Diet Podcast. We talk about all things to increase strength, performance, lean body mass, and better body composition, all without destroying your health in the process.

Today, we’re going to talk about the REC conference, which was held here in 2022 in Bloomington, Minnesota, the resistance exercise training conference. And before we get into that, just a quick reminder that the flex diet certification opens again, early June 2022.

So right around the corner, get all the information at Flexdiet.com. If you want eight interventions on how to maximize nutrition and recovery, for yourself, or specifically for your clients, then this is what I would recommend. How I set it up is that the eight interventions which covers everything from protein, the carbohydrates to fat, neat exercise, sleep, and more. They’re organized by both physiologic impact, and like client’s ability to change. So that way, you are working on the biggest items to have an impact on clients right away, both on physiology and psychology.

And then within each one of them, we have an ongoing a big picture that talks about the concepts that it’s based on, which is metabolic flexibility and flexible dieting, so that you will know the context of the theories around it. We have an in depth, one hour video on each intervention. I tried to do, I think it turned out pretty good. All the feedbacks been actually much better than I expected.

One hour on all things dietary protein. And if you want to go beyond that with the detailed lectures for each of the eight interventions, we’ve got expert interviews from like Dr. Stu Phillips, who will talk about coming up, he was at the Rec conference got to see him here, again, Jose, Antonio, they are in the protein section. And then we’ve also got expert interviews from Dr. Dan party, Dr. Steven, many others, Dr. Eric Helms, Dr. Mike Ormsby, and a whole bunch of others.

And then what’s different, too, is that we have five exact interventions or action items that you can do and apply to your clients. So not only will you learn how protein fits into the big picture of metabolism, you’ll learn all about protein, you’ll have the ability to listen to to end up lectures from the top researchers about protein. And then you’ll have five specific action items for protein on how to apply them within the system.

Again, that’ll then repeat for each of the eight items. So it is pretty long, it’s over 20 hours long, very complete. And at the end of it, you’ll have a complete system of how to apply nutrition and recovery to your clients. And initially, I set it up so that the if it was one person who was super interested in nutrition for even a large gym of over 100 people, while it would be some effort, you could have a semi guided approach for nutrition for each one of those people.

So check it out at Flexdiet.com get on to the waitlist there, you’ll be the first to be notified. As soon as it opens up. I usually have some fast action, bonus items only for the newsletter also. So go to flex diet.com for all of the details. And of course, any questions you can ask me. And today, as I said, this is a solo cast talking about the rec conference, which was held here in Bloomington, Minnesota, was primarily sponsored by ARX and Discover Strength. So shout out to Luke and Hannah and everyone at Discover Strength who helped organize it. Really, really well done.

It was great to see everybody again, a big thanks for them for putting on the conference. Again I know they’ve done it each year, or at least once or twice. But this is the first time I’ve been able to go to it in Minnesota. I was gonna go to it a few years ago, and just the timing, everything else didn’t quite work out so well. So it started off on Friday, May 13. We had a welcome and everything.

