Join me, Dr Mike T Nelson, on the Flex Diet Podcast as I welcome Paul Oneid to discuss all things strength and body composition. We explore the intricacies of developing strength, emphasizing its role as a skill-specific measurement of output.

Listen in as we discuss the importance of task-specific practice and how different athletes may require varied training approaches based on their unique physiological traits. Paul shares insights on central nervous system fatigue, the necessity of customized training protocols to achieve peak strength, and much more.

-

(0:00:00) – Improving Strength and Body Composition

- (0:11:52) – Adjusting Taper Lengths for Different Lifts

- (0:18:36) – Optimizing Performance Through Training Strategies

- (0:27:44) – Fine-Tuning Meet Performance Strategies

- (0:34:54) – Muscle Mass and Strength

- (0:48:02) – Maximizing Strength Training Complexity for Progress

- (0:59:19) – Optimizing Training for Strength Gains

- (1:09:23) – Balancing Priorities and Training Goals

- Tecton Life Ketone drink! Use code DRMIKE to save 20%.

Flex Diet Podcast Episodes You May Enjoy:

-

Episode 215: Breathing, Heart Rate, and HRV: An Interview with Dr. Scotty Butcher, The Strength Jedi

- Episode 149: Strength, Hypertrophy and Training Research Update from the REC Conference by Discover Strength 2022

Connect with Paul:

Rock on!

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

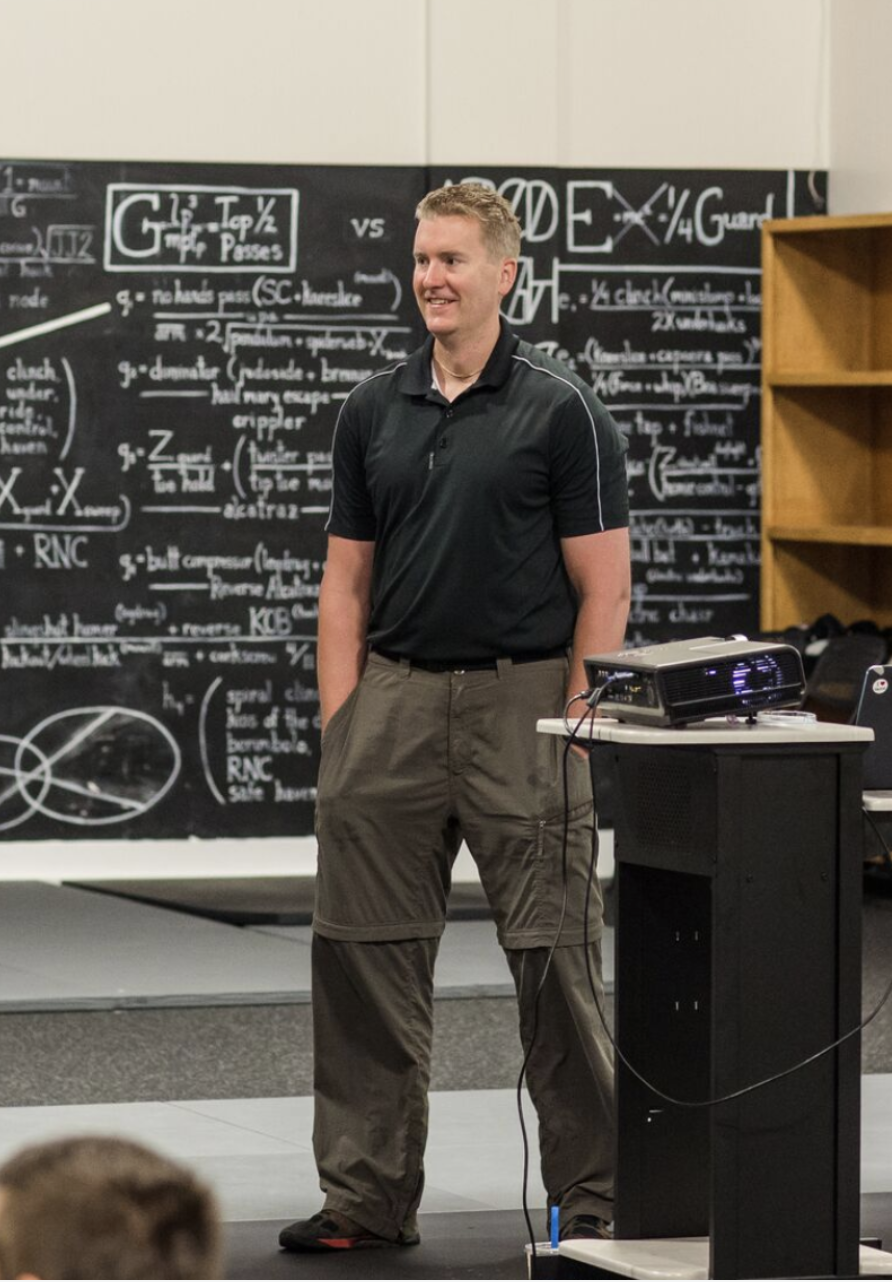

[00:00:00] Dr Mike T Nelson: Welcome back to the Flex Diet podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T. Nelson. On this podcast, we talk about all things to improve your body composition, increase strength and muscle, and do all of it in a flexible framework without destroying your health in the process. Today in the podcast, we have Paul Oneid.

And we talk all about strength. This is strength in the gym. How do you increase it? The role of muscle mass. Do you really need more mass to just move mass and all their aspects of strength, even talking about Louie and West side, different concurrent conjugate approaches Paul shares a lot of great stories of.

The different approaches he uses with his athletes. And we also discussed the role of physiology and. Psychology about how both of them are important and different strategies for taper heart rate, variability, regulating volume, and a whole bunch more great stuff. So this podcast is brought to you by me on my newsletter.

You can hear more for me. Just go to MikeTNelson. com and there’ll be a little button on the top. It says newsletter, and we’ll put a link down in the show notes here below, and you can hear daily updates from me for free. It’s basically very similar to this podcast and all things to improve your body composition, more muscle and more strength also brought to you by Tekton.

They are the manufacturers of a. Exogenous ketone beverage. So you might be wondering why the heck would I bother using ketones? What’s super cool about exogenous ketones is that you can consume them as a supplement, in this case in a ready to drink version, in a canned beverage, and within 10 to 20 minutes you have pretty high levels of blood ketones.

Now where I’ve noticed this is most beneficial, since I’ve been able to use these for many months now, I find it best if I’m more on the fatigued side. Maybe my sleep isn’t very good or my stress is real high. And I have noticed that a higher dose at two cans, which is going to be about 20 grams of ketones on days.

I thought we’re going to be a throwaway session, especially for grip training. I’ve had two cans of the Tecton ketones and more often than not, the session’s been pretty darn good. I don’t know really why that is. I think there’s maybe some central nervous system effect. We do know that in a fatigued state ketones can cross the blood brain barrier.

And may serve as a alternate fuel in the brain. So I’m not really sure why that effect seems to happen. But it’s happened to me multiple times. So you can check them out and go to the link below. Full disclosure, I am a scientific advisor to them and I am an ambassador. So I am probably biased that direction.

The great part is that they taste quite good actually. A lot of the ketones, especially the exogenous ketones, the esters on the market in this case, they do not taste well. But in this case they do. They use a different ketone ester. It is a BHB molecule bonded to glycerol, which is different than all the other products on the market.

So check them out. I’ve got a discount code below for that. Also. Thank you so much for listening to the podcast. Really appreciate it. And check out this full podcast here, all about strength with my buddy, Paul.

[00:03:44] Dr Mike T Nelson: Welcome to the podcast. Really appreciate it.

[00:03:47] Paul Oneid: Thanks, man. Thank you for having me.

[00:03:49] Dr Mike T Nelson: Well, thank you. This will be fun. We had a good chat a couple months ago in person, which was great in the Virginia, Washington DC area. And one of my main questions I have is how do you define strength?

