I join Zach Bitter on the Human Performance Outliers podcast, where we embark on an exploratory journey through the realms of endurance, resilience, and dietary strategies for peak athletic performance. This episode kicks off with heartfelt thanks to Zach’s listeners and an exciting announcement of a monthly raffle for a free consultation session.

We unpack the mental and physiological impacts of extreme temperature exposure, from cold water immersion to heat acclimation, and their profound effects on athletic performance and muscle protein synthesis. Our discussions illuminate the paradox of discomfort in cold water and the advantages of heat load dumping. Furthermore, we venture into the nuanced debate surrounding ketogenic diets for athletes, questioning whether the high-fat, low-carb regime could unlock greater levels of endurance and whether strategic carbohydrate intake could enhance high-intensity workouts.

Episode Chapters:

- (0:00:03) – Podcast Updates and Road Trip to Austin

- (0:09:37) – Cold Water Immersion Effects on Mind

- (0:22:24) – Heat Load Dumping for Improved Performance

- (0:33:45) – Cold Water Immersion and Muscle Protein Synthesis

- (0:38:59) – Ketogenic Diet Performance and Replication

- (0:49:25) – Performance and Fat Oxidation in Athletes

- (1:02:15) – Performance Benefits of Higher Carbohydrate Intake

- (1:15:24) – Exploring Ketone Esters and Performance Effects

- (1:21:40) – Performance Supplements and Athletes’ Secrets

- (1:33:18) – Gender Gap in Longer Race Performance

- (1:45:51) – Regulations and Technology in Athletics

- (1:51:40) – Shoes’ Impact on Running Performance

- (1:55:51) – Upcoming Certifications and Products

- (2:01:54) – Reviewing Performance Gear

🎧 Listen Here

Rock on!

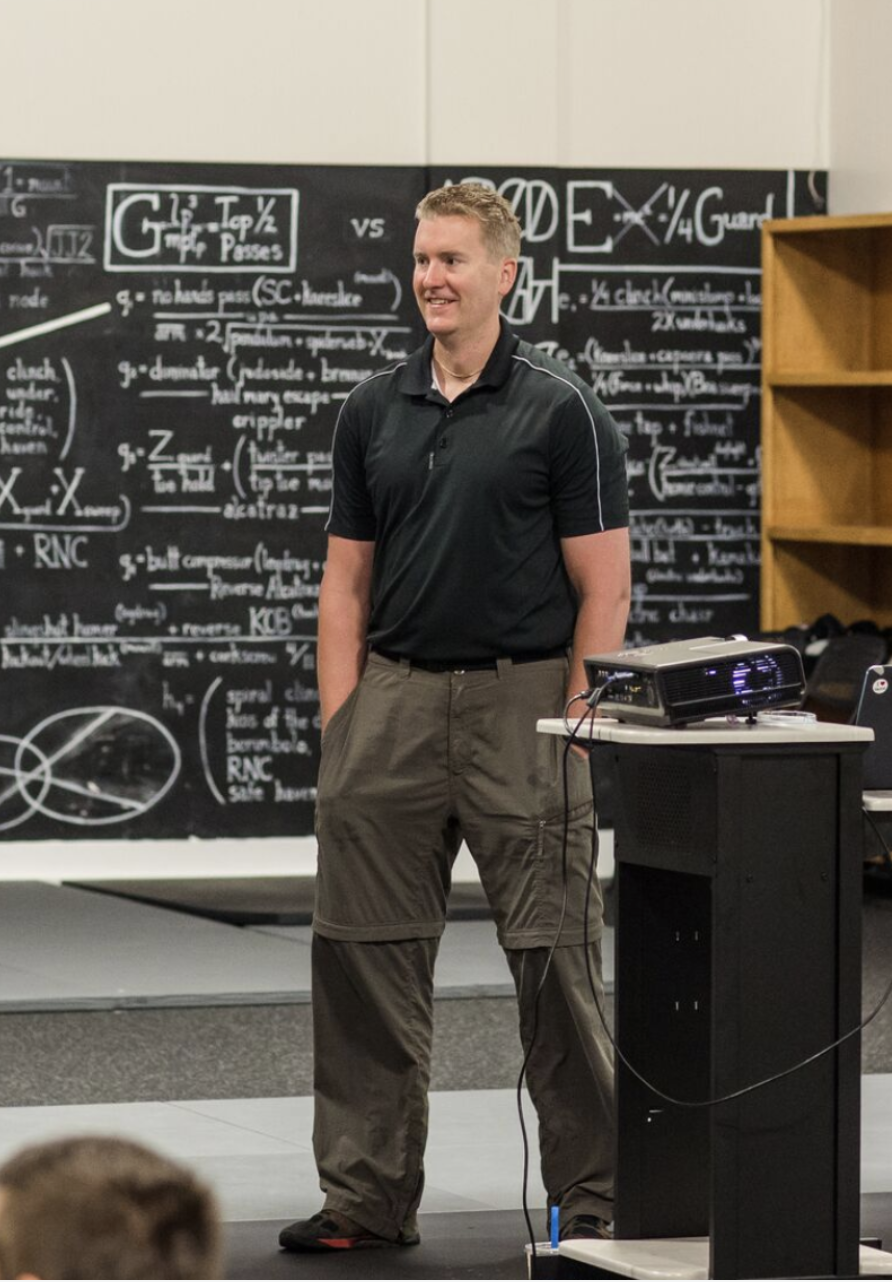

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Episode 380_ Dr. Mike T. Nelson – Metabolic Flexibility

[00:00:00] Thanks for tuning into this episode of the Human Performance Outliers podcast with Zach Bitter. All right, everyone, welcome back to another episode of the Human Performance Outliers podcast. I’m your host, Zach Bitter, and I want to welcome everyone to this episode of the show. As a way to thank the listeners for helping me grow this podcast over the years, I’m going to continue a raffle option for all of you to have a chance to win a free consultation with me.

[00:00:29] So it’s a 30 minute consultation that I will raffle off once per month. All you have to do to enter is share the episodes that you enjoy on whatever platform you find most interesting. The only thing I ask you to do is if it’s a social media channel, make sure you tag me so I see it and can save that and enter the raffle.

[00:00:48] Or if it’s somewhere else that you can’t tag me at, take a screenshot and send that to me at hpopodcast at gmail. com. You can also enter the raffle by writing a show review on your favorite podcast listening platform. So, if you do that, take the screenshot, send it to hbopodcasts at gmail. com and I will enter you in that monthly raffle.

[00:01:13] Also, I’m excited to announce that I launched a new group coaching option. So, to go along with my personalized one on one coaching options and my pre made plans that I have on my website at zachbitter. com, this year I’m starting a group of online endurance runners who want to work with me in a slightly different model.

[00:01:33] So this model is set up so that Whether you’re a beginner or advanced, you can join whether you’re training for something like a 5k or something as far as a 200 plus miler, you are welcome and this setup will help you reach your goals. The way I have it set up is if you subscribe. You will have access to my full catalog of training plans, which range from beginner 5k all the way up to advanced 200 plus miles.

[00:02:01] Along with that plan that you’re going to use, you will have access to a weekly group meeting where you can ask questions about training. You can ask about adjustments to the plan to make it more personalized to you. You can engage with the other group members if you want. Um, we’ll get you all set up and ready to really personalize that plan to make sure that you’re heading in the right direction for your event.

[00:02:23] Also, you will have access to office hours where if you have something you want to ask and you want to just hop in and ask a question, you’ll be given access to that as well. I will be bringing in guest speakers who have a deep understanding of specific topics and things that we’ll use to better your training and recovery process.

[00:02:44] throughout the course of the year, as well as a private forum for all the members to engage with one another, share stories, share training tips, and just how is a lot of the information that we’re all go over on the daily and weekly basis as you’re pursuing your race goals. So if you’re interested in checking that out, just head to my website, exact better.

[00:03:06] com. Go to the coaching tab from there you’ll be directed to the team coaching option and you can sign up for that and get on boarded to join the group. If you’re interested in keeping up with what I’m up to, please give me a follow on some of my socials. Follow me on Instagram at Zach bitter on X, Twitter at Z bitter and check out the brand new HPO podcast handles, which are just at HPO podcast on Instagram and X slash Twitter.