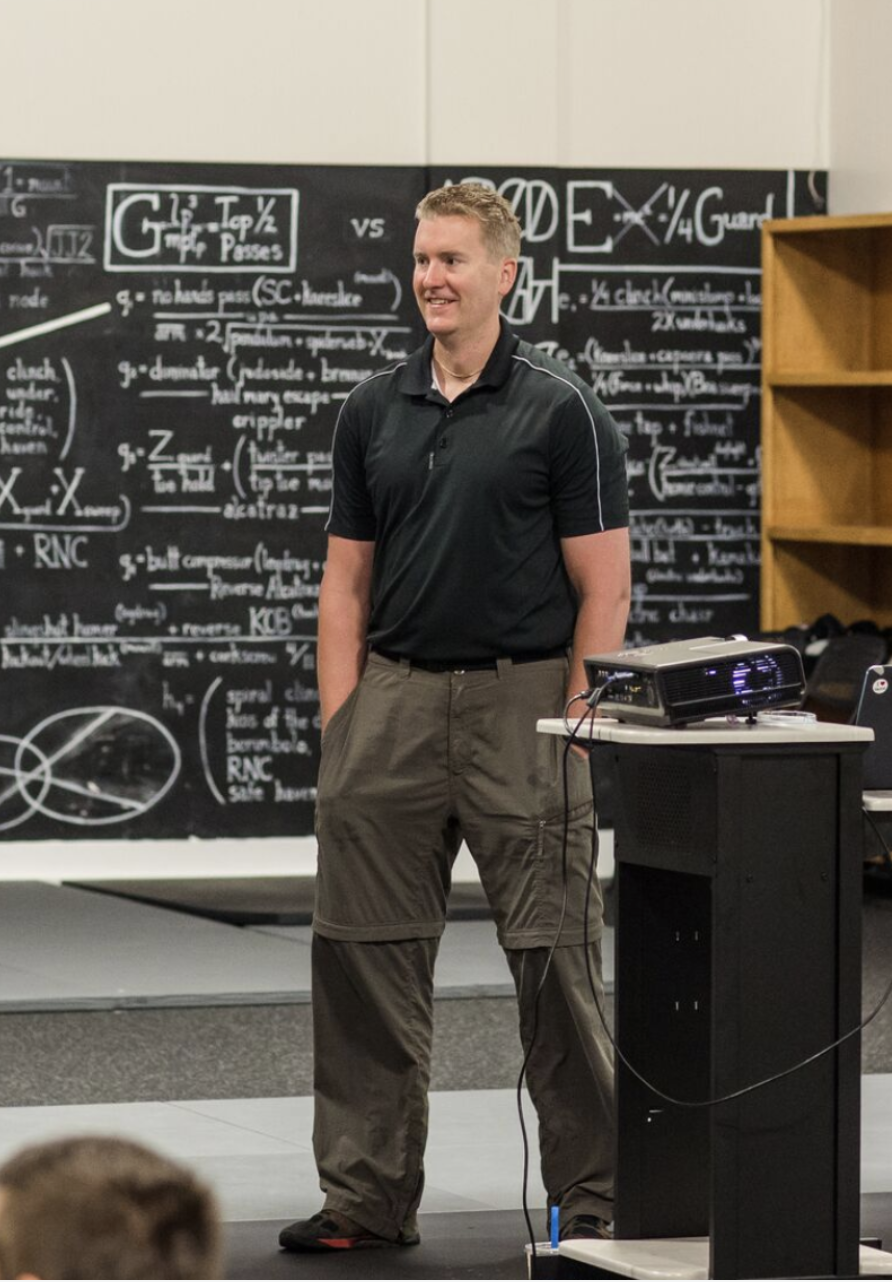

And the keynote presentation that night was my buddy Dr. James Steele. His title was “In it for the long haul, what to expect from resistance training over time.” And it was great to see him again. I think the last time I saw him was is a man that five or seven years ago at the ancestral Health Society or symposium many years ago were both presenting there. And me did a great job of talking about some data on the long term effects with strength training.

What’s interesting now is that as there’s different modalities that are hooked up to kind of computerized systems, and I think we’ll start to see much more kind of data mining from these systems, right, so one of the systems, they showed there was an air rec system. But there are other systems. And what’s cool is that they record all of the sets the reps the time, and you’ve got demographic information for each person, too. So hopefully, it will see I know, he’s working on some other stuff that we can’t talk about yet, trying to publish from some of these large data sets. And granted, it’s not super, super controlled, ie everyone came into the lab and did the exact same thing. But the benefit is you could have, in some cases with some of these datasets, like literally millions of data points.

And most of the sessions are also supervised. And you don’t really have as much human error per se, right, like, self report data from training, you know, can be a real hit or miss. He did a really good job of presenting a basic overview of some statistics, which was great. I think a lot of times this gets glossed over. And one of the key points with that is how do we determine kind of what is sort of a, quote, real effect or not. So I thought he did a great primer on stats for that. So they were looking at some long term data here. And this was from a device called or program called fit 20, where they did one set to failure one time per week for about six sets. And this was literally about 20 minutes. So if you’re looking at kind of what is the minimal kind of effective dose that’s probably near the end of that, and the short version is they did see some long term effects. But it wasn’t massive.

We did see some nice improvements over the short term. But it kind of flattened out over time. Right. So on one hand, you could argue that, well, maybe these people aren’t really getting that much better over time. This data set did go out for several years. The other argument is that most people if they were not doing anything at all, they would be getting worse. Right. So they would definitely be going down in time. So some interesting data.