And then what would be the best way to develop it?

[00:04:10] Paul Oneid: That’s a fantastic question. So

[00:04:11] Dr Mike T Nelson: I’ll start with the easy ones.

[00:04:13] Paul Oneid: Yeah, exactly. Let’s just dive right into it.

[00:04:15] Dr Mike T Nelson: I

[00:04:16] Paul Oneid: think I look at strength very much the same way as a basketball player would look at a free throw. Strength to me as a skill and a skill needs to be specific to the task.

So when we’re talking about strength. In general, it’s very challenging to define. I would define it as your ability to perform a high rate of work on a given task. And the rate of work could be repetitions, it could be absolute load. You would have to define that within the question. I compete in powerlifting.

Most of the athletes that I compete in are performance athletes. So a lot of what we look at is one repetition, one repetition maximum. We look at bar velocity. We look at box jump height or vertical jump height. And we try to have some sort of objective measure to compare against. That’s how I would define strength as a skill specific measurement of output.

How do you build it? You got to shoot your free throws. You got to practice. And this is, I got to

[00:05:19] Dr Mike T Nelson: do the thing. You got to do

[00:05:20] Paul Oneid: the thing. And this is something where I find it so fascinating. how the human body can be so variable. Case in point, I have many of my athletes need regular exposures to high intensity, single effort lifts in order to progress their strength.

They need to continuously have exposures to that maximal specific output. I have some of my athletes that never lift above 80%, maybe 85 until they’re on the platform. It’s just seems

[00:05:57] Dr Mike T Nelson: like a low percentage. I wouldn’t have guessed that

[00:06:00] Paul Oneid: I’m actually one of those lifters. Yeah, I don’t need to, I don’t need to hit anything above an RP eight, seven and a half, eight in training to be able to peak my strength.

I have a few theories about why that is. I think for myself, I don’t, and if those athletes that I have who don’t need to lift so maximally is they’re very type two oriented. So they’re, I definitely do

[00:06:27] Dr Mike T Nelson: fiber oriented, right? Just like to

[00:06:28] Paul Oneid: fiber oriented. So like they’re just very explosive and those high output singles will say above 90 percent are incredibly fatiguing to them.

So they have this depressed central nervous system activity afterwards for multiple weeks. So if you would ask them to do these regular exposures. They have a very quick degradation of performance. And these are things that we test over time. These are things that we look at within the training protocol to say, All right, let’s track your progress doing this sort of iteration on training.

Let’s track your progress doing this. And let’s see which sort of interventions work the best. And. That’s why you’ve got to treat every athlete like an N of one. But the big thing is practicing the skill. So even though these athletes may not be lifting maximal specific maximal attempts, they’re still practicing the skill associated.

So squat bench deadlift or lean snatch or even, whatever special exercises we deem appropriate for Our athlete populations, they’re still practicing them. We’re still focusing on skill of execution, and we’re focused on maintaining bar velocity. And all we try to do when we go for that heavy single.

In the competition is we taper volume. The same thing happens if you’re having regular exposures to high effort singles, instead of tapering volume, because your volume is already low, you just taper intensity. But the reason I find it so fascinating is that interplay between volume intensity, and then you also add in frequency of exposure.

It becomes a really cool game of push and pull to see how to get the best performance on a given day. That was a very long winded response.

[00:08:17] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, that’s great. Some of the specifics I’m curious, I’m sure other people have questions. How long do you typically run your tapers? Like in my experience, I think one of my biggest mistakes was, especially with Strongman and especially a handful of powerlifters I’ve coached, I ran their taper too short.

And I screwed up some people, which was my fault. And then I think I went a little

[00:08:44] Paul Oneid: I find this to be highly dependent on a few factors. The first one being absolute strength level. So the stronger an athlete is at an absolute level. So if you’re comparing their lifts to like the limit lifts in their weight class. The stronger they are relative to body weight, the longer their taper will be.

So personally, I squatted for 800 pounds. My tapers four weeks long.

[00:09:10] Dr Mike T Nelson: Wow. That’s so long, but it makes sense though.

[00:09:12] Paul Oneid: Yeah. So I’ll have, I also only squat once every 10 days.

[00:09:17] Dr Mike T Nelson: That’s so crazy.

[00:09:18] Paul Oneid: Yeah. I’m also 37 years old. I’ve been competing for home and 12 years. No, 17 years. I did my first meet when I was 20.

So I have a high training age, high output capacity, and my workload outside the gym is very high. So fine, every 10 days is money for me. Four week taper. I have another one of my athletes, she’s a 123 pound female, deadlifts well over 400 pounds.

[00:09:46] Dr Mike T Nelson: Damn!

[00:09:47] Paul Oneid: Her taper for the deadlift is three weeks long, her taper for the bench is 10 days long.

So I tend to look at, what her performance is on a week to week basis on a given lift, what week in relation to her heaviest set, we see the kind of rebound effect, that’s super compensation that we’re looking for. And then, so I mentioned absolute strength level relative to body weight, Also that body weight in general.

So a larger mammal, as we like to say, their fitness level is quite poor in general. Like you have the rare, like I have a lifter, he’s 285 pounds with abs. The guy’s a freak. He’s has a high fitness level. So his taper doesn’t have to be as long. I have another lifter who’s about 303. His tapers are much longer because his fitness level.

Is much more poor. I find the higher the fitness level, the quicker that fitness degrades without exposure. The next factor that I find to be incredibly important is whether or not the lifter is enhanced. When you have an enhanced lifter, there are neurological effects of performance enhancing drugs.

Those neurological effects tend to allow you to taper longer and have a much higher super compensation effects. So the fitness doesn’t degrade as fast. You accumulate fitness much faster, which means you accumulate fatigue much faster, which means you have to offload more fatigue so you can. Display strength with natural lifters.

They need a closer exposure to that maximal lift, and that doesn’t need to be. It doesn’t need to be a maximal attempt, but they do need to lift a little bit heavier throughout that taper. So yeah, depends.

[00:11:39] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. No that’s great. Cause I think if I were to go back and do it again, like you said, I, cause the one thing as I was thinking about this in hindsight is exactly what you said, especially for smaller lifters.

There’s a bigger discrepancy between their bench press, their deadlift and their squat. Just in terms of sheer numbers. And I know you’re loading different tissue and all that stuff. And one’s axial. And I get it. When you’ve worked with lifters long enough, you’ll see that some lifts, they can progress real fast, real easy.

You can just beat the shit out of them with frequency. Other lifts, you just can’t. And it could be like the same lifter, right? You’re not comparing two people, different lifestyles, different genetics, whatever. So I think what you said is I would have a taper for their bench press or squat and their deadlift.

I would try to look at those differently throughout training. So then when it comes time to taper, those may end up being different time points instead of what I did in the past was always just lump them in all together because, well, they’re doing them all in one day.

[00:12:41] Paul Oneid: Yeah. And depending on how you organize the training, you may have an SBD day where you do squat bench and deadlift.

Oh, sure. Again, I find larger lifters just can’t do that. That day would be four hours long. This is where it plays in with like practicality, like even myself when I’m squatting, like if I have to work up to 800 pounds, it’s taking me 90 minutes just to work up to that 800 pounds.

[00:13:04] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah.

[00:13:05] Paul Oneid: Then if I have to deadlift after that and I’m going to get 700 pounds, well, it’s going to take me another, 60 minutes to do that. Now we’re at a two and a half hour session, not including a warmup. It’s just not feasible within the schedule. So it’s like what’s ideal versus what’s practical. But I agree with you having.

Taper lengths vary per lift. Okay, here’s an interesting conversation. I find anthropometrics play a really big role here. So if you have a lifter, long limbed, short torso, fantastic deadlift leverages, they’re going to be able to, one, handle more volume, two, handle more frequency, and three, they likely won’t have to taper very long because the deadlift is just something they move very efficiently.