[00:03:36] Of course, all this stuff can be found quite easily on my website, which is the main landing page for everything I do at ZachBitter. com. Before we hop into this episode, I just want to share with you, I’m really excited and fortunate that there’s been some brands that I use. And really believe in that want to support the human performance outliers podcast and are also going to be sharing some discounts and promotions for the listeners throughout the course of the year.

[00:04:04] I have full descriptions of how I use all of these and why I believe in them at the end of the show. So if you’re interested for those details, just stick around after the show and I’ll dive into all of that stuff. But for now, I just want to share with you where you can find them and what their current promotions are right now.

[00:04:21] S fuels offer a low carbohydrate performance and lifestyle product line that matches my approach to low carbohydrate endurance perfectly. If you head to their website at S fuels go longer. com, you can get 15 percent off their products and stay tuned this year because over the course of the year, I am going to be offering up some samples, some free samples of the products that I use throughout the course of the year.

[00:04:48] Janji Apparel makes training gear that I’ve been checking out this winter. They focus on key features of lightweight, breathable, moisture wicking, odor resistant, thermo regulation, super soft and flexible products. These were great for basically any of the running workouts. I’ve done all of them in them and I even use them in the gym now too.

[00:05:09] So if you want to check out some of their stuff, head over to Janji. dot com. That’s j a n j i dot com. And you can get 10 percent off by entering promo code. Bitter one zero element. Electrolytes is my electrolyte of choice. They are offering up a free sample pack for you with your purchase. But if you go to drink l m n t dot com forward slash h p o.

[00:05:35] Right now they are running a seasonal Promotion where they’re doing some chocolate mint chocolate chai and chocolate raspberry as some seasonal flavors I Love using the chocolate mint in the chocolate raspberry in my morning coffee You can also use it in your tea or make some hot chocolate There’s all sorts of different things you can do with this product lineup So head to drink LM and t.

[00:05:59] com forward slash HPO to let them know that you support the show and get that free sample pack with your first purchase Delta G ketone that I’ve been using for a bit over a year now for my training and racing purposes. The reason I chose them is because they have almost all the research backing their formula, 50 plus studies, 20 plus ongoing.

[00:06:19] They had the DARPA grant to design for the special forces. You can also sign up for a free consultation with them to let them know what your lifestyle is like and how that product would maybe fit into it. Right now you can get 20 percent off your order by. Entering promo code Bitter to0@deltagketones.com.

[00:06:39] Mike, welcome to Austin . Yeah, thank you. Welcome. How are you, sir? Good, good. It’s uh, fun to have you coming down this way. You made the long trip from Minnesota by car. We did. We left the end of October. We went down to South Padre Island, so that’s about from Minnesota where we are about. 1, 550 miles. We stopped along the way, so it wasn’t too bad.

[00:07:04] And then I did a conference in Connecticut, so we left from down there, did that, and then we were down in South Padre for about four weeks after that. Yeah. Making our way back home now, slowly. Yeah, slowly but surely. I remember when I lived in Wisconsin during the summer when I was teaching, I would drive out to California sometimes, and it was Kind of a similar distance, but yeah, you get an I 80 and you just basically take that the entire way.

[00:07:27] Oh yeah. There’s not a, there’s some good spots to stop along the way. I think like. Colorado is probably the first, like, if you really like outdoor stuff is a pretty good spot. Um, Utah has some really good spots, but you get some pretty dry spots too, especially heading through, like, Nebraska. Nebraska is the world’s longest state when you go west from the Midwest.

[00:07:47] It’s like, I’m still in Nebraska? Are you kidding me? Yeah, it’s hard to imagine, but Yeah, so you like to do kiteboarding down this way, right? Yeah. So how did that go? It went pretty good, like I, my goal this time was just to try to hit like a, close to a 20 foot jump more consistently. Didn’t quite do that, um, last time before I left I got a 16 foot jump for, I don’t know, it was probably like 130 feet or so.

[00:08:17] Um, but yeah, it was super fun. Got in a fair amount of riding, um, both high winds, not so high winds, uh, attempted to learn how to wing foil a little bit and then attempt to learn how to kite foil and yeah, just got my ass kicked by both of those entirely. So, yeah, speaking of, uh, water, specifically cold water, one topic I wanted to talk to you about, cause I think last time you were on the show.

[00:08:42] We, we, I think we talked about it maybe a little bit or maybe online and, uh, it’s just something where I think between then and now ice baths have gone from something that was sort of like, this is a cool activity that some fringe people were doing that people were aware of to now it seems like everybody and their mom is doing ice baths.

[00:09:00] So I want to talk to you about this because it seems like it’s, it’s like anything that gets popular. You have that big wave of just like. Everyone leaning into maybe one or two studies that say what they wanted to say essentially and then It’ll eventually settle down into like where’s the actual application for something like this And and then with that comes the arguing online of the ice baths will Prevent everything or ice baths are worthless never doing what why do I bother kind of a thing?

[00:09:27] So, um, yeah, what’s your take on ice baths? I’m sure there’s some nuance there in terms of like what you’re trying to get out of it, but it’d be a fun topic to jump into. Yeah, I, so I’ve followed it for a while, and it was like right before COVID happened, I was like, okay, I’m gonna like, you know, take my freezer I had purchased and seal everything and just make my own cold water immersion.

[00:09:50] Just see what happens with it. Mm hmm. And luckily I did that right before that happened So I had it for about three months before I think just got shut down. So I was able to do it every day I wasn’t traveling wasn’t teaching wasn’t going anywhere. I was just at home and What I realized was one freezers aren’t really meant to be Converted to cold water tubs.

[00:10:10] They do work however, the Inside of them is very thin. Mm hmm. So it’s easy to scratch and they can leak a little bit. So Mine now is more filled with silicone to stop that than anything else. And the other part that shocked me was I thought after doing it for quite some time, just like exercise and everything else, we know there’s an adaptation.

[00:10:32] So my thought process being, okay, day one’s gonna suck, you know, month two is probably gonna suck, but a year later, two years later, you know, doing this consistently five, six days a week, it’ll be pretty easy. Like I may not be able to get it cold enough, I may, you know, have to change and get something else or have some water moving through it.

[00:10:49] And when I realized, even after two years of doing it almost every day when I was home, I was traveling a little bit more at the end, right before you get in, there’s still that hesitation of like, shit, what, what am I doing? This is stupid. I don’t want to do this. Like I thought that that would have just kind of completely disappeared, but it, it never did.

[00:11:10] It got easier, but there was still always that hesitation of. This, this sucks. Um, and that’s not even going super cold. That’s even like 42 degrees, 45 degrees, whatever, and it kind of makes sense because it, you know, the little reptilian part of your brain is wired for survival, right? Actually, your whole body is wired for survival.

[00:11:30] And we can kind of modify that with the, you know, professor part of the new, uh, cortex part of the brain, but intrinsically, you’re still wired to think if I stay in cold water, I could literally die, which is true, but it does, um, take quite a period of time in order for that to happen. So I think there’s still that hardwired portion, but what I found was that can be a positive too.

[00:11:56] So what I realized was, and we’ll talk about some of the physiology stuff too. But my biggest takeaway was I think the psychology side of it, I’ve found with myself and with clients was, I think has more positive impact than even the physiology, just because the fact that the main reason I started doing it is, okay, what’s something that’s very hard to do, I could do every day, but it’s not very time consuming as you know, there’s only so many wind gates you can do per day or hard exercise without just being a worthless piece of crap for like two days after.

[00:12:30] But if you really wanted to test yourself, there’s other things you can do like you do some crazy shit But it takes a lot longer time domain in order to do that You know day in and day out and I’m like, oh I bet cold water I bet oh, that’ll that’ll do it. And that’s what I realized is that every day was still hard But you make the decision of okay, this does still suck, but I’m going to go ahead and still do it So you you kind of have that optionality of choosing to do something hard each day Which I do think does transfer to other aspects of your life, whether that’s making a different nutrition choice, going to bed early, taking the stairs, whatever.

[00:13:06] My guess is that I think that skill set does transfer to other aspects of your life. Mm hmm. Yeah, that, I love that explanation because I can relate to it. The way I describe it is if you do like like relatively short dips in the, in the ice bath, like less than three minutes around that timeframe. What I find is it’s like, it trains my mind the same way that I need to train it for like a short interval session.