I think if you polled most trainers, you would say that yeah, wasn’t nearly as quote, impressive as what you thought it might be. But again, we have to keep in mind that this is also an average. And I know he was talking to Brad Schoenfeld, who was there also, we’ll have some stuff from him coming up. And we forget sometimes that research is just showing you general averages, right? So my favorite word with that is, research will kind of give us the direction, but me search, or no one will provide us the answer and air quotes, right, because most people only care about what the program could do for them as an individual. And with that, right, you’re gonna have trainers who are going to work with them, you’re gonna be changing programs. So it’s going to be a little bit different. Well, no, the catchphrase I thought was cool was bending the aging curve. So I liked that I thought that was really good.

And then he talked about a survey data they did during the lockdown period, about long term behaviors. They had over 5000 people complete it. And what they saw was that most did not stop training during lockdown, which is great. Now, these are people who are already training. Most of them did still train at home. This did show to be true, up to about two years later.

What was interesting, though, is that the RPE, again, rating of perceived exertion appeared to go down over those two years, though. So maybe you could argue that people kept training, but the intensity of their training maybe was not quite the same as the non lockdown period.

Yep, so I’ll try to link to some of these studies here. Again, as we go through this, this is meant to be just kind of a rough overview. I’m not going to be able to get into every single detail for it. But when this is published, on either the Facebook’s or the Instagram, if you have any questions, by all means, please post them there. I

‘ll do my best to answer them and to pull the actual research of what it was from. So yeah, so interesting data there. I’m Hopefully that they’re probably publish more in this area. And I think we are seeing a trend of people maybe not training in gyms as much. Does that really hurt the results or not is probably still up for debate on that.

Our next speaker that night was Christine Aschwanden, I hope I pronounced her last name, right, she wrote a great book called The Science of recovery, which actually I read when it first came out. And a couple people had recommended the book to me. And with most, I guess, you could say popular fitness books, I usually don’t get too excited. Unfortunately, I don’t read a lot of them because I get more pissed off reading them than anything else. But I really liked this one, it was actually really good, was very close to the science that had been around in that area. And she made some really great points.

Her talk was just kind of an overview of the book, which I would highly recommend. And one of her main points was that recovery is a verb. Alright, so people are now doing, quote, recovery work. And if you look at recovery as a business, depending upon what modalities you include in there, right in terms of fitness, it’s a really big business.

Now, the hard part with this, is that the quality of a lot of the studies of recovery are generally pretty low. Right? And most of the time, I’ve talked to my buddy Dave bar about this to recovery isn’t even defined with an actual like, definition. Right? So the definition that I like to use for recovery is, if you’re doing your, quote, recovery work, can you come back sooner and have the same level of performance or possibly better? So if you train, let’s say, doing the same training, we’ll say, hypothetically, Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and you do recovery work, Tuesday, Thursday, could you train again, maybe Saturday, that week, and still have the same level of performance? Right?

So if you train back every Monday, and you do recovery work, could you do that training again, sooner? Right. So that gives us a way to kind of define that, if you’re listening to this, and you’re doing more recovery work, in my opinion, then you should be able to do more training, right more volume, keeping the quality of that training high.

Her top recovery ones which kind of overmatched with what I also have here, sleep food, altering your training. And then after that, maybe you get into some some other more fancier ones there, I would throw in adding the cost of everything you’re doing for training, looking at like heart rate variability.

Most of the science she had in there shows that a lot of the recovery stuff, maybe it’s placebo. But again, we don’t have a ton of really great data on that. But she her top ones that she had was sleep, manage stress, and a daily relaxation ritual. And I would agree with all of that, sleep is still going to be number one, you can find other podcasts where I’ve talked about this.

The downside with sleep is once you’ve maximized quality, at some point, you’re going to try to have to find more time to sleep, which can be a challenge for a lot of people managing stress 100% agree with that. Training is a stressor. And your body will perceive a lot of stressors kind of in the same bucket. These could be emotional, could be from your nutrition, your positions, etc.

Again, my bias I like using heart rate variability so that people can manage stress by having the marker to actually measure it. And then daily relaxation ritual I think is also great, let’s could be breathing drills walking outside time and nature etc. She had another great catchphrase too, which she called the data obesity which I really liked. It’s now becoming we’re you know, some clients I do want off consults with have almost too much data. But sometimes the data isn’t really collected in the best way possible. I know devices are trying to toss, heart rate variability into like everything now.

I’ve actually lost one or two contracts by the preliminary meeting, they told me what methods they want to use to capture HRV and I told him that was a stupid idea. And I guess they had already developed a software to measure it that way and I wasn’t hired anymore for that. But um, so some methods are good for HRV or is pretty accurate they follow stayed on that downside is it’s captured lying down. So be careful if your HRV doesn’t move around a lot, if you have a low resting heart rate, I still primarily use Ithlete to measure heart rate variability.