If you have that same lifter squatting, they’re Their squats going to tank really quickly and you’re not going to be able to handle as much volume. You’re not going to be able to handle as much frequency because they’re in that like almost good morning hinged over position just to hit depth.

[00:14:12] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. The long, I have long femurs and squatting sucks because it’s no matter how far I push my toes in front, which is a whole nother conversation. Yeah. If your femurs are frigging long. There’s only so many ways you’re going to go.

[00:14:26] Paul Oneid: Yeah. Like for me, I have very short femurs. I have a relatively like a moderate wide stance.

I’m pretty upright. Squatting doesn’t really beat up my central nervous system unless I’m squatting in wraps and then. That’s another whole other ideal because you’re lifting super maximal weights. But deadlifting beats me up because I have a long torso add to that my deadlift technique.

I actually, I’ll purposefully round my upper back

[00:14:54] Dr Mike T Nelson: to

[00:14:55] Paul Oneid: get my hips closer to the bar. Well, that’s going to place more axial load, more sheer on the spine. So it takes me a little bit longer to recover from deadlifting. So my deadlift taper, I think it’s probably because I’m squatting and wraps, it’ll probably be about the same as my squat, but maybe three or four days longer.

I’m actually getting ready to peak right now. So next week on Thursday, I’ll take my heaviest squat and then about four days later, maybe five days later, I’ll take my heaviest deadlift, but that deadlift will not be a maximal deadlift. It’ll be something in 90 percent range. Cause I, I find for me, if I can hit a really smooth 90 percent single

[00:15:41] Dr Mike T Nelson: you’re good for more,

[00:15:42] Paul Oneid: I peak really well into the meat.

So my goal for this meets to pull somewhere North of 700. So I’ll go in and pull 300 or 305 and I’ll be good.

[00:15:51] Dr Mike T Nelson: Kilos. I was like, wait a minute, what happened there?

[00:15:54] Paul Oneid: So something north of 320, probably in the neighborhood of a 330. So I’ll go in and pull 305, try to smoke it and then taper into the meat.

[00:16:05] Dr Mike T Nelson: Nice. And when you’re tapering, do you use any outside metrics to adjust it? What I ended up doing is I ended up I got a fair amount of clients this way by using HRV. And the people I got as clients historically had a horrible taper. It was like, For probably a five year period, it was like the same storybook thing of, Man, all my lifts in the gym are great, I’ve hit these numbers in the platform in the past, I had this awesome training cycle, and then, I just shit the bed on the meat.

And then next year, the same thing happened. And we looked at their taper, and one guy was tapering for five days. And I’m like, I highly doubt you’re ready. And so we started at two weeks and we watched their HRV. And it wasn’t until a couple of days before the meet and we severely, hacked out volume, just did a little bit of intensity stuff that they actually were, in my opinion, Ready to go.

[00:16:58] Paul Oneid: I don’t tend to use HRV. Okay. So here’s a personal bias of mine. I just really don’t like a lot of these metrics. Cause I think the nocebo effect of them messes with too many people.

[00:17:10] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, I definitely can. A hundred percent.

[00:17:12] Paul Oneid: I would be one of those people’s number, like case in point this morning, my workload has been very high.

We’ve traveled, I’ve traveled literally every other week or every week since April. No

[00:17:25] Dr Mike T Nelson: damn

[00:17:26] Paul Oneid: crazy.

[00:17:26] Dr Mike T Nelson: That was more than me, I think.

[00:17:28] Paul Oneid: Yeah. And so the last weekend, my wife won her pro card and bodybuilding, which was, yeah, congrats. Thank you. So it was like a huge emotional high came down this week. My workload has been high.

I’m like, Last night I’m I need some sleep. I have a big bench workout Friday. I get in bed 9pm like sick gonna get eight hours of sleep. Awesome. Thunderstorm, power outage, CPAP can’t be used.

[00:17:53] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh no.

[00:17:54] Paul Oneid: So I slept three hours.

[00:17:56] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh.

[00:17:57] Paul Oneid: Guess what? Had a phenomenal bench day today.

[00:18:00] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, that can happen.

[00:18:02] Paul Oneid: Had I looked at my, I guarantee you my HRV was horrendous this morning.

[00:18:08] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh yeah.

[00:18:10] Paul Oneid: But I didn’t look at it. I just went in and I took the training for what it was. And part of the reason why I don’t like these things is, are you going to delay the competition? Hey guys, today, HRV is really bad. I’m going to wait till tomorrow. You guys come back tomorrow. I’ll lift. No, you’re not.

So there’s a little bit of old school mentality there for me of you have to show up on the day to do what is required. But I do definitely value that secondary input that can be used. And we do track HRV indirectly with, so usually if an athlete has an eyewatch or something like that, we’ll use the metric from HRV cause we use coach catalyst.

So it’ll pull that right from the Apple health app. So I’ll look at it. I actually find personally that resting heart rates a better variable to look at. It’s more indicative for me.

[00:19:02] Dr Mike T Nelson: On most wearables. I would agree with that. Cause I don’t, Like how they do HRV, but yeah, I would agree.

[00:19:08] Paul Oneid: So I’ll look at resting heart rate.

I’ll look at HRV and what I might do is I may adjust the taper in terms of, I might pull volume earlier. I may keep it in longer depending on what I’m seeing, but I won’t necessarily change the length of the taper and I won’t really tell the athlete what I’m doing or why I’m doing it

[00:19:30] Dr Mike T Nelson: because I don’t

[00:19:30] Paul Oneid: want them to realize.

Either they’re in a good spot or they’re in a bad spot. It’s Hey, you just focus on doing what you’re doing.

[00:19:39] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. I actually agree with all that. Which it seems like on paper would be diametrically opposed, but, and that’s one of the, probably the most common emails I get from people is, well, why use an HRV?

What if they show red day before a competition, they’re going to take their whole competition for it. And I’m like. If that happens, you as a coach screwed up. One, you let them put too much faith in the data, you let them look at it too much and guide their own training. Four, you didn’t educate them properly.

Three, you should have thought far enough ahead to know that almost every, even experienced athletes are going to be massively sympathetic before a big competition. It’s the rare people that sleep well and have all these things to go well. That’s, in my experience, a rare exception. So you should plan for it.

And like you said, I like looking at it in terms of a physiologically peak under the hood as to what’s going on.

[00:20:33] Paul Oneid: Yeah.

[00:20:33] Dr Mike T Nelson: And, once we’ve decided on the length of taper, I typically don’t change that because you have to perform on That’s just the way it is. But like you said, I will pull volume or, okay, let’s only do, two attempts today above 90 percent instead of three or one, or let’s drop it to 85 percent or, and I just tell them outright Hey, We’re going to use HRV.

I’m going to be looking at all your stuff. I’m going to talk to you and your taper is going to be relatively fluid and we want to just give you the stress you need to hold those strength qualities, but we want to get rid of as much fatigue as possible. And usually then they’re Oh, okay.

That kind of makes sense.

[00:21:11] Paul Oneid: Yeah. It’s a very delicate dance and you know what? Yeah. It’s more of an

[00:21:15] Dr Mike T Nelson: art almost.

[00:21:16] Paul Oneid: Oh, for sure. And that’s actually one of my, one of my favorite quotes is like training is as much art as it is science because research and data is always going to be contextually dependent and it’s how you personally artfully apply the research and data to the intervention that’s going to dictate the response of the individual.

So if you’re too swung onto one side of the pendulum, either way, you’re going to run into problems. And usually the problem is the psychology of the athlete. That’s always the bottleneck. And again, this is another reason why I harp so much on that coach athlete relationship and making sure that there is trust in that where the athlete like implicitly trusts you because you have shown them over time, the evidence that you are caring for them, both through the language that you use and the way that you modify and adapt their training as needed.

I’ve had so many instances where great example. So I have an athlete. She competed probably a month and a half ago. Her training cycle in her mind was horrendous. She also deals with depression. So if you are looking at life through this gray lens and everything is shaded gray, not 50 shades of gray, just gray.