[00:13:30] So if I’m doing just a classic VO two max, something like let’s just say five by three minutes or six by three minutes or something like that, there is this like ebb and flow of a workout like that where the first one is almost always worse than the second one because you have to like just. Your body into it doesn’t matter if you do strides.

[00:13:49] Well, it does, but it, but it’s like that first one has always got that like relative difficulty that you have to kind of like. normalize. And then you kind of get cruising and then it’s like, then it’s just a balance of finding that spot where, okay, I’ve done enough of these now where I’m going to get an adaptation if I repeat this process enough.

[00:14:06] But I didn’t go so far that I wrung myself dry and now I can’t do another workout for a week. So then it’s just kind of that finding that balance. But you can’t do that many of those types of workouts. So it is something and you may, you may just be dosing them at like certain points of your training cycle versus every week year round, but I can do the ice bath every day and get that same kind of mind process of like this sucks.

[00:14:29] It sucks. It sucks. Oh, maybe it’s not too bad. Okay, I’m settled in. I can do this. So that same kind of doubt Overcome by confidence and then just focus. There’s like that same repetition and I find it to be very useful from that purpose for those purposes. So yeah, it sounds like that’s kind of what you were angling out with it though too.

[00:14:49] Yeah. And then, I mean, I have a course that’s a physiologic flexibility certification. So one of the aspects is how to make yourself more resilient and more robust. And so one of the four pillars is temperature. So with cold, the little term I coined is a stress lesson. So L E S S E N. So when you get in, can you take a known stressor because you know about how long you’re going to be in, you know, what, you know, the size of the tub, it’s water and you know the temperature so you can be very precise with the dosing and then the goal then is not necessarily to get hyper aggressive with overload per se, but can you get in and can you lessen that stressor faster, right?

[00:15:27] So like all the stuff everybody talks about, can you get control of your breathing? Can you Try to get more parasympathetic. Can you get into a calm state? Can you do all that stuff sooner and make that process easier? And then once you get good at that Then I think you can drop the temperature go a little bit longer that type of thing So you’re taking a known stressor, but you’re not looking so much for overload.

[00:15:49] You’re looking for can I make it more efficient? To my body, because that’s, I think, a skill set, especially for like what you do and a lot of other athletes do, I think that skill set is transferable, right? If you’re going to go on, you have to run a certain pace. You have to do a certain thing. The weather is this.

[00:16:05] A lot of stuff is fixed. You’re left with okay. Can I still hit that performance mark? But can I make it easier on my body? Can I look for those efficiency gains? And that’s I think harder to get at with other aspects of training, or I think that’s something like in an ice bath, you can practice very easily and you know, whether you’re doing it or not.

[00:16:27] Like if you get in and you’re freaking the fuck out for like 30 seconds, and then the next day you get in and you only freak out for 20 seconds and then 10 seconds, like you can see that progression very, very fast. Yeah. Yeah. It’s really interesting. What about like duration? I want to say. When I go online, I just look at just kind of the back and forth and the research and stuff like that.

[00:16:48] It seems like the research points towards it being problematic if someone says, say does like a really, like a, like a strength session, strength work. Like let’s say you go to the gym and you do like squats or deadlifts and hop in the ice bath. It seems like there’s evidence that suggests that’s maybe not optimal versus what maybe the athlete anecdote would suggest, which is After a hard workout, I jump in the ice tub and I feel better.

[00:17:10] What is it, what do we know about that side of things? Yeah, so if you look at purely performance, then we’ll talk a little bit about hypertrophy because it’s a separate topic. I’d say the performance data on it is pretty damn split. Like I spent a ton of time going through all the research for years trying to figure out like, okay, can we give some solid recommendations that are repeatable by the research?

[00:17:35] Not really. The only thing I came up with is that if you are an athlete and you are in the season, the sort of the paradigm that I use then is the goal is not. necessarily adaptation. It’s more recovery. It’s, you know, you have a game tomorrow or the next day or every Sunday or whatever your timeframe is, you’re just trying to make it through the season.

[00:17:57] And yes, you want to hold on to some adaptations by all means. But your biggest thing is I need to be recovered because it doesn’t matter what happens. If I’m in the NFL, I’ve got a game, let’s say Sunday at noon, or I’ve got a big race coming up or whatever. So the goal then is just get to the next thing.

[00:18:14] Yeah. And I think in that context, you will trade a little bit of lessening the adaptations or maybe even taking away from it a little bit if you feel better and you can perform again. The next time, uh, most high level athletes, I would say, find it beneficial, even though that’s anecdotal. Um, you go to a lot of, you know, professional places.

[00:18:34] Like if you watch, um, the Netflix series, the quarterbacks, obviously from Minnesota. So big Kirk cousins fan, right? They show them doing a lot of cold water, that kind of stuff. Um, but the research on it is very split. Like you’ll find some stuff with mixed martial athletes, some soccer players showing that there was benefits.

[00:18:51] Um, but sometimes it was only in vertical jump and sometimes it was only in speed and power, and sometimes it was only one particular exercise. It’s just really split. And the hard part too, is that there isn’t a standardized necessarily dosing procedure either. So they’re all using potentially cold water immersion, maybe up to the neck, maybe just lower body.

[00:19:11] They may have water flowing or it may be static. They have different times, they have different temperatures, they have different timing. Was it done immediately after training, or was it done maybe before training, or was it done in the evening, or different times, that type of thing. What we do know from the research that is very reliable, we do see big changes in dopamine and norepinephrine.

[00:19:31] Uh, that’s been pretty well confirmed, both anecdotal and actual research. So most people do feel a lot better once they’re done. And even if that equates to them performing better for an in season athlete, Cool. I’ll take that like all day. And the intervention is like what, five minutes or something like that.

[00:19:50] Great. As long as you warm up again, before you perform your task or your, uh, your sport, you’re probably fine. So I would say it’s pretty, pretty split on the performance side, um, for strength, speed, and power. If you look at more aerobic adaptations, it’s even, I’d say more up in the air. And I would say, if anything, there’s some meta analyses showing that.

[00:20:12] For aerobic adaptations, it might be a benefit, although the effect size was pretty damn small. Um, the modulators of it, how that happens, we’re not really sure. Um, and also the confounding, the big confounding factor in that too is if you read the studies, were they doing it outside in a hot environment?

[00:20:32] Because what I played with in Minnesota, surprisingly, does get pretty warm in the summer. I would do some aerobic stuff and then I would use the cold water immersion as a way to just dump the heat load off my body and then come back again and do another effect of doing some high intensity intervals on the rower.

[00:20:50] And what I found by doing that is I could sustain much higher levels of performance over time. Now, I’m not getting the heat adaptation if I was going to have to perform in a hot climate, which I don’t necessarily have to. So there is a trade off with that. Um, so I wonder about some of the studies looking at endurance performance if they did it outside and it’s a warm environment, obviously your exercise and your heat is elevated is part of that.

[00:21:14] Just dumping that heat load so that you can get back to homeostasis faster. And maybe that’s the mode of recovery. Maybe it’s molecular majors. Pbc one alpha. I don’t know. There’s just even more Variables to play around with it. Just kind of a boring non answer for people who are listening. Yeah. I mean, the, the debate continues, I guess.

[00:21:36] The, the thing that you mentioned that I do find really interesting was, uh, just the, the intra interval dosing of it because living here, we’ve been through two summers in Austin now coming from Phoenix. So like we came from a super hot place to another hot summer. Biggest difference is dry heat to very humid heat.

[00:21:53] So the thing that I sort of relearned because growing up in Wisconsin, we had humid summers, not quite as humid as here, but humid enough is if I’m doing an interval session, like usually like in a dry climate, even if it’s relatively hot, I’ll notice like, Oh yeah, I get pretty good heart rate recovery between right in the humidity of evaporation.

[00:22:12] You can dump that heat load. Yeah. Yeah. You cannot dump it. No. So you’re doing like an interval session. I’m like, Wow, my recovery heart rate is still at like threshold. Like, it’s pretty insane. But if I could just like, yeah, dump that heat load like you mentioned in between interval sessions, I could probably get a little bit higher quality or maybe Eek out an extra interval without any extra cost.

[00:22:33] And then over the course of say an eight week speed or development phase, one extra interval, each one of those workouts is essentially an old mother workout plus. So I think I didn’t try it at all this summer, but I’m probably going to have a setup next summer where I can play around with that a little more specifically.