Tony’s published some stuff at HRV for training, so you can use a camera out for that. So there are some valid ways to do it. But just make sure to do your homework on that. It’s a really great talk on recovery. And my last two cents on that is make sure your training is on point first, and then your nutrition, and then worry about recovery. Right. So most of the things you’re going to do for quote, recovery work are pretty not sexy.

Focus on those first, and then you can get a little bit more esoteric. You know, some of the people I get random questions from are about this latest and greatest whiz bang recovery technique. And then you ask them about their training, that’s like, one or two days a week. Alright, so make sure the stimulus that you’re applying to the system is better. First, make sure your nutrition is halfway decent, do some stress management, get more sleep, that’ll take you a super long way.

So next up after that, that was a couple other shorter talks there. My buddy Andrew Coates gave a good talk on how to use social media. And you might be thinking social media, that sounds horrible. Why would I want to be doing that? I don’t like all these Instagram fitness and fluids or people or whatever. But his main message, which I would agree with is that if you have a better information to put out there, which I’d argue a lot of people listening to this podcast do, then it’s kind of your job to disseminate the better information. And that’s the only way everything is gonna get better.

His other point was that many people think all of this has been said before, but it’s okay to reuse some content, or to say, the same ideas and principles just in a slightly different way. I mean, you could argue that almost nothing in the field is entirely brand new. I mean, people have been lifting for hundreds to 1000s of years.

But new concepts, to certain people who haven’t heard it before are going to be beneficial. Right. And the new concept, I have an air quotes. For the longest time, I remember the first time I read the Poliquin principles that come out in 1999 98, someone’s going to correct me on that. And I was like floored, I’m like, Oh, my gosh, you mean there’s something beyond three by 10. I didn’t even know this existed. Right. And so I’m sure trainers a

t that period of time are probably shaking their head. But to me, that was like brand new knowledge. And then I found you know, Bill stars, five by five and Vince Kuranda, was doing an eight by eight. And I was like, Oh my gosh, there’s like tons of other parameters you could do.

And then I know Chad Waterbury was talking about 10 by three. Right. So that book kind of opened me up to, oh, wow, there is a whole bunch of other ways you can do this. And for me at that time, that was novel and kind of earth shattering, right. So not everyone is going to be at the same place where you’re at, people are always going to be entering the field. And disseminating what you feel is good information, I think is very useful. So big thanks to him, make sure to follow him on Instagram, we’ll have where you can follow him in the notes section here.

And it was just super fun to hang out with him all weekend, super great. We got to chat about all stuff, training and writing for different fitness publications. And then of course, lots of chat about good music, of course, which was fun. So then we had day two, which was on Saturday. And that was a good day, Luke Carlson gave a good talk on your brand as a business and inside out approach to building a great brand. So I thought that was very useful. And one of the quotes he had from it is your brand is what you do.

And how your customers feel and culture and core values. Great brands also don’t chase customers, right? So you should have some type of exclusion. Right?

So with Discover Strength he was talking about. They’re very much evidence based. They have a different avatar than other businesses. So there have their three unique properties that it’s built on. And by definition, then you should exclude certain parts of the population, and that’s perfectly fine. Alright, so if you’re listening to this podcast, for example, if you Have you know nothing about nutrition or weight training, probably not the best place to start for you, right?

Because most of the information is going to be more intermediate to advanced. And, again, that’s done on purpose, because that’s the things that I’m more interested in. And I’m looking for the overlap of people that are also interested in that. So good talk on that, really appreciate it.

Next up, we had Mr. Brad Schoenfeld time-efficient trading guidelines and strategies for best practice. Great to see Dr. Brad again, got to hang out with him on the second day for most of the day, which was awesome. And he had a lot of really great references in his talk, I’ll try to post some of them here below. Again, I’m not going to get to all of them.

But again, he made a great, great point that number one is adherence see, right? So whatever you can do and move forward is going to be best. A lot of times when we start talking about time efficient training, we forget that consistency is still going to be number one, right? question was, well, how much volume, what is sort of the minimum effective dose, so volume right for is going to be wait time sets, times reps, and he had something that’s going to be around 10 sets per week, per muscle.