It’s up to you as the coach to objectify the data and make sure they understand. No, we’re in a good place, but she wasn’t hearing it. We ended up keeping intensity up a little bit longer. We ended up doing a few things different than her past tapers. Was that. strategy dictated by the data I was accumulating during the training cycle?

Absolutely not. What it was dictated by is the need for her to feel confident stepping on the platform. So we were able to build that confidence. It shortened her taper a little bit, but she went into the meet feeling like she had stacked a few wins in the two weeks prior. And she had a phenomenal week.

She meet, she went eight for nine.

[00:23:30] Dr Mike T Nelson: Nice. That’s amazing.

[00:23:31] Paul Oneid: She had a state record deadlift. She won the meet PR squat and a PR competition bench. So for all intents and purposes, it was a fantastic meet. Obviously, she’s I could have done better if my, whatever, yeah, maybe, but now you get to go live your life and we get to recycle training and you get to do some stuff that you like doing.

So win.

[00:23:54] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. And I think that’s always, that’s where the art comes in. I have a term I coined, which I just call coaching leverage, which is the physiologic response times the psychology of the person or in the terms of habit change, like the client’s ability to change. But it’s basically.

The physiology times the psychology. Both of those add up to your result because as like You could have an on quote paper, perfect taper, but if the athlete doesn’t think this is going to work, is not convinced, hates it is, their mood is bad, they don’t want to train, it’s okay, so, that better be one hell of a huge physiologic lever you just pulled, and most likely it’s not, so, maybe you give up a little bit on the perfect scenario, and you rig the psychology in their favor, so, They want to train.

They feel confident. Oh man, I just destroyed my opening lifts in the gym, and I’ve only got five days to go. And, like, all those things make such a huge difference. Even if you can’t, quote, put them on paper or give them a number.

[00:24:57] Paul Oneid: Yep, for sure. I couldn’t agree more.

[00:25:00] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, and I think, and I know I got hung up too early in my career on just, well, what is the physiology?

Right. And then you start coaching people and you realize exercise physiology, man, I picked the wrong field. I should have been a fricking psychologist, like almost none of this has to do with exercise physiology. It’s yeah, you need to know it. But like in practice, like knowing psychology and I went back to study neurobiology instead, that makes such a huge difference because that gives you a little bit of leverage around the art portion of it.

[00:25:31] Paul Oneid: Absolutely. I think most coaches focus way too heavily on the X’s and O’s, and they forget that they’re actually just coaching a person. And as soon as you start speaking to the person like they’re a person, so many more doors open up. I always, we say like the physiology only matters as much as the psychology allows.

[00:25:53] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, I love that.

[00:25:54] Paul Oneid: If you can’t, if you can’t coach the individual and you keep trying to coach a program, You will fail not to mention, you’re not going to retain any of your clients. Cause they’ll think you’re a

[00:26:05] Dr Mike T Nelson: God. No.

[00:26:08] Paul Oneid: Yeah.

[00:26:09] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And even if their HRV was wonky in the past, I’d be like, Oh, it looks like your sleep was like 2.

8 hours less than this and that. And now I just literally send them a note, probably 90 percent of the time, especially if it’s the first instance. And I don’t really know them all that well. I’m just like. Hey, man, looks like you’re pretty stressed. What’s going on?

[00:26:28] Paul Oneid: Yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know how that works.

How are you feeling?

[00:26:32] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And are, how are you feeling? And that’s it. I don’t say anything else. And it’s crazy. Sometimes the responses you get back that they didn’t tell you. I had one people, one person is Oh yeah, I started treatment for cancer. It’s what the fuck? That might be important for me to know about your training, but he’s I don’t want to make a big deal out of it.

And they’re like, holy shit.

[00:26:51] Paul Oneid: I don’t want to make a big deal out of cancer.

[00:26:54] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Okay.

[00:26:56] Paul Oneid: Okay.

[00:27:00] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh man. Related to tapering, this is an idea I’ve probably thought too much about. Do you think there is such a thing as super compensation, i. e. going above baseline? Or is that a training adaptation that we could not see before because there’s too much fatigue in the system?

[00:27:23] Paul Oneid: I think it’s the latter.

So yeah. I don’t think that you’re actually going to be stronger than you’ve, you were in general

[00:27:33] Dr Mike T Nelson: on

[00:27:33] Paul Oneid: day, but what we are doing is we’re decaying fatigue to a point where we can display the strength that we’ve accumulated. And I think that’s where a lot of people miss. So if you see. A lifter who perpetually underperforms their gym lifts on the platform, it’s because they were either lifting too heavy in training or doing too much volume in their taper to be able to decay that fatigue.

A lot of that has to do with, coming back to psychology, a lot of that has to do with insecurity. You have to be okay to detrain slightly because if you decay fatigue, you will decay some fitness. Thanks. But you need to display the strength that you’ve accumulated. And I think there’s a lot of factors that go into that.

Especially once you add performance enhancing drugs, because of that neurological effect, I think when you introduce performance enhancing drugs, that effect is magnified. So you’ll see lifters, probably in the 107, 110%. At the meet versus training. Whereas if you’re a natural lifter, it might be like one Oh two, one Oh four.

The other thing you have to look at is like your attempt selection. I think a lot of people just perpetually choose attempts that are too heavy because they’re expecting this massive effect of a taper. And it might only be two to 4%, but you should be outperforming your training on the platform. If you taper properly,

[00:29:09] Dr Mike T Nelson: you find people just take their opener way too heavy. Okay. I don’t see that as much as I did many years ago. It still happens. Yeah. And I’m thinking like what are you thinking? Because for listeners, right. If you bomb out of the squat, like you don’t get to bench or demo.

[00:29:25] Paul Oneid: Yeah. I think opening too heavy again, it comes down to insecurity.

It also comes down to a lack of maturity on the part of the lifter and education on the part of the coach, educating the lifter because no one cares what you open at. So if you open at the same weight, three meets in a row, but you perpetually PR that lift every meet who fucking cares what you open at.

I remember the meat where the meat in 2015, when I squatted 800 for the first time I opened at seven, I made 50 pound jumps per attempt.

[00:29:59] Dr Mike T Nelson: Wow.

[00:30:00] Paul Oneid: I was like, whatever. When I pulled three 30, I opened at, I think two 85.

[00:30:10] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh wow.

[00:30:11] Paul Oneid: So 45 kilos, your opener doesn’t matter. It’s just, it’s a stepping stone.

I actually would consider your opener to be like your last warmup. You just platform. And then, that second attempt somewhere in the neighborhood of 95 to 97 percent of whatever you hit in training. And then 102, 105, somewhere in there for your third attempt, depending on how that second attempt goes.

And I think having a great plan, I like to look at my meat plans for my athletes is like a pick your own adventure. So we know what the opener is going to be. Then we have, based on how that feels, you have three choices on your second attempt based on that second attempt and how that feels. You have three choices for your third attempt.

Assuming everything goes well while you pick your own adventure, you stay on the right side of that snake or that, that web, whatever you want to call it. And you end up best case scenario, third attempt, huge PR worst case. If you plan it appropriately, you still get a small PR. And you go three for three.

I don’t, I really don’t like this notion that if you’re going nine for nine, you’re not trying hard enough. The goal is to accumulate the largest total.

[00:31:27] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. The goal is to make the last lift.

[00:31:30] Paul Oneid: The goal is, the goal is to lift the heaviest weight possible on the day. And if the heaviest weight possible on the day was maybe a little bit higher than what you ended up choosing, but the accumulation of effort for the day is higher than you’ve ever done.

Yeah. The total PR is what matters. Yeah. Yeah. So if you don’t PR any of your lifts, but you PR your total, well, congratulations, you just made progress. So the, and then this is where like you could, you have to address the psychology lifter. Like I personally, if I PR my total, but I don’t PR any of my lifts, I personally would consider that a failure.