[00:22:50] So I may try to. Try to play around with that and just see what it shows up in my own kind of end of one data, I guess, but it is an interesting, interesting takeaway. Yeah. And I’d be super curious what you find. I mean, again, I have very limited data on this, but how I would set up the plans is the session would be repeat as much high quality work as you possibly can, um, which I think applies to both speed and power and, uh, endurance athletes.

[00:23:14] So I remember a side note, uh, doing some work with Cal Deets University of Minnesota. And I was helping him write an article, and he has this huge whiteboard in his office. I’ve known Kyle for like 15 years. It’s 40 minutes of me just sitting there, him drawing all this stuff on this whiteboard. And I’m thinking, oh my god, like how the hell am I going to write an article about this that makes, makes sense?

[00:23:34] And so after he finishes all this, I just looked at him and I’m like, okay, so you’re saying do higher quality work first and then add quantity. He kind of pauses. He’s like, yeah. So I think with. The ability to dump a heat load, you can get higher quality work in. Like you said, you probably can get another round of intervals in which over time for, you know, intermediate to advanced athlete is beneficial.

[00:23:59] And then if you know, you have to perform in a hot and humid climate leading up to that, I would take at least probably about most of the literature would say two weeks to actually do specific heat acclimation at that point, because you’re probably not going to eke out a lot of performance gains, you know, those one or two weeks before the race.

[00:24:18] However, you can definitely get a lot more heat adapted during that time. And as you know from experience, if you’re not heat adapted and you go to those types of climates, it sucks even more than what it already sucks. Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, the nice thing about heat adaptation, it is pretty quick. And most of the protocols are like three 20 minute sessions per week after a workout for I think was like three or four weeks maybe.

[00:24:42] And you pretty much got all the All the value you’re going to get out of that. And the nice thing about ultra marathon running is I’ll do a speed work development phase much earlier in the plan. Then I get to long run development or ultra specific long run development. In which case I’m not nearly as worried about, you know, controlling that variable, especially if it is a hot weather race.

[00:25:01] I just did a race in Phoenix in October and it was plenty hot, even though, I mean, it was a cool year and it was still well into the eighties. So it’s like direct sunlight. So yeah. So this summer training in the humidity, like outside of speed work, I was actually kind of like looking forward to it to the, to the degree that it was like, okay, this is going to be what I’m dealing with.

[00:25:19] Probably actually probably worse than what I’ll be dealing with on race day. So. Let’s normalize that a little bit. And since it’s lower intensity for longer in development, it’s just not as much of a problem from an overheating standpoint where I’m losing quality of the workout session. Cause I have to pull back due to overheating.

[00:25:34] Yeah. And the heat adaptation is it’s one of those things that’s been around forever, but it’s surprisingly how some high level athletes I consult with, like they kind of forget about it, which to me is kind of shocking. Um, and again, it’s. It’s one of those things that if you’re not taking into account, it can definitely be to your detriment.

[00:25:54] And like you said, the research on it, you know, one to two weeks, you can get two weeks, you can get a lot of adaptation. If you’re at elite level three to four, probably somewhere in there, you’re probably going to be pretty good. So it’s not something you have to spend years developing. It’s something you can add in within a few weeks out and, you know, see some pretty good benefits from it.

[00:26:12] Yeah. The problem is I’m guessing you lose it pretty quick too. You exactly, you lose it about as fast as you gain it. Yeah. That’s the thing. So. Some athletes, if they have, so one of the athletes I was working with, they have a big event coming up. I can’t say what it is, but big event coming up, and then three weeks later, they have a bigger event after that.

[00:26:31] So it’s a qualifying event. If they make it, then they’ve got a bigger race after that. Um, so we just said, okay, after that, you’re going to have to kind of take a little bit of a deload. You need to qualify first. That’s obviously the biggest thing. Hoping you make that then you can use things like sauna and other things that are more passive recovery To kind of hold some of those heat adaptations without having to train You know necessarily in the environment and add a ton of mileage and a ton of stress To your physiology so you can kind of take some of those things and kind of prolong them for a period of time But you’re correct that if you don’t have any exposure to heat at all like Yeah.

[00:27:09] Yeah. So all summer long, it just takes two cold winter, wintry fall weeks when you train in the heat in the summer. It feels like that’s not fair. It feels like you should earn a longer level of heat adaptation. Although if you’re going to be training in the cool after that, you probably want to lose it as long as you’re not competing in it because you don’t want to be.

[00:27:28] You probably have a reverse effect there where your tolerance to cold, I would imagine is lower as your heat adaptation goes up. Or is that something that doesn’t conflict? So that’s something I’ve been interested in a while. And I tried to find research on it forever because my thought was exactly as similar to you is that.

[00:27:46] You were thinking along the lines of the said principle, like adaptation to cold and heat are probably on opposite ends of the spectrum, right? So my thought was, okay, do they conflict with each other? So if you have someone who, let’s say is getting ready for a huge race in Phoenix, should you not have them do like a lot of cold water stuff because you’re getting them to adapt more to a cold stimulus when they’re going to compete in a hot environment?

[00:28:09] I can’t find anything that says that’s true. The mechanisms overlap a little bit, but not exactly. So what I do with athletes is I call it the barbell method. So just like you would for any other quality you want to develop, just take what you have access to first and let’s do that. So if you’re in Minnesota and you only have a cold water tub, like let’s just do some cold adaptation first, let’s not worry about heat.

[00:28:34] If you’re in a hot environment or you have access to a sauna. Great. Do the opposite end. Do some heat adaptation first. Once you get pretty good at that, then kind of put that on hold. Maybe not do it at the same thing. Maybe do it once or twice a week, and let’s go to the other end of the spectrum, and let’s say you’re working on hot.

[00:28:51] Now let’s go to the other end of the barbell and work on cold. Once you get pretty good at that, then I would actually have them do contrast therapy back and forth. Because, I don’t think contrast therapy is bad, but to me it’s It’s much more advanced because you have a cold stressor, you have a hot stressor, and you have to switch back and forth extremely fast.

[00:29:12] Um, some of the literature shows that there is potentially some benefits to that, but what I’ve realized with athletes is it’s virtually impossible to troubleshoot because I’ve seen multiple athletes now come in where their HRV scores are all just completely screwed. And it’s like, I’m like, bro, what are you doing?

[00:29:28] Like, Oh, I just got this cold tub the other day. They put the sauna in and I’m doing this crazy contrast therapy back and forth, you know? And so they went from like nothing to like, you know, balls out, whatever protocol they got off the internet and their HRV scores are just, just dropping like a rock.

[00:29:44] But I don’t know at that point is, was the sauna too hot? Were you dehydrated? Was the cold too cold? Did you switch back and forth too much? Did you do too many rounds? There’s so many variables to troubleshoot. It’s. You can scale them all down and just kind of go with it. Um, so usually I just have them pick, okay, what do you have access to?

[00:30:01] What’s more specific for your needs? Let’s work on that. Cool. We can monitor that and make sure you’re not overdoing it. Cause I have seen CrossFit athletes do a little too much on the Wim Hof and the cold water immersion and just completely tanked their HRV. And it took me three days to figure out what the hell they were doing because none of their parameters changed.

[00:30:21] I said, you have to be doing something different. This has happened three days in a row and they’re like, Oh yeah, I added cold water and like 20 minutes of Wim Hof in the morning. So yeah, um, so yeah, just pick one, go that, make sure that’s good and then expand the other one and then you can kind of, you know, go back and forth.

[00:30:36] And another trick I’ll have people do is if you’re doing like contrast therapy, do it like on a usual program and on a Sunday where like Sunday is completely off. Like just, just walk, do some mobility, like just chill out. And that way I know if Monday is completely screwed and you’re not back on track.

[00:30:53] I know kind of what did it, if you kind of toss it into your other training, unless you’re pretty well documented of how you respond to that, it’s harder to figure out. Um, and again, the goal is to try to increase your recovery, which to me is just get back to baseline faster. Um, that way on Sunday you’ll be able to look on Monday and then you’ll obviously have your performance data on Monday to see how that’s going.

[00:31:14] Yeah, interesting. Yeah, it’s cool stuff. I, I wanted to talk to you about, uh, ketogenic diets as well, because you’re the metabolic. Oh, and I wanted to say one last thing on the call. Yeah, go, go for it. We’re going to email and go, he said he’s going to talk about hypertrophy. You never know. That’s right. Yeah.