Now, again, some of these studies are kind of more bodybuilding esque, I would say studies, it’s much easier to kind of break them up into sort of body parts, even though there’s gonna be a lot of overlap with that, it’s just easier to do studies on that. And he mentioned that, that doesn’t mean that you have to do that for every single muscle per week, right, you can prioritize some areas, and you’re going to do more volume for that dependent upon your goals. And then you maybe you’re going to do some other stuff, it’s going to be more maintenance, right.

So maybe you’re going to drop to five sets per week on that. So again, these are all just information from research. And we have to take that into account when we do the art of actually creating the training program. So I looked at frequency, what is kind of a minimum dose. And for hypertrophy, he might be able to get by with just one session per week. For strength, again, maybe one session per week. Now again, this is for a minimum dose. And this kind of matches.

Anecdotally what I’ve seen too, if people go off on vacation, and they don’t do anything, probably go backwards a little bit, but you can get by for many weeks to months. And my experience, just doing very little if your goal is just to stay where you’re at. I’ve also noticed the difference between doing very little and nothing is also pretty high.

Meaning if you all of a sudden become a couch potato and do nothing, things will regress pretty fast. And we’ve got some studies looking at microgravity, there’s some other studies using bedrest that have shown that also. But it doesn’t take a whole lot of work to really kind of maintain where you’re at. So if you’ve got a busy period in life, you’ve got a bunch of things going on. Even just one or two sessions a week, we’ll go quite a ways to hold on to some strength and muscle.

He also talked about the hypertrophy zone, which is kind of classically eight to 12 rep range. And this can work for up to 30% of one RM. And in the past, we’ve always said that, oh, if you want hypertrophy, you must train in the eight to 12 rep range. Newer data, I would say. Probably not necessarily true. Dr. Stu Phillips talked about this to Dr. Stu Phillips, Dr. Nick Bird did some of the earliest studies looking at 30% of one RM on leg extensions. And they did go to failure. And they did still see hypertrophy. With that. So for hypertrophy, you’ve got a lot of work and rep ranges you can pick from probably mostly driven by volume.

And if you’re doing less volume going closer to failure. So if you’re really pushed for time, you could make an argument which I would agree with going closer to failure and doing less volume, you can still get some pretty good gains from that. Now again, with strength, it gets a little bit messy, because there’s going to be a nervous system effect.

There’s going to be more of a learning effect with that. The data on that is still kind of up for I’d say debate But you know, if you want to get better at a skill, the more you can practice it stayin fresh, it’s probably going to be to your advantage. That’s your scape goat, you want to practice as often as possible while staying as fresh as possible.

Also talked about multi joint versus single joint and hypertrophy. They did some meta analysis of some studies on that. Again, if you’re equating work between them, it’s probably going to be pretty similar. And you could argue that, you know, multi joint exercises are going to hit more muscles and less time, looking at tempo, varying from one to eight seconds on tempo. So the speed of the rep, they did not see any benefits with that. That was from a meta analysis.

But again, very limited data was only seven studies on that, he did hypothesize that a faster, concentric, maybe better for strength. That’s kind of what I would agree with to that if you want to maximize strength, controlled, eccentric or lowering, and then move the concentric as fast as possible. Obviously, if you’re using a heavy load, fast as possible, it’s still gonna move rather slow.

But the thought process is you want to fire as many of those motor neurons, we’re trying to recruit as much muscle fiber as you can, to move it as fast as possible. I’ve been playing around with some flywheel training since about about November of last year, with an Essentrics device. And what that’s doing is because the flywheel is spinning on both the concentric and the eccentric, when you’re coming up, let’s say from a squat against the flywheel, you’re really trying to move as fast as possible, but because of the mass of the flywheel, you’re gonna move a little bit slower.

And then on the eccentric, the flywheel is still spinning, it’s gonna want to try to yank you back down again. So you’ve got a cool way of playing with speed, even though you’re gonna move at more of what looks like a controlled rate. So one of the main reasons I added that was, as I’m getting older, I don’t do as much speed training per se.

My guess is this is going to be a good way to incorporate it in something that’s very fast. I don’t know how much plyometric work I’m ever really going to do or how much transfer I would see from that, especially for as you get older potential risks involved with that.

So back to Dr. Brad’s talk, rest, he said, but two minutes may be better and complex exercises for both strength and hypertrophy. I know he’s published on in the past, I’ve written a fair amount about that. The old thing of you know, you need to short rest periods of 30 seconds to maximize the hormonal response and all that stuff. That’s pretty well been shown to be bunk. As far as we know right now. Dr. Dan West has published some of that work.