I’m also at a point where if I don’t PR any of my lifts, I’m not going to PR my total. So there’s also that but there, there’s going to be a scenario Maybe I PR my squat big time, but it takes away from my bench and then I’m fatigued going into my deadlift. So I can’t PR those lifts.

And this is where, again, planning on the part of the coach to identify the needs of the lifter on a given day, how to choose those attempts based on how they, the subjective feeling. And another thing that I love doing. On third attempts, especially if I’m coaching at the meet on the day with the lifter is allowing them to pick their third attempts.

It’s something. And I say I frame it as, you’re going to choose the weight. You’re going to put the weight on the bar and you’re going to lift it. So you better choose wisely.

[00:32:58] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. No

[00:33:00] Paul Oneid: matter what, it’s a win situation because if they go too heavy, they learn humility. If they go too light, well, they have a lot of motivation for that next meet.

And if they go, if they choose a really appropriate attempt. They feel more self efficacy about their ability to own their performance. So no matter what the outcome, whether it’s a successful lift or a missed lift, they’re going to win in the long run. And that’s all we’re trying to do. Most of 99.

99999 percent of the lifters that you coach, it’s not going to be their last meet. And if it is for whatever reason, well, they should have some autonomy in the process.

[00:33:43] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, I like that. And then even on the physiology side, like they have more data than you’ll ever have. Like they’re the ones living in their body.

They’re the ones who did all the damn lifts. And if you, and I’ve made this mistake before I’ve watched the lift and went, damn, that was fast. How’d it feel like, dude, it felt horrible. I’m only going up a little bit and I’m like, really? And then, yep, that was the right choice for them. Like I should have listened to them and not just watched it and judged it off of speed.

And then you think back to, oh yeah, almost all their trainings, like they were never. A slow grinder, lifty person, like if they would either hit something or they would miss it, there’s just maybe the way they’re wired or whatever. So why would meet day be any, really that different?

[00:34:25] Paul Oneid: Yeah, I’m I’ve had so I’ve coached so many lifters in competition that I can probably look at the way someone approaches the bar.

And tell you if they’re going to make it or miss just based on the way they approach the bar. It’s a game that I like to play with my wife whenever we’re watching meets.

[00:34:43] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yep. I do the same thing.

[00:34:45] Paul Oneid: But that’s going to, that they’re going to miss. And then we’ll make bets on dinner. Usually I get dinner paid for.

[00:34:52] Dr Mike T Nelson: Nice. What do you look for in that?

[00:34:56] Paul Oneid: First, I look at the lifters eyes. If they’re looking anywhere other than the barbell, they’re probably not very confident. The next is I look at body language. If they are trying to hype themselves up more than they have tried to hype themselves up prior to that lift, they’re probably gonna miss the next is the way they approach the setup for the barbell.

I like to preach that your setup should be robotic from set, from empty bar to pr. The way you approach the bar should be exactly the same, right? We’re shooting free throws. There’s any deviation in that, the chances of you, number one, it’s going to fuck with your head. So if you run up to the bar out of control, maybe your shin hits it.

We’re talking about a deadlift. Like your shin hits the bar, it rolls around, you’re going to miss 100%. Very rarely will you have that person with the mental fortitude to gather themselves, reset. But most of the time that’ll throw them off. If you see a lifter, they’re looking at the bar.

Their demeanor is confident, like proud posture. Their arousal level is consistent throughout the day. Their setup looks robotic. They’re going to hit the lift for sure.

[00:36:16] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. It’s wild to me how variable setups would be even in, I wouldn’t say at the highest level, but even at a moderate level, because to me, it’s like, it goes back to as a coach, like controlling the things that are controllable, like I’m real big on for if it’s strongman, CrossFit, whatever, like your conditioning should never cost you anything, because to me, If we do it intelligently and I’ve got six to eight months, unless it’s like an elite level world class thing, you should be good enough in that because it’s a trainable thing.

Like you should have enough reps where you know what your form is, each individual step. And you should, whether that’s the best form for you or not, it’s a different discussion. But you should be able to execute that every day because that is 100 percent within your control.

[00:37:04] Paul Oneid: Yeah. And at the end of the day, if you chose the load, it’s on your shoulders, man literally, it could be on the squat

[00:37:12] Dr Mike T Nelson: on your shoulders.

[00:37:13] Paul Oneid: So I personally, I’m not loading anything. I know I can’t hit, especially at my age. I’m not like, we’re not throwing Hail Marys right now. We’re hitting

[00:37:24] Dr Mike T Nelson: bullets.

[00:37:27] Paul Oneid: So I just, I try to, educate my lifters and to allow them to have the autonomy to make good choices and live and die by those choices.

It’s you can, I’m very proud of the fact that if you go to a meet and you see any of my lifters, you can tell they’re my lifters by the way they carry themselves. And I’ve been told that on a number of occasions. So. I’m doing a good job with it, but it’s just because they’ve done it before in their head.

They’ve done it a million times before they’ve done the visualization that they’ve done. They’ve done the mental reps. So when they go up for that PR, they’ve already lifted it a thousand times in their head. Just got to do it again.

[00:38:11] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. What about this? I’ll throw a bro phrase at you and you tell me your opinion.

It takes mass to move mass.

[00:38:25] Paul Oneid: This is a conversation I’ve had so many times. My former business partner, Tony Montgomery, he’s currently doing his his PhD at Oklahoma state.

[00:38:35] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, cool.

[00:38:36] Paul Oneid: Incredibly intelligent human being. He and I would fight about this all the time.

[00:38:42] Dr Mike T Nelson: I did not know this. This is good.

[00:38:43] Paul Oneid: Yeah. So the lifter with the most muscle will tend to be the strongest.

When you factor in body weight, so we’ll say muscle mass, fat mass, just mass in general. When you look at the totals across weight classes, there’s a linear trajectory. The heaviest people lift the most weight. You can boil that down to surface area. So if you have a larger surface area, there’s more surface area to distribute.

Yeah. load. So every square inch of surface area has to carry less load. Then you look at, joint size as you increase the ability to stack tissue under a barbell, leverages increasing to a point, right? So you’ll usually see the biggest deadlifts in the 242 to 275 weight class, 308 supers, their deadlifts suck because they have huge guts.

[00:39:36] Dr Mike T Nelson: Is that a mechanics issue though, at that point?

[00:39:39] Paul Oneid: It’s just a size issue. There’s just too much body to get the hips close to the bar.

[00:39:44] Dr Mike T Nelson: Right. So the their belly is in influencing their best mechanics.

[00:39:49] Paul Oneid: Right. But their squats are the heaviest.

[00:39:51] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Squats are huge.

[00:39:52] Paul Oneid: Because that core is just so large.

[00:39:55] Dr Mike T Nelson: Big

[00:39:55] Paul Oneid: base. Bench presses, same thing, thicker human being, shorter bar path, super heavyweights are going to have the biggest bench presses. So when you take that leverage into account, but let’s talk like body weight specific, the lifter with the most muscle mass within a certain category will tend to be the strongest.

And you say, okay, what about those lifters who are super light, but very strong? John hack, for example, competes 98 class will routinely smash super heavyweights. Dude, squats over 800 in sleeves. Deadlifts over 900 I Oh

[00:40:33] Dr Mike T Nelson: Jesus.

[00:40:35] Paul Oneid: One of the great 1

[00:40:35] Dr Mike T Nelson: 98 pounds. Yeah. One

[00:40:36] Paul Oneid: of the, one of the greatest strength athletes of all time.

[00:40:39] Dr Mike T Nelson: Crazy.

[00:40:40] Paul Oneid: He’s an N of one you cannot make. Yeah. He is a freak. . You cannot make a rule based on the out, so let’s throw that out. He’s also one, he’s also max out the weight class, like he walks around over two 20 and competes at 1 98. Now throw out the N of one. You look at the research, well, the research would dictate the muscle cross sectional area does not, and hypertrophy does not correlate with maximal strength.