[00:31:28] Yeah. So there’s about four really good studies looking at muscle hypertrophy in cold water immersion. So the studies that did that, it was around 10 to 20 minutes at at least 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Uh, by the part that you worked on, which mostly was lower body is completely submerged and it was done immediately after training and in those studies, it is correct that they did see not as much hypertrophy compared to the group that didn’t do that at all.

[00:31:58] So if you go anywhere online, people are like, Oh my God, don’t do cold water. It’s destroying all your gains. Um, like we talked about for strength and power, it’s much more of a mixed bag. Um, so for the physical X course, I spent God forever. I went through all the studies went through everything I could find because in my brain, I’m like, okay, what in plain English does this actually mean?

[00:32:18] Right? Cause you well know that you could see an effect size and you could see something that’s statistically significant in a study, but it could be so small that it doesn’t matter. And again, it depends on the context. If you’re an elite level athlete, those small changes could actually be highly significant to you in terms of your performance, even though it was very small in the study or maybe even non significant.

[00:32:38] So I was trying to figure out, I’m like, okay, let’s say you’re just a crazy hyper responder to hypertrophy and arbitrarily you can gain one pound of lean body mass per month, right? Which is way on the high end, but just make simple math, right? So one year you would gain 12 pounds. Okay, so if I’m, I’m a bro and I’m doing all my training and my goal is only hypertrophy and I’m doing cold water immersion after every single session and I’m doing it exactly the way it was in the studies, which most people are not.

[00:33:07] Let’s say they are, what does that cost me? Is that costing me three quarters of that pound? Is that costing me half a pound? Like, half an ounce? Unfortunately, I don’t have the answer, which annoys the crap out of me. Because some of the studies used muscle fiber changes. So they could see on muscle fibers, there was a difference in hypertrophy.

[00:33:28] Some of them did use DEXA, but it was probably below the limits of the DEXA. Again, if you pool all the people together, can you show there’s a difference? Yes. Can you figure out exactly what that difference was with any reliable confidence? Unfortunately, no. Um, so it probably is an effect. I don’t know what the actual number is.

[00:33:47] My guess is it’s probably on the lower scale. And the other part is we don’t know is what happens after the study is done, right? Does your body have an increased accelerated gain to try to make up for that? Um, we do see some of that in people who train really hard, who are on reduced calories. There’s kind of, quote, these makeup gains a little bit that accelerate after that period of time.

[00:34:09] Um, so we don’t know any of that. We do know that the mechanism is it does appear to directly affect what’s called muscle protein synthesis. And it appears to downturn that process directly. So that’s how well your body takes incoming protein. It takes amino acids and shoves them into muscle tissue to make it bigger and stronger.

[00:34:28] So we do know that cold water immersion done immediately after does turn down that process. We don’t, we’re not quite as good about the changes in the chronic setting. There’s only been a couple studies that have been done on that. Last part is in healthy individuals, I can’t find any data for cold water immersion that it actually changes inflammation or is actually anti inflammatory, which kind of goes against everything that’s said online.

[00:34:55] Um, so one of the main studies from Van Loon’s lab looked at TNF alpha, looked at a whole bunch of different markers. 20 minutes, I think, of cold water, like 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Um, they did see muscle protein synthesis was reduced. They did see less, um, quote unquote gains in that study. Um, however, if you’re looking at a pathological population, yeah, you may see some modification of inflammation.

[00:35:20] I don’t know in that case. Um, but the prevailing wisdom online was, Oh, it’s anti inflammatory and because it’s anti inflammatory, like some NSAIDs and some antioxidants, that’s what’s blunting the muscle hypertrophy effect, which does not appear to be true. It appears to be some Regulatory mechanism directly on the muscle protein synthesis rate.

[00:35:40] Hmm. Interesting. Yeah. Cause then even if, if we do look at it through the lens of anti inflammatory, it’s like, that could either be good or bad. Right? Exactly. Yeah. It’s like, what, what part of that process are, is it acute after a workout where you actually want that? Or is it chronic inflammation that is giving people all sorts of issues or?

[00:36:01] Inflammation disorders has become kind of a catch all word that people use to describe any discomfort, I find. Yeah, and a lot of it is biphasic, too. Like you said, like IL 6, you probably want that to spike after training, but then you want it to come back and normalize. You don’t want to be running around with Crazy high levels of IL 6 all the time either.

[00:36:20] Right? So it’s a lot of these responses are Acutely, we probably want some inflammation like reactive oxygen species. We probably want some of those. Those are cellular Markers that we did some damage and we have an effect that we want a positive adaptation But you don’t want to be going like batshit crazy like 24 7 either.

[00:36:37] Cortisol is the same way Like, if you can’t elevate cortisol, your training’s gonna suck. Yeah. But, you don’t want to be walking around all day trying to go to bed with, like, cortisol levels that are sky high either. Yeah. You know, so it’s the, the interplay of, you want that to be back to what is, quote unquote, more normal.

[00:36:56] Um, but that gets more complicated. People want to know like, Oh, cortisol is a good or bad. Yeah. Right. Oh, I heard it’s bad. Yeah. Interesting stuff. Yeah. So I was curious if you had any information or info on the more recent study that came out about a low carbohydrate. Actually, I mean, it’s basically strict ketogenic diets.

[00:37:18] Cause I think the, the keto arm on that study was 50 grams, which with a endurance athletes is going to be a ketogenic diet. Oh yeah. No matter how you define it for the most part. And it was, it was by a Nokes Plews. I believe there was another, another, another author included in it. But it was interesting cause it’s, they, they ran.

[00:37:41] They ran a group of, I believe it was 10, 10 participants. They were like, uh, they weren’t like elite athletes, but they were top tier. If like eight, I guess you maybe call them age groupers or something like that. And they’re training in like the neighborhood of probably like 30, 40 miles a week, if I recall correctly.

[00:37:58] And they, they put them through a battery of more like. Higher intensity like speed work type stuff to try to tease out whether the ketogenic diet was going to be a performance deficit in in the context that they had it. And, uh, I mean, they did the same group with a washout period. Um, it looked like it was a reasonably done study for the purposes that they were trying to explore.

[00:38:18] And they found like no issues in terms of performance with that group. They also found that three out of the ten participants when they went back and did the Moderate to high carbohydrate diet were actually pre diabetic, which was resolved with the ketogenic diet. Which was suggesting, because none of these individuals were gaining weight on that, and if anything, I think all participants lost weight throughout the study.

[00:38:44] So it was suggestive that it was something unique to carbohydrate endurance in relatively fit and healthy people, that there’s a percentage of the population that, that’s just not a good combination for if we’re looking at blood glucose control anyway. So I was curious, I mean, I’ve got questions. I don’t, I’m not criticizing the study on this.

[00:39:04] I’ve got questions about the performance side of it because I don’t think, I don’t think they probably had the ability to do a test that would actually answer the question that I have, which is like, how does that play out when it’s actually being put in a training cycle of, I’m not just going to send you out for one random three minute VO2 max session or one mile time trial.

[00:39:25] I think they were doing eight hundreds if I remember correctly. I’m going to have you doing like a short interval session, a threshold session, a long run. I’m going to have you cycling that for like three weeks before I give you a deload week. My question is always like, I understand that someone can go and execute a short interval session on a ketogenic diet, but when can they replicate that relative to someone with more carbohydrate included in the, in the mixture, whether that be just.

[00:39:49] Pivoting from strict keto to low and being kind of more strategic with the carbohydrate uses or just full on moderate high carbohydrate Because my own personal experience is that yeah If I could I could sit strict keto 50 grams a day for weeks and then go out and just nail a 400 meter Repeat workout, but if you asked me to do that workout again, I would need more time.

[00:40:08] Yep to do it again. Whereas if I introduce even introduce carbohydrate just around that workout and then go back to a lower carb diet after that, I’m going to be able to replicate sooner. So do you find if you had to do 400 meter repeats that you’re performance in session or in repeat two, three, four, five, six, kind of drops off faster.

[00:40:29] No, I don’t. I actually find that any, I mean, I’m sure I could get to a point where it would probably be a problem where, okay, now, now if I don’t introduce some carbohydrate, My performance will suffer. And if I do, I’ll be able to go to a few more reps. Sure. The question I always have with that is, are those extra reps necessary or are they detrimental?