Also from Dr. Stu Phillips lab. So again, quality of work is going to matter. More rest periods is going to allow you to do a higher quality of work. They’re doing, it’s in review right now, study on interest set stretching. So pay attention to browse on social media, I’m sure once that is out that there will be some interesting data on that it was in the lower body using looking at the gastroc and soleus. But since that is under review, that’s not public knowledge yet. So look for that study coming out. Very soon. For more data on that.

Can you get increased range of motion via stretching or lifting, active range of motion will be accomplished from lifting? Do you need to do a general warmup for five to 10 minutes to say cardio beforehand, most of the data right now would say before resistance training that it’s not helpful, but still include a specific warmup, especially if your loads are over 80% of one around.

I would agree with that. I don’t do a lot of general warm ups anymore. If it’s really cold in my garage, I might do a few minutes on the rower. But most of the time, I just don’t even bother to do that. Personally, I do some RPR, reflexive performance reset. And then I just start really light with what the main exercise I’m working on that day. You know, for my training goals, most of the time, it’s going to be a compound lift, even if it’s grip intensive, Axel Saxon bar, etc.

And I just start really light and go up from there. Once I’m warmed up and get into that exercise, yeah, warm ups after that, I think are probably relatively minimal. So you don’t need to spend if you’re really pressed for time. I don’t think you need to spend 10 to 15 minutes on a treadmill or something else to get warm before doing your sessions. I think that’s probably going to be overrated. And then Brad also emphasized the fact that research is just providing us a general guidelines, right.

And the amount of studies will need to really have this to be a lot more defined is going to take a long time, the studies are in progress. But again, once we understand the principles from the studies, we can apply them to how you’re writing specific programs. I think that’s one thing that gets kind of lost and even debated online. People just get into the weeds real fast on specific studies.

And that’s useful. And again, that only applies to that group, that specific study, you’re gonna step back and look at what is all of the data say, in general for that, and that may or may not match what that individual sitting in front of you at that time is trying to do.

Then we had some short rec talks. One of them was from McCollum, Dr. Pack pa K. And he gave one on the minimal effective dose for meaningful increases in strength.

What I liked about this was it was the minimal effective dose for strength, not the maximal dose for maximal gains, right, because a lot of people are looking for what is the minimum to get most of the result. So he talked about what is a meaningful increase, right? So refer to Dr. Fischer and Dr. Steele’s work, they’re looking at some stats. And what I liked about this is that he mentioned the study they did in power lifters. And they looked at a one rep max near a 9.5, RPE.

Right, so very, very high rate of perceived exertion. And or a deadlift where they did that similar and added two more sets at 80% of one RM. And what they found was that, yeah, if you do a little bit more work, it probably going to be beneficial.

But one rep near 9.5, RPE, you can still go quite a ways on that. Right. So they equated it by using stats to what they called about a 30% chance of being meaningful, and quotes. So all that means that if you’re very limited on time, and you can only work up and do one rep near your max, you’re probably still gonna see some benefit from that. jury’s still out if that’s, again, the maximal way to do it, probably not. But if you’re pressed on time, and you’re looking for a minimal dose, again, if you keep the quality of work high, you can go quite a ways on that.

Chris and Rob presented on creatine for women, which I thought was a great talk. And you know, sometimes I forget that things like creatine that I assume have been around for a long time and that everybody knows about that. There’s a lot of new people in the field and even experienced people may not be familiar with it. I’ve started using creatine back in God was it 1996.

We’ve used it mostly odd since then, I’ve taken a few weeks and a few months off here and there. But again, lots of benefits from it. To get the equivalent for creatine, you’d have to eat about one pound of red meat per day on average. So most people are probably not getting enough creatine. Lots of benefits to both health and exercise performance. Common dose is about five grams of creatine monohydrate per day.

Next up, we have Dr. Stu Phillips from McMaster in Canada. Always great to see him again. I know he had to leave a little bit earliest, I didn’t get to chat with him too much. But presented some great data looking at protein, both around a workout. And they did a meta-analysis about do you need to supplement with protein? And if so what would that gain you?

And what they saw from the research was, yes, it is beneficial, but maybe not quite as beneficial as what we thought. I think they had looked at fat free mass went up. I think it was about point three kilograms. I can’t remember the exact time I’ll try to look up the study here and reference it. But again, that was looking at a meta analysis using protein as a supplement. Now keep in mind that some of the data may seem rather unimpressive.