I do not disagree with the research at all, but we have to look at the limitations of the research within most of these studies. They’re comparing within a training period of at most 12 to 16 weeks to make a meaningful improvement in hypertrophy in 12 to 16 weeks. I’m going to, I’m going to put my money on it that you’re not going to put on a lot of muscle in 12 to 16 weeks without putting on a ton of body weight.

You’re also going to accumulate strength very quickly because it’s a neurological adaptation. So, of course, you’re going to get stronger within 12 to 16 weeks than you are to hypertrophy. So for making correlations, it doesn’t make sense. But if I take a lifter and I add 10 pounds of muscle to their frame, Yeah.

And then I allowed that 10 pounds of muscle to be trained to be neurologically efficient over time. That’s going to be a stronger lifter, hands down. The long game is where this is important. So if you are someone who is hell bent on staying in the same weight class, you’re probably going to hypertrophy by virtue of just training, right?

Just being in the gym, being strong. So you’ll recomp to some degree at the same body weight. But if you’re having more frequent exposures to high intensity activities. you’re going to get stronger than someone who is focused exclusively on hypertrophy. My bias is towards more of a concurrent approach where we will favor strength adaptations on our main lifts and then tailor the assistance work towards hypertrophy.

You’re not really going to have any interference effect because hypertrophy work will make you stronger and strength work will hypertrophy you to some degree if volume is meaningful. And You do that for a really long time. It doesn’t have to be more complicated than that. And that is my personal bias.

So in the conversation of mass moves, mass, yes, but. So there has to be that contextual understanding of the situation. Larger lifters have higher totals. So if we’re measuring just based on the total lifted, yes, absolutely. Bigger mass moves mass. But if you get so big to the point where you can’t deadlift.

You’re going to have to make sure that your squat and bench are huge. And that’s usually what happens. That’s the reason why John Hack is winning all these meets because the meets are based off of a coefficient. The coefficient does bias that more middleweight lifter just by virtue of the coefficient, whether you’re using IPF points, dots.

Wilkes, whatever it might be. I don’t fucking if you’re totaling 2, 400 hit raw, like you’re fucking strong. So

[00:44:15] Dr Mike T Nelson: I had a body under 200.

[00:44:17] Paul Oneid: Well, I think his best total somewhere in the neighborhood of a thousand 50 kilos.

[00:44:22] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh geez.

[00:44:24] Paul Oneid: Yeah. So he’s in the neighborhood of that 22, 23, a

[00:44:26] Dr Mike T Nelson: lot of stuff there.

[00:44:27] Paul Oneid: Well, cause he went 800 on the squat. He went nine 38 on the deadlift. So right there, you’re already at 1738 and then he benches close to 600

[00:44:39] Dr Mike T Nelson: and that’s wild.

[00:44:42] Paul Oneid: It’s ridiculous. It’s really crazy. And there’s a number, like there’s a number of guys, Dan Griggs, for example, he deadlifts over a thousand in a full meet.

[00:44:53] Dr Mike T Nelson: I am,

[00:44:54] Paul Oneid: but he, I’m going to say this and I’m speaking in relative terms, his squats horrendous. So is his bench press.

[00:45:02] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. So do you know his numbers in those or his

[00:45:05] Paul Oneid: squat, his squats in the mid sevens and his bench presses in the mid fours. So he can make up for it because he deadlifts a thousand pounds.

[00:45:14] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah.

[00:45:17] Paul Oneid: But this is why you play the game of building the total. So if I was Dan Griggs, which I’m not, and I never will be, I probably wouldn’t push my deadlift much at all in training.

[00:45:27] Dr Mike T Nelson: No. I

[00:45:28] Paul Oneid: would prioritize the other two lifts. But what we’re seeing these days with the rise of social media is, well, he has to deadlift because that’s what he’s known for and that’s what’s building his brand and that’s what’s building his awareness.

I’m not sure if him in specific, I don’t know if he’s monetized his personality, a guy like Jamal Browner, for example he even competed at giants live now. So, and this is a two 42 lit power lifter deadlifts close to a thousand. It’s wild,

[00:46:03] Dr Mike T Nelson: but

[00:46:03] Paul Oneid: Jamal Brown or sorry to interrupt you Jamal Brown or pulls close to a thousand.

He squats over 800 and benches up around five. Exactly.

[00:46:12] Dr Mike T Nelson: It’s crazy. So nuts. Yeah. I just had the flashbacks to the, I think it was a giants live or Eddie Hall pulled over a thousand and looked like he was going to die.

[00:46:21] Paul Oneid: Yeah. 500 kilos.

[00:46:23] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. You’re watching it. And I, I took all the time out. I watched it live and I’m, And on one hand, you’re like, that’s impressive.

On the other hand, you’re like, I think he’s going to die. Like I literally, I think he’s not going to make it to see tomorrow. He looks so rough.

[00:46:44] Paul Oneid: I would love to see a study and look at like blood pressures under that type of load.

[00:46:52] Dr Mike T Nelson: Gotta be just crazy. Like the only studies I can think of are usually like press studies, but

[00:46:57] Paul Oneid: I don’t want to know mine.

I don’t want to know. But I can tell you like being on, I think the heaviest squat I’ve ever taken in a gym was 850 pounds and standing up with 850 pounds on your back. You feel like you’re going to die. It feels great when you stand up, but you feel like you’re going to die.

[00:47:16] Dr Mike T Nelson: Just the, I don’t think people who, the heaviest I’ve ever done is.

I’ve done like 500 pound deadlift, and the heaviest I’ve had to actually was probably a yoke. It was probably only 450, 500, or something like that. And I, it was the first time I ever trained it. And you think, yeah, it can’t be that bad. And you get under it. And I’m like, this feels way worse than I thought it was going to feel like I’ve deadlifted this much, but to have it on my back and then try to move with it.

I was like, and this is like half of a thousand pounds and these crazy numbers people are doing. It’s so bonkers.

[00:47:52] Paul Oneid: Ridiculous. So I have a tremendous amount of respect for any, anyone willing to push their body to that limit. And I find it incredibly fascinating. I find the Here’s the other thing. When you’re talking about loads that are, that absolutely heavy, there are no rules, , right?

And I’m being serious. Yeah. No, there is no research. There is no study, there are no rules. Which begs the question that I get asked all the time is ’cause I work with a lot of coaches, is, does my coach need to be strong in order to help me be strong?

,

my answer is no to a point.

[00:48:33] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah,

[00:48:34] Paul Oneid: because at some point, if your coach hasn’t squatted over 800 deadlifted over 700, they don’t know how that feels or what it takes to get there. So they’re not going to know you can’t program the same way for somebody trying to go from 500 to 600 as you can try to go from 600 to 700 or from 700 to 800, which is why you see the frequency for these.

More absolutely strong individuals drops off a cliff, relative intensity drops off a cliff. Cause even if you’re talking about like you take someone like well, it’s just, let’s just use a Dan Griggs, a thousand pound deadlift, Dan, go hit an RP six single on the deadlift. It’s going to be probably 700 to 800 pounds.

[00:49:30] Dr Mike T Nelson: So crazy.

[00:49:31] Paul Oneid: Which is wild.

[00:49:32] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah.

[00:49:33] Paul Oneid: You have to look at that load on a human body. That RPE6 single for Dan is going to be far more fatiguing. Then an RP six single when the absolute load is 250 pounds. So the volume, and this is where the art and science gets so fascinating to me. I did a talk probably a couple of years ago on rethinking the training paradigm.

And I talked about this because in order to get stronger, you have to do more. But as you get stronger, you can’t tolerate more. You have less. So how do you manipulate that training paradigm to allow you to accumulate more, whatever to overload without accumulating too much fatigue that you degrade? And it’s this push and this pull.