[00:40:49] Because are they going to put you to, I like to describe short intervals as leave a couple in the tank. Yeah. Leave a couple in the tank. I’m repeating that session sooner. And that repeat session is going to be way more than the couple extra I do if I go too far. Yeah. So in some regard, I think you can look at carbohydrate is almost too potent to a degree where if it.

[00:41:05] It allows me to do a hero workout when I should have stopped, then it’s actually could potentially take more off down the road to, um, in, in, in certain circumstances. But that’s always kind of my, my, my second question when I see like, you know, a good workout on a strict ketogenic diet relative to, you know, any sort of carbohydrate.

[00:41:27] with that when we’re talking about moderate to high intensities. Um, so I think like I actually found the pre diabetic part of that study way more interesting because most people are looking at endurance athlete primarily through health. They probably have performance goals, but unless you’re an elite athlete, you probably don’t want to drive diabetes in order to achieve your PR at the Boston marathon.

[00:41:49] So if it is a 30%, um, Percent of the population, which I get 10 people, you know, needs to be replicated. We need more participants. We need to really fine tune what that number, assuming there is a signal there. We need to figure out more precisely what that number actually would be. And obviously ways to have people to figure out if they’re in that group or not.

[00:42:11] But yeah, I was just curious. Had you looked at that study at all? I just looked at it briefly. I haven’t read it in detail yet. Um, my takeaways were similar to yours that. I would have expected more of a speed and power kind of drop off, but if I remember right, they were not, they were trained, but they were not like super high level people either.

[00:42:32] And this is the same thing with training for any speed and power. It’s like, what is your baseline? You know, if your baseline is you haven’t done a lot of speed and power training, so you’re at a much lower level, then nothing’s probably going to make that much of a difference, right? If you’re at a very high level.

[00:42:49] Now you’re one more sensitive to it and a small drop off is going to be more, more present, right? So some of the work I did with cyclists, we would put them on a ketogenic diet and even like speed and power, like ability to pass people, that kind of stuff. Like if they were an average, I’d say, okay, rider, it didn’t really change a whole lot.

[00:43:07] Um, but as you scaled up to a handful of people who were higher level, I wouldn’t say not necessarily elite. They became much, much more sensitive to it. Like, a couple of them got super pissed. They’re like, what did you do? This is stupid. I wanted to pass this dude and I couldn’t pass him. I was trying super hard.

[00:43:23] And they, most of them report, they just, they feel like they’re missing that last gear. They feel like they’re trying really hard for these sustained bouts. Even within an endurance event, they just can’t seem to replicate. Um, so I think it, the higher level athlete you scale up to, that’s going to become more important.

[00:43:41] Um, and years ago, I never. I guess I never believed that. I just thought, you know, if you’re doing ultra marathons and ultra these long events, then at some point, if the event’s long enough, like speed and power just won’t matter. And I remember, uh, volunteering for the Ram race and we were somewhere in the middle of fricking Nebraska or something like that.

[00:44:00] And as a four person team, and we had a guy who just bored. And so there’s no drafting. And so he would ride up behind the guy and then he would just keep backing off. And so you’d see the guy in front, like get kind of nervous cause he didn’t want to get passed and then he would back off. And so we told him like, okay, like the fourth time, just, you know, just, just go by him.

[00:44:20] He’s like, all right. And so we’re in the car right outside him as he’s passing them. And you see the other rider just trying to go as hard as he could, cause you could tell like he just did not want to get passed. And he just, our guy just blew by him. And the look on that guy’s face was just morally just defeated.

[00:44:38] He just looked like he got crushed. And then I realized I’m like, oh my God, like day three into a seven day race, like speed and power still matters. Um, so, but back to the study, I think that if, if you’re at a moderate to intermediate level, I think ketogenic can be beneficial. Um, as you’ve noticed too, probably a lot of people have issues with carbohydrates, whether it’s a GI intolerance, whether it’s all these other things you have to kind of watch out for.

[00:45:07] Um, related to health, I’ve seen, uh, basically no crossover period or no crossover effect in some high level endurance athletes. So for listeners, as you would do a max test on a metabolic heart, you would see them start out using mostly fat, fat, and then over time they switched to using mostly carbohydrates.

[00:45:26] Um, I’ve seen from a couple of guys where they started out just burning through carbohydrates and they never got down to 50 percent fat use at all, ever. Now their performance in races was pretty damn good. But then when you interview and you ask them, they’re like, okay, what, tell me about the races that just didn’t go well.

[00:45:45] It was always, oh, I had a problem with the fueling station or I had GI upset. Like they couldn’t keep that level of carbohydrate in to match their output. So they had like a really big engine, but it was only used to carbohydrates. And so I’ve wondered about that level athlete. They may still perform well if they time carbohydrates and they get lucky and everything goes well.

[00:46:07] But in the back of my head, I’ve always wondered, I’m like, I don’t think they’re doing their health any benefits. Um, and there is some studies looking at humans and rodents that how well you can use fat as a fuel at lower to moderate intensity exercise does show up in longevity. It’s, it’s not, it’s hard to do a direct one to one relationship with that.

[00:46:26] Um, so for most athletes, I would encourage them, you know, to try to use more fat and then you still want to be able to switch to carbohydrates. And you want to move that fat oxidation or fat max as high as you can, but the higher level you go as an athlete, I still don’t want to compromise that carbohydrate and because I think that’s still going to be come important at some point, um, which again, isn’t the simple answer, right?

[00:46:51] Because you’ve got, as you well know, right, you’ve got the whole field saying ketogenic diet is the best thing ever for performance, for health, for everything. And then you’ve got the high carbohydrate people are saying, no, no, but it’s bad for performance. And everything else. And to me, the reality is it’s more metabolic flexibility.

[00:47:08] At some point, should you be able to do a ketogenic diet? I think you should be able to down regulate and get to that phase. Should you be able to start out using mostly fat? And should you be able to transition to use mostly carbohydrates? I think if you can do that, you get both a performance increase and, I think, overall, you’ll be more healthy.

[00:47:26] Right? Because we know looking at a progression of, say, diabetes. So most people when they think type 2 diabetics, they think, Oh, it’s just a carbohydrate metabolism issue. And that’s what I used to think too. And yeah, there’s definitely some issues with carbohydrate metabolism, but the simplistic version of it is, over time the body’s solution then is just to keep putting out more and more insulin.

[00:47:46] Right? It doesn’t want to have a whole lot of blood glucose hanging around the bloodstream. So the solution is, let’s put out more insulin. If we put out more insulin, that’ll drive the blood glucose out and just, just get it the hell out of the glucose in the blood. Put it in the liver as fat if we have to, put it in the muscle as fat, store it somewhere if we can, just get it the hell out of the bloodstream.

[00:48:06] So we know that’s going to be bad. But then over time as insulin levels, your baseline gets higher and higher, it impairs your body to downregulate and use fat as a fuel. So your metabolic flexibility gets crushed from both ends of the spectrum where you can’t really upregulate and use carbohydrates all that well to where you should.

[00:48:25] And your insulin levels are so high, it’s harder to downshift to use fat all the time as a fuel, too. So you kind of get crushed from both ends of the spectrum on it. Yeah, it gets interesting. It’s one of those things where it’s almost to the point where getting some tests done are probably going to be helpful in recognizing where you’re at.

[00:48:45] So you’re at least not just, you know, grasping for things in the dark, so to speak. Hey folks, just a quick reminder that this podcast sponsors include S fuels. They have a 15 percent offer for you element electrolytes. They have a free sample pack offer for you. Janji apparel has a 10 percent offer for you and Delta G ketones has a 20 percent off and free consultation offer for you.

[00:49:11] Links and details can be found in the show notes and the episode landing page. You can also check out a full description of how I use all of these products in my own training and racing at the end of this podcast episode. You know, I had, uh, Dr. Dan Plews on to talk about that study. Yeah, I love his stuff.

[00:49:26] Yeah, I know. He’s got great stuff. And, and, shout out to Dan too. He just was, he broke the age group, uh, Ironman record. Oh, wow. Recently. Went under eight hours. Oh, shit. 758 or something like that. Yeah. That’s crazy. So, yeah. So he’s, he’s proven it in himself a little bit. Cause I know Dan is a more of a low carb guy.