But adding of hypertrophy and protein to your structure in the form of new muscle mass, or lean body mass. I’m kind of using interchangeably even though I know they’re not the same thing. It’s just really darn hard to measure. Right so if you’re looking at the best gains With a Z you can make in a year as someone who’s not brand new to training, I would argue on the data we’ve seen, maybe eight to 10 pounds a year, right. And that’s probably very, very high.

So you’re looking at less than a pound per month in an ideal situation. So we’re talking about very, very small changes over time. From some of the acute studies, the optimal quote unquote, protein after training, you’re gonna need about 8.6 grams of essential amino acids, or 20 grams from egg protein. They’ve also replicated that with 20 grams from whey protein, a new meta analysis from Nunez 2020, if you eat more protein and do not to do resistance training, so they saw protein only if was it beneficial in terms of lean body mass, not really much of an effect. So if you just eat protein and don’t train, are you going to gain a lot of lean body mass? or new to the research right now? Probably not.

However, if you do some type of resistance training, and you add protein, will you add lean body mass? The answer is yes. But again, the results for that are still going to be relatively small. So again, key takeaway, nothing earth shattering, but good to add more data to this external load, definitely going to be needed form of weight training. And yes, if you add more protein, you will see a beneficial effect with that.

So what amounts were they generally talking about? The bottom here is probably about 1.2 grams per kg per day. Right? So if you’re a 220 pound mammal, that’s 100 kg, it’s about 120 grams of protein per day, that’s probably on the minimal side. And that’s still twice the RDA on more of the maximal side, about 1.6 grams per kg per day. So if we use our 100 kg person, again, to under 20 pounds, it’s about 160 grams per day. So when I did the flex diet course, I translated that to the English system, and you’re about about point seven grams per pound.

And that’s, again, is are you going to see a huge effect if you go from 1.2 to 1.6? Nope, it’s going to be relatively small. But it is an effect. So I would argue if you’re really trying to maximize lean body mass and muscle mass, yes, having more protein is going to be beneficial. Do you need to go bonkers on high high amounts of protein? According to the data we have right now? Nope.

That guy mentioned a study they did from Dr. Nick bird back in the day, at momentary failure or perceived exertion, we do find that all motor units are recruited or at least maximally recruited voluntarily. And that can be as low as 30% of our one RM. Alright, so they did a study, they’re comparing 30% versus 80%. And the 30% group did go to momentarily failure or fatigue or whatever word you want to associate with that, when they did see similar hypertrophy games.

There’s been some follow up studies on that too. And that in trained individuals that did see similar hypertrophy gains and a similar strength gains also. There’s some new meta analysis that are out again, that helps support that Dr. Su also talked about the hormone hypothesis gonna link to the article where I have a lot of his research Dr. West research for an article I didn t mag back in the day.

And what we find is that these short bouts of acute hormones released due to exercise don’t really seem to accomplish anything in terms of increasing muscle mass. And we’ve got some very cool data on that. I also talked about they looked at a whole body split 12 weeks, five days per week, and looking at differences in lean body mass from the top to bottom.

And what we saw there was almost as greater than eight fold the difference between people. So in English what this means is that if you’re looking at people who gain lean body mass from the studies, there’s a huge spectrum, even when they tried to control for as many things as possible, which is why you’ll see some people Then the gym make really good gains, doing what appears to be really stupid stuff. But, again, research is helpful to try to figure out for you as an individual, what are the principles that we would need to follow?

I would say the big takeaway from his talk, and also from Brad’s talk, is that you can go much lighter on some exercises, especially if your goal is just hypertrophy, then what most people will program. I know, I’ve changed that, in my own training from talking to Brad and talking to Stu in the past and reading a lot of the research, especially on accessory stuff now, like a tricep press down, I’ll go up to 20 or 30, RM on some of those, right. And if they’re getting close to failure on that, that’s perfectly fine.

I’m probably not going to do that for something like a front squat, right? That’s just pretty miserable. And if you think about how much time under tension there is, and stress and everything else, but I do think for some isolation exercises, having more choice of volumes to play with, is beneficial.