So that’s when you get into asynchronous training splits where you have heavy weeks and light weeks, or maybe you’ll go into an undulating wave where you’re, where you go heavy, light repetition, or you implement some max effort and dynamic effort waves. And you can get creative with it. As long as you know what variables you’re looking at, how you’re manipulating them, and then you track progress over time.

That’s why I found Westside so fantastic or so, so fascinating was there’s so many moving pieces, you might have five or six different max effort lifts that you’re rotating in. Well, how are you going to track progress over the course of a 12 week mesocycle if you only touch a given variation twice?

Well, you have to look at, okay, what is the average load across all the variations? What is that relative percentage, right? Cause if we’re talking like max effort work, relative intensity is 10 out of 10. Let’s track average absolute intensity. So if we’re using accommodating resistance. If it’s 600 at the top, 500 at the bottom, average intensity is 550, track average intensity across.

Now we’re talking different variations, different barbells. Well, if I know my SSB is 85 percent of my low bar back squat, 85 percent of 500 is X plus or minus the chains that are on top average. And it gets really complicated really quickly, but I always found that so fascinating.

[00:52:05] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, to me, which is super fascinating about that system is how Louie got there.

Do you know what I mean? Would you agree? Well, he is autistic as fuck. I don’t think there’s any question about that. Everyone I know who’s ever met him is Oh yeah. But would you agree that I think he got there because he realized with those high end lifters for a max effort day, you, if you’re trying to push up your back squat, you can’t just go in and max effort back squat like that every week.

So then he’s got the accommodating resistance and now he’s got the rotation of your weak limit lifts. And then it’s more, okay, what’s your weak lift. Let’s work on that because we need to push volume somewhere, but we can’t push volume and intensity on the host system on the three specific lists.

Because even in that environment, you start frying people out.

[00:52:56] Paul Oneid: Yep. Well, there is survivor bias involved, right? So there are people that just completely burn out. And the people wouldn’t

[00:53:04] Dr Mike T Nelson: just train him. He’d be like, yeah, just get out of here. Just leave.

[00:53:08] Paul Oneid: And I’ve had the pleasure of training at West side a couple of times.

I met Louie a handful of times and just to give the guy like. Listen, he’s one of the coolest people I’ve ever met, not because of what he’s done or what he’s contributed, but because of who he is. So I met Louis 2013 for the first time. I met him again, 2015 after I had totaled top 10 all time at two 20 and goes, Hey, yeah, I remember you.

You just squatted 800. Congrats. Wow. That was two years ago that you met me and I was some schmuck kid. And you were met. And you remember me and you remember what I just squatted.

[00:53:50] Dr Mike T Nelson: I

[00:53:52] Paul Oneid: thought that was, you want to talk about just being a good person and making someone, someone who is nothing to you feel special.

I think that speaks to his character to a large degree. But yeah, I don’t know where we’re going from there.

[00:54:05] Dr Mike T Nelson: I’ll just give you a Louis story and you’ll think of it.

[00:54:07] Paul Oneid: Yeah.

[00:54:08] Dr Mike T Nelson: I’ve known multiple people at the start of their coaching career, like back in the day would email or call or however he got in touch with Louis.

And said, Hey, we’re going to be in the area. Can we just stop in? And he’s yeah, man, stop in. And on more than one occasion, these people in their career, literally you just started, nobody knew who they were. They got in their car from Minnesota or a couple of them were from California. Even flew down there, drove all the way down there, showed up.

And on literally almost every occasion, they just sat and talked to Louie for six hours. And Louie doesn’t know who these people are. Like, he doesn’t know anything about them. He’s he treated us like we were like the best coach on the face of the planet. And he’s we were fucking nobodies.

And we knew that he didn’t know us. But he’s just hey, do this and try this. He was just like, so into it the whole time. He’s I said, it was amazing.

[00:54:56] Paul Oneid: Yeah. And that’s, that’s exactly how he was. That, that, that was my first meeting. My, my boss, we were driving to we’re driving to the CSCCA conference.

He called up Louie in the car. Cause we had just visited Ohio state. And he’s Hey Louie, you mind if we stopped by? He’s yeah, come on by Todd. And he just showed up. And within 10 minutes I was under a bar because it’s like, Hey, get under a bar, go try this. Hey, this inverse leg curl machine, go try that.

Like, all right, let me just tear both my hamstrings in a car. But I think what we were talking about was, the rotation of max effort lifts. And this is where you have to understand that the lifters that were lifting within that system were the strongest lifters on the planet at the time. The other thing was the athletes that he trained with the same system.

He just modified it slightly. To tailor to the energy systems that they required for the sport. Plus added in a whole bunch of GPP work. Louis was also the first person to discuss assistance work as GPP to the SPP of barbell, which again, very fascinating to think of it within that paradigm where 20 percent of your work should be specific.

80 percent of your work should be general. That general work should feed the specific work. It shouldn’t just be haphazardly implemented. And when you look at it through that lens, you see how much creativity can be involved. And we’ve mentioned how complex the system is. But in reality, it’s really simple because if you do that for long enough and you manage fatigue to a point where you can recover, right?

So we’re keeping, we’re talking MRV, MEV maximal effective volume, minimal effective volume, sorry. You keep below that MRV.

[00:56:49] Dr Mike T Nelson: The maximal recoverable volume.

[00:56:51] Paul Oneid: You can train indefinitely.

[00:56:54] Dr Mike T Nelson: It’s like staying below your lactate threshold kind of.

[00:56:57] Paul Oneid: So if you just train a little bit less than your maximal.

Tolerance for volume. And you don’t need to deload because life will deload for you. You’ll go on vacations, you’ll do whatever they’ll, there’ll be birthdays and things like that. And you just chip away at these random PRS over time. And periodically you touch a barbell for some skill work. You will get stronger.

It doesn’t matter what you’re, as long as your assistance work is balanced in some way, you will get stronger. So how much complexity do we have to inject into this? This being strength training as a whole, when in reality, if you get really good at the skill, which we know can be done within 60, 80 percent of one or max periodically push that above 80 percent for some more specific singles, and then you train your assistance work like a bodybuilder aimed to maintain tissue tolerance, get some hypertrophy and get some end range joint access.

You could do that forever and yeah, like we could include some nuance of your anthropometrics dictate that you need these sorts of assistance work and your technique would require that you move in this way. On the whole, it’s really not that complicated. You just have to do it for a really long time.

[00:58:22] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, that do it for a really long period of time. Seems like that’s the part that gets lost. Now, because my whole thing the last couple of years has been what I just call violent consistency, it’s if you can just be violently consistent with whatever you’re doing, it could be even pretty stupid.

And as long as you don’t get injured, you’re going to make some progress. Now, again, I could argue, if you do it in a better way, you’ll make better progress and, put a little bit of effort into it and it’ll be worth it. But. Even in the best case scenario, like we’ve all seen the, high end athlete, the genetic freaks, and then, whatever, some of those people don’t really train that much.

And shocker, they don’t last, right? There’s the story of, the freaks of the freaks who actually train. And those are the people who are at the top for years and years on end. There’s even at the highest level, there’s no, There’s no way to avoid the work that just, you just can’t.

[00:59:18] Paul Oneid: You said something in there that I think is an interesting lens to look through. You said if they would have done it a little bit better, they would have got results a bit faster. And I always come back to, well, would they? You look at someone like

[00:59:30] Dr Mike T Nelson: Ed

[00:59:32] Paul Oneid: Cohn’s system, he lifted lightweights for lots of reps and then transitioned to heavier weights with less reps over time.

And he did that for years and years and years and years without missing lifts. And he was the strongest person on the planet, arguably still one of the greatest powerlifters of all time. Well, he is one of the greatest powerlifters. Yeah. Could you really say, Oh, if Ed did stuff differently, he would have been better.

[00:59:59] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, no. I’m just talking about the average person in the average gym, right? I would say on the high end, no matter how stupid I think their training was, and I think Ed’s training was spot on. You have to look at what were their results, right? If they were elite of the elite and they did that, what you think is the dumbest training, maybe it wasn’t so dumb.