[00:49:43] himself, but not strict ketogenic to what I understand. Certainly not during the race either. He’s, he’s definitely a advocate of kind of right fuel, right time approach of there’s going to be points where, like what you’re describing on that, that, that Ram event where he’s going to be. he’s kind of like, where you’d want that or how you can maybe just the different levers you can pull to improve that oxidation.

[00:50:12] Because yeah, people sometimes just think, oh, it’s a carbon fat thing. But in reality, like If you look at it across the board, it’s like, if I change nothing about my diet and introduce endurance training, I’m going to improve my fat oxidation from that, or maybe I just repartition the carbohydrate from like near the workout to later in the day, I might even get some improved fat oxidation from that.

[00:50:34] Uh, I mean, we see this from moderate carbohydrate athletes from time to time where they’ll do a fasted long run at an easy intensity where it’s likely not going to be problematic for them. And, you know, over time they can improve their fat oxidation rates to some degree anyway. Um, obviously you need to test to kind of pinpoint where those are, but the big lever is always going to be just restriction at the end of the day.

[00:50:51] So then it becomes that balance of performance versus fat oxidation improvement. And I always tell people, look at that on a spectrum because you likely don’t have to be as fat, fat adapted if we’re going to use that word as you could get, which would essentially just be the elimination of carbohydrate, right?

[00:51:09] Uh, so if you don’t need to be that fat adapted, that means you’ve got some flexibility with the carbohydrate side of the equation. So let’s find where that spot is and then kind of end up in your world a little bit more where you sort of are able to pull both those, both those levers a little bit more.

[00:51:24] Yeah. It’s like any other to me, training quality, right? Like you could, so the data, right, as you know, looking at VO two max VO two max is one of the indicators of high level performance, but it’s not the single indicator. There’s plenty of top level athletes who have a very high VO2 max, but it’s not the highest and they, they do fine.

[00:51:45] Right. Otherwise we’d just go, what’s your VO2 max in the lab? And be like, bet tons of money and be like, Oh, there’s a winner. Yeah. Right. And you’ve got other people who have a much higher, you know, lactate threshold or whatever, you know, ventilatory threshold, whatever words you want to use for that, or they can basically go at a elevated pace that is a higher percentage of their VO2 max.

[00:52:06] Um, so there’s not just, One thing, and what’s fascinating is When you try to increase your VO2 max, you can, but it seems like the percentage you can use goes down then. And so then you try to increase the percentage a little bit and your absolute max goes down a little bit. So I think of this as a, a guy I know is one of the top coaches for track athletes in Europe.

[00:52:29] And they had a, I think it was a 200 meter, I think it was a female, uh, race. And her top end was good, but her acceleration was always not the best. So I think they took, I think a four year cycle to get her acceleration up to where it needed to be. She’s already like elite level human and her top end actually went down.

[00:52:51] So her time was about the same. And I think they flipped it the following year and they saw basically the exact similar result again. Where like, you could increase one of them, but you dropped the other ones so much that your time didn’t really get better. So there seems to be these kind of ceiling at the highest, highest end that you’re playing with, where yeah, you may increase this one variable a little bit, but the next one is going to go down to try to compensate a little bit.

[00:53:18] But I think the variables, like you mentioned, that most people can play with that they don’t think of is, okay, how high can I get my fat oxidation? However, I don’t want to long term inhibit my body’s ability to use carbohydrates. I don’t want to completely kill all my speed and power, right? Because you could.

[00:53:36] You know, get completely, you know, fat out of the fat adapted and probably get those last few percentages higher. But I’d be willing to bet your race times are not going to get better. Where, like you said, if you’re a little bit below whatever your capacity is, but now your carbohydrate metabolism is also higher.

[00:53:52] So your overall system is at a higher level, then you’ll see an increase in performance. But again people want to hear oh, if I just get fat adapted I’m gonna win races or never use ketones or never worry about fat. Just use carbohydrates only And again, like most of what I’ve seen from you know, very high level humans is that they’re really good at using fat They can use some ketones and they’re still really good at using carbohydrates Or if you’ll get mixed up as they may look at certain parts even this happens with you I’m sure of your training where okay that my goal of my training here is to try to use fat more So I’m gonna like you said restrict carbohydrates and move timing around and be more fast in training But they’ll only look at that period of training and be like, oh, bro Like this is what you do all the time.

[00:54:33] Like I heard Zach. He doesn’t use carbohydrates. They’re horrible for him Look at his training over these, you know six week period. Yeah, but that’s part of a year long four year, you know plan It’s just one portion of it Yeah, it is funny. I that one of my favorite things to do if I have a good race is to see like people argue about Whether I am mainlining carbohydrate or not having it at all.

[00:54:58] because yeah, it’s like you said, it’s like you have to look at the whole picture, not just one segment. ’cause yeah, you can cherry pick a section of my year where, oh yeah, you could say he’s ketogenic. Yeah. By gram even. And you can pick a portion of my year where like the amount of carbohydrates I’m taking in.

[00:55:13] Would look like moderate carbohydrate someone who’s not doing the output I’m doing but no you introduce a 20 hour training week into the equation All of a sudden you have a situation where now we’re looking at it as like you just put fast forward on your metabolism You know for me, I might be two sometimes three axing my resting metabolic rate in a day’s time So it’s like what gram actually produces what ketones in that?

[00:55:34] that particular picture. So it gets really messy when you’re, when you’re making those sort of lifestyle decisions, I guess. Yeah. Do you find the training volume that as you increase the intensity at volume, that you feel like you’re benefiting more from carbohydrates at that point. Does that make sense?

[00:55:52] Yeah. I would say it’s way more linear when I just do, when I increase low intensity volume, it’s a fairly linear amount. So if you looked at it like, let’s just say for example, if I’m just going about my day without doing any training or any, any real training, maybe three days at the gym or something like that, 50 grams, maybe even a little lower, it’s probably going to need to get into like a routine ketogenic state.

[00:56:13] Now all of a sudden I, introduce say two to three hours worth of exercise into each one of those days. Low intensity. It’s going to be more linear in terms of what carbohydrate I can add into that. Sure. And to some degree there’s, there’s a little bit of flexibility there within, cause you do have these like boluses of higher energy output.

[00:56:35] It’s not just like a straight energy curve or a straight energy line. It is kind of like, A big bump of energy and then kind of back to normal big bump of energy as you go do a two or three sessions or something like that. So there is probably a little bit like I could get away. It’s a little less linear if I’m partitioning the carbohydrate during those higher energy boluses versus having them kind of more evenly spread out or even away from those.

[00:56:56] Um, I find like in that, in that scenario, it’s a little more predictable. Now, I take that same situation, maybe I bring volume down even a little bit, um, because my peak volume is like long run development. So there’s just, I’m basically like crowding out any room for intensity at that point. But if you go back a little bit earlier in the plan, my, my volume is still quite high and I am introducing that intensity variable or maybe two, three days during the week.

[00:57:20] I have a moderate or higher intensity workout session in there. That’s where I find I have to be a little more liberal with carbohydrates in total and, and just like lean into that a little bit. It does tend to be something where at that point I’m way more precise about where I’m putting them. So say Tuesday, I’m doing short intervals.

[00:57:38] I might the meal before whatever workout that is during that workout. After that workout, I might have like a pretty congested amount of carbohydrate that I will eat over that next 24, 36 hours, just more hyperlocated around that session. Um, and that’s, that tends to work a little. So, so even if that, whatever gram Average, that would work out to over the course of the week.

[00:58:00] It’s not a rinse and repeat one day to the next. It’s like one day might look aggressive on carbohydrate. One another day might look quite low because you know, a big workout, high intensity or moderate intensity workout is usually followed by something pretty light the following day in that time, that training phase.

[00:58:16] So I tend to, sometimes what they put as I borrow carbohydrates from different days to kind of congest them around the workload that is going to be more necessary for those. And I found that works pretty good. Good. In terms of replicating kind of the, the, the workout like targets that I’m trying to aim for Yeah.

[00:58:33] Kind of the, the framework I’ve used, I’d be curious on your feedback on this is what I call like a eustress model. Mm-Hmm. . So you have like a eustress or a distress. So eustress. A eustress is stress that your body can more easily recover from. Mm-Hmm. . So distress would be stress. It’s much more harder to recover from.