Again, also, if you’ve got clients who’ve got joint issues and other things, you can still get some pretty good results by going lighter than what we probably thought you could in the past. Then we had Dr. James Fisher, the role of effort with supervision within resistance training. So they were trying to look at failure versus non failure. And what they saw was a small to moderate effect size for failure and hypertrophy, but not really a huge difference with strength. Again, this is some more data to show that if your goal is hypertrophy, and depend upon the volume that you’re doing, going closer to failure probably is beneficial. Now, again, that gets a little bit murky, when we’re looking at higher volumes. Right?

So I said, how this has sort of changed my own training, I do go lighter for some accessory stuff, and probably closer to fatigue on them than I would in the past or failure. And then how close do you I’m sorry, at what dose? Do you monitor failure? And they’re looking at this in terms of also supervision.

T here’s a big debate about training to failure. How close should you go? How do you monitor that? Right? So most people in the gym are using an RPE? A lot of the phrasing now has switched to momentary failure. Because we don’t know if it’s really voluntary.

Is it a muscle level. Is it a nervous system level? Is it your brain, central Governor theory, blah, blah, blah. So a lot of the research has tried to accommodate this by using terms such as momentary failure, right? So one of the questions they’re still looking at is, you know, how often should you do that. The other thing that really looking at now is the role of supervision and resistance training. I thought this was pretty interesting that there’s a new kind of a meta analysis, I believe in this area.

And at first glance, it didn’t look like they saw a huge difference. But again, with some of the studies, there’s a lot of variations in them. So they’re looking at some new work in that area. And that’s something he’s probably going to publish more on. So I do think having some supervision will be beneficial. But if we look at all of the data on that, I would say, look for more coming out with that. We did see and report and effect size with strength changes, and supervision.

However, for body comp, they did not see any difference. Now again, you’d have to drill down into the studies to see, I don’t believe they’re controlled for a lot of nutrition in that. So that would not really be that surprising of why you didn’t see huge changes in body composition. looking to see if I’ve got any other last little notes or tidbits here. Yeah, so there was a new review on different variations of exercise. And it looks like more variations might be beneficial up to a point. Right. So we do want to have some variation. But if you have the Old Joe wieder muscle confusion and thing going on all the time, you don’t get enough practice at getting better at those movements, to have them be useful.

So again, we’re back at what is kind of the science and the art in this area. And a study I helped with with Ryan look here, Dr. Ben house and Dr. Tommy wood, where we had people come to Costa Rica for four days in a row and do some pretty brutal training for two hours in Row, and literally had them do the same thing. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, so four days in a row. And what we saw is that, yeah, maybe on accessory stuff, they could still make some good progress. Now, the accessory stuff, there was probably still relatively new to everyone, since most of people were not training there. So the cable and how that is set up might be a little bit new to them. But that one is still in the process of being published. But maybe some early data just show that on the acute sense, we don’t need as much variation as what we thought.

But over the long term, it’s probably going to be beneficial. So how I’ve used this in practice is, someone’s coming back from a layoff. And they’ve got, let’s say, their top three exercises they want to make progress on, I’ll generally program them more frequently, as they’re kind of getting back into the groove. Knowing that they’re going to need some more practice on it.

And I’m not too worried about their performance dropping off, where in the past, I probably would not have upped the frequency quite as high. So for example, for myself, coming back from kiteboarding, I didn’t do a lot of heavy grip or pinch work while I was gone. So I’ve been doing pinch deadlifts using the suction bar, probably three to four times a week, right. And my thought process there is I’m going to get as much frequency as I can with that until I’m back to where my performance was and levels out. And then I’m going to probably pull back a little bit, because I find if I train it more than sometimes two or three times a week, my performance will start to drop off.

But again, everyone has their own individual threshold for that. And we do need to take into account variety, but probably not as much as what I see most people doing. Right. So again, you’re back to kind of what is the art of program design. We want to know things in there week to week, where we can see that you’re making progress. But having a little variety, at some point probably still going to be beneficial.

So there you go. I’ll try to put most of the references or at least some of the ones I can find here at the end. If you have any questions about any of the studies or anything else here, by all means, please post up the questions below.

Huge thanks to all the presenters for taking time and for doing all of the research was awesome to hang out big thanks to Luke and everyone at Discover Strength for organizing the conference. And if you enjoyed this and want more super nerdy information, check out the flex diet certification.

Go to flexdiet.com to get on the waitlist. It will open again for enrollment in early June 2022. If you’re listening to this outside of that time period, you can still get on the waitlist and be notified the next time that it opens. So go to flexdiet.com. Thank you so much for listening to this podcast as always, really, really appreciate it. And we will talk to you next week.

Leave A Comment