[00:58:50] So for most athletes, like competition day is a distress. It doesn’t really matter what’s going on. Performance is the only thing that matters. I could take all of next week off if I have like a, just a big race and that type of thing, but if I do like Monday is like the world’s biggest volume day, man, I might be crushed for five days.

[00:59:07] So now I can’t train for five days. So now I’m missing out on those other days. We’re training. I look as a eustress model. Can you get some good work in? Can you come back the next day? The next day, the next day. So with that, I have something I just called macro matching. That the higher intensity work, more speed, you know, volume, like the VO2 repeats.

[00:59:26] I would have people, in general, starting with more carbohydrates during those times. And then the lower intensity stuff, which is more fat based, then I would just pull carbohydrates back. So you’re trying to use the fuel that you’re going to burn in the session. You’re trying to load more of that fuel so that the intensity of that works.

[00:59:44] And then the progression over time is to actually get to a point where it’s actually almost a distress training. Or now you may go into a session like you’re talking about and purposely do higher intensity work, but not provide any carbohydrates. Right. I’m not really looking at the performance per se of that session.

[01:00:02] I want some of these adaptations by not having carbohydrates present. And you can go even further and actually purposely deplete liver glycogen and try to deplete muscle glycogen and then do some heinous, you know, repeat type stuff where you will see an upregulation of all the enzymes that match that.

[01:00:20] But your performance is definitely lower. Your stress is astronomically crazy. The research on that is like still split probably 50 50, if there’s any big advancement in that or not. But that’s kind of the framework that I use for people to kind of pick where they’re starting and where to go. And what I find is most people kind of find what works best along that spectrum, but that’s only, like you said, over time and doing their testing and seeing what works for them.

[01:00:46] Um, which again, people want to know, well, I just want to do my long runs fasted and then have carbs for high intensity. Great. That’s, you know, that’s a good place to start. It doesn’t mean you’re going to stay with that simple model like your whole career either. Why it gets messy. Yeah, for sure. Yeah. You, you want to kind of pay attention and it, I mean it’s almost similar to like diet strategy in general where someone like Picks a dietary practice and it’s working great because they have a lot of weight to lose They’re like seeing a lot of success and all sudden like they plateau At that like lat when they have that last bit to try to take care of and they just think I need to do this harder Yeah.

[01:01:28] And it’s like Just try harder, bro. Yeah. Right. Right. Yeah. Where in reality, it’s like you may just be at a point where the strategy you were implementing was great from where you were at to where you got, but now it’s time to adjust it to something else to get continued success. But, but they can’t get past the fact that they had success with it in the early stages.

[01:01:46] Yup. And they keep kind of just driving the same thing and they don’t get to the end goal ever, ever with that approach. Yeah. That’s why coaching is so helpful. Obviously, I know you coach a lot of people too. Is that Neurologically, your brain is associated all those past successes with approach number one.

[01:02:02] And so for you to do, even when it stops working, you unconsciously are thinking but this always worked in the past. But what people forget is what you said is they’re at a little bit different point now. So then maybe they’ve evolved past that and they have to kind of do the next thing to get to the next level.

[01:02:19] Which you see that in a lot of athletes get very stuck in what they were doing. They’ll reach a certain level of success. But then it’s kind of a gamble at the next one because, okay, to get to that next level, you’re probably going to have to do something that’s a little bit different than what you’ve ever done before.

[01:02:34] And we don’t have any history of that. There’s no way to 100 percent predict how you’re going to respond. So let’s try a little bit. Let’s see how you respond. Let’s kind of slowly work you up in that direction. Um, so even when I write plans for athletes, I always think of, okay, if this goes well, we’ll, we’ll be good.

[01:02:50] If it doesn’t go as well, then I set it up in a way that I know for sure what to do next. You know, so at least if they did three weeks and it wasn’t progressing I can be like, okay cool I thought that was going to work. It didn’t but I know we need to go in this direction now So try to think like those two steps ahead because there’s nothing worse than program for three to six weeks.

[01:03:10] They don’t get the result and they go, Hey coach, what do I do now? And you’re like, shit, I don’t know. Or not have the next step outlined to the degree where now you make another mistake in the next, right. The next thing you’re just going backwards then it’s yeah. Yeah. Yeah. That’s not a good setup either.

[01:03:25] Um, I want, as long as we’re on the topic of kind of metabolic flexibility and kind of fat oxidation. So I did want to kind of pivot to the other direction and, uh, because last time we chat, this hadn’t really caught momentum yet, where I think last time we spoke, they were, we were still working on the model of like roughly 90 grams of carbohydrate per hour.

[01:03:43] And some of these like top tier, like high carbohydrate based approaches to like tour de France. Now they’re pushing that number up to like 120 and sometimes beyond grams per hour, which I think is just. It’s interesting for a number of reasons. One of them that I wanted to hear your take on is from what I understand, they’re not experiencing any sort of performance improvement acutely by doing that by say, let’s say someone normalizes 80 to 90 grams per hour for their.

[01:04:14] Carbohydrate based approach, and now they go up to 120. They find a way to make that work and they may not have a faster session by that extra carbohydrate, but there may be some application where they recover quicker because of that. So then the argument would be. If you can create a model where your workouts are able to tolerate 120 grams of carbohydrate per hour, maybe you can replicate those more frequently and therefore over the course of a training plan, potentially increase your training load capacity and therefore ultimately race faster.

[01:04:46] That’s how I’m understanding the logic. I would like to hear if, if you feel one way or the other. Yeah. My guess is based on what I’ve seen, I would agree with you right now. Now I will say that. I’d be curious if there are complete outliers who may be able to actually quote unquote use that amount of carbohydrates, and would their performance be that much better?

[01:05:11] Probably? Um, and a lot of that I think we got at like, uh, JeckandDrop has, you know, published some stuff showing that the gut is actually trainable in terms of how many carbohydrates you can take in. So I think that was one thing in the past that people felt like was very fixed. You know, they would test and be like, Oh man, I only got to 50 grams per hour and I can’t do any more and play around maybe different types and timing.

[01:05:34] And I think the background assumption was, okay, for you, that’s fixed. Well, now it appears to be trainable. But then the question like you asked is, well, how? How high can we go? And what is the benefit? And you kind of see this curve where it just kind of plateaus at the top. But, they appear to get more high quality volume in over the course of a training spectrum.

[01:05:57] And all things being equal, if you can get higher quality of volume in and you can recover, you’re probably going to get a faster adaptation with, you know, whatever your baseline was. You’re probably going to get a better training response. Um, from the physiology, everybody probably at some point has a different limiter for performance.

[01:06:17] And I don’t think we a hundred percent understand what that is, whether it’s heat dissipation, whether it’s blood flow, whether it’s muscle uptake, whether it’s a bioenergetics thing, whether it’s, you know, obviously notes with the central governor hypothesis, which. It’s super cool. And I, I think that’s probably true, but it’s virtually impossible to test also, you know what I mean?

[01:06:38] Yeah. So on one hand, I’m like, wow, that’s so brilliant. I love it. And that seems to just make sense with everything that I’ve read, but frustrating because How the frick do we test that? We can’t really test it. We can do these kind of indirect tests where you move the finish line and you know, all this other kind of stuff and um, Yeah, so all that to say the last thing I think of too as Like a tour de France rider or something that just the amount of absolute punishment They have to go through like day in and day out because it’s a multi day Event or even you know longer races that type of thing.

[01:07:17] I just in my brain. I just keep coming back to okay What is a medical model that would try to replicate that? I just keep thinking about like the burn patients like patients who are just so catabolic. I talked to dr David Church about this It’s like, okay, in those patients, what is most beneficial? And it’s testosterone because it’s so anti catabolic, you know, potentially maybe even insulin, you know, just because like you can’t really give them enough amino acids.

[01:07:47] It’s almost impossible to give them enough fuel. Um, and then you look at, you know, why people use other performance enhancing drugs. Like you think of like cycling, you’re like, I want to just be EPO and everything that enhances performance. But you find. People have been popped for testosterone many, many times, which again, I think gets back to the recovery aspect.

[01:08:06] So again, maybe if you’re someone who can take in that many more calories, you can get that many carbohydrates per hour absorbed past the gut. Maybe that does hedge your bets a little bit more so you’re not so So for lack of a better word, catabolic, you can get back to baseline, uh, faster and therefore you can kind of get back in and recover the next day.