How did they? Yeah. How did they get there?

[01:00:22] Paul Oneid: I make a joke all the time. One of my, one of my lifters, he’s 20 years old. When he came to me, he was squatting 500. He just recently squatted 705 at 22 years out of 200 pounds to a squat. He’s added. I think over, like a little under 200 pounds to his deadlift, he’s added 80 or 90 pounds to his bench press.

[01:00:46] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, that’s awesome.

[01:00:48] Paul Oneid: It’s amazing. But if you looked at his program, you would think I had mental problems. Not only that, you would think this kid had mental problems because his program looks almost the exact same as it did two years ago, as it does now, there’s been a little bit of variation here and there with his assistance work, but.

For probably 26 weeks, I think it was. So a half a year I alternated between threes and fives and I added two and a half pounds a week for 26 weeks. And then we peaked them, boom, 50 pound PR. Let’s do that again. Yeah. And we know we’ve come to learn that, okay, when we have Romanian deadlifts in his program, his deadlift blows up.

Cool. So we’re going to have some form of Romanian deadlift in his program at all times. We know that when he squats three times a week, one of those being a tempo pause squat, everything feels great and his squat progresses. We know that he can’t squat heavy two weeks in a row. So one week is a heavy pause squat.

tapering absolute intensity. The next week we’ll push absolute intensity on a competition squad. His bench press, we bench press four times a week because he needs a little bit more exposure to that. Only one of them is heavy. One of them is more technique oriented. One of them is for rate of force development.

And the other one is just to grease the groove. In that 80 percent range for doubles. So sub maximum four times a week, deadlifting or four times a week, bench pressing three times a week, squatting. And we deadlift twice a week. We do that. We tailor the assistance work to make sure that he’s moving well.

He doesn’t have to do much in terms of additional mobility work. He’s 20 years old.

[01:02:43] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh yeah.

[01:02:45] Paul Oneid: He’s also. 280 pounds with knees as big as footballs, Canadian football. So like his knee, like people who are listening, won’t see this, but his knee is like the size of, I don’t even, I don’t even know what to compare it to.

It’s huge. His joints are huge. Soccer balls. Soccer balls. Yeah. His joints are huge. So you look at him and the other thing I find funny about this kid too is he might be 280 pounds, but when you look at his technique, he lifts like a light person. So his squat stance is flat shoes.

Hip width.

[01:03:21] Dr Mike T Nelson: Really? Yeah. How tall is

[01:03:24] Paul Oneid: Six, one.

[01:03:25] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, wow.

[01:03:26] Paul Oneid: Yeah.

[01:03:26] Dr Mike T Nelson: Crazy.

[01:03:27] Paul Oneid: His hand position on the squat is pinkies on the ring. Very narrow. His deadlift stance, he deadlifts conventional with a mixed grip, but he, and even this is the funniest part. He takes his air at the bottom. Usually big guys have to breathe at the top.

So when you’re looking at him, none of his anthropometrics make sense for how he performs the lift. It’s funny.

[01:03:52] Dr Mike T Nelson: Is his deadlift stance narrow or is he like frog stance or anything weird or?

[01:03:56] Paul Oneid: No very much like just a normal conventional that I kept hip widths almost exactly the same as a squat, to be honest.

[01:04:01] Dr Mike T Nelson: Wow.

[01:04:03] Paul Oneid: Yeah. So it’s it’s just really interesting to, to see this kid for all intents and purposes is still a kid lift like a light person, be very heavy, also be able to tolerate the same frequency as a lighter person. We just have to monitor his intensity a little bit with the frequency. He’s an N of one.

I don’t have any other of my clients training the way he trains. If I tried to train the way he trains, I would die. My, my joints would melt, but I just, this whole conversation around like training and the artful application of science, I could literally talk all day about different scenarios and all the things.

He’s an expert. It really boils down to, do you know what variables you’re playing with? Are you able to manipulate those in a way that reflect the evidence that you’re collecting from that person? And then can you keep them available enough to continue to train for years and years? They will get stronger.

[01:05:06] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. It’s a, I got this phrase from a buddy of mine. He said that adaptation cannot be stopped. If you apply enough overload and I always show instead in in talks, the you’re probably seeing the overload mouse studies. Yep. Or they have the tail limb suspension, or They do synergistic ablation where they cut off, one of the muscles in the forearms or all these things where they have massive amounts of overlooks.

The mice are walking around in their front legs all the time. And then they do crazy things like castrate. They give them low protein diets and all this horrible stuff. And what they find is that There’s nothing that they’ve been able to do to these mice that will stop the hypertrophy in the front arms because they’re being overloaded all of the time.

Now, of course, if you give them more testosterone, you give them more protein, you give them more calories, will they see a greater rate of muscle accumulation? Of course they will, but it’s fascinating to me that if you have Enough stimulus, like you can do every horrible thing known to man. And we see this in lifters too, like the nutrition’s a trash bin fire.

They’re sleeping five hours a night. They’re stressed out of their mind. But if they miraculously get the stimulus, correct. They still make progress. Yep.

[01:06:18] Paul Oneid: Yeah. It’s

[01:06:19] Dr Mike T Nelson: just fascinating.

[01:06:20] Paul Oneid: It’s so frigging cool. And we talk about I’m a big believer that the lifters mind will limit them way before their body does.

Yeah. So how do you factor that into your programming and your coaching intervention? Well, it comes back to that coach athlete relationship, buy in and trust. Buddy Morris once said to us we’re listening to him talk. And then we went out we’re at the Arizona Cardinals. The Arizona Cardinals were doing like a training camp.

And one of the guys was like sucking wind. And he just yells, he’s you haven’t puked yet. And he’s The guy’s what? He’s you haven’t puked yet. Keep going. You’ll puke before you pass out and you’ll pass out before you die. You have two more, you have two more steps. And I, that’s stuck with me because.

When we talk about even the concept of MRV, most people cannot reach MRV through training alone. No. They reach MRV because their stress load outside of the gym rises. To surpass the volume that they’re performing in terms of fatigue accumulation. That’s why when you look at the Eastern block lifters who like lived in on campus and only trained in eight and had no other, that’s why they were able to make progress so much because their allostatic load was so low.

[01:07:45] Dr Mike T Nelson: No, they didn’t do anything else and that system, like you were taking care of, that was the elite thing to do. Like you didn’t really have any worries. And most of the time your life was significantly better than where you came from.

[01:07:58] Paul Oneid: Yeah. So I look at, even my own situation now, cause I just find it really easy to relate it to myself cause I’m still actively doing it.

And my workload outside the gym now compared to when I was the strongest I’ve ever been, way higher. I’m also 10 years older. So how could I expect to have the same training load and still recover when so many variables have changed? The meat vehicle that I’m driving is different. I think we need to be a little bit more conscious of how much control we have on those outside variables.

I had a really great conversation with my coach, Daniela Martina today, because I needless to say I’m getting a bit frustrated with my inability to recover. And she just straight up said, she’s you know exactly why you can’t recover.

[01:08:49] Dr Mike T Nelson: I can see her saying that. I was like, okay,

[01:08:51] Paul Oneid: yeah, for sure.

So I made a conscious choice like next week, I’m going to, I’m going to taper down my schedule. I’m going to take a bit more time for myself and I’m going to do that in an effort to show up for me. I owe it to myself. That takes a level of accountability on your part to be to have enough humility to say, yeah, I can’t do it all.

I want to do it all. Definitely can’t. So when I, whenever I hear people talk about, The extremely scientifically approach to their training and making sure they’re tapering up to MRV over the course of four weeks and then deloading and then doing all this stuff. I’m like, how the fuck do you know that you’re going to be at four weeks?

What if your car breaks down? What if your credit card gets gets compromised? What if your girlfriend, God forbid gets sick? MRV at week two, buddy. What are you going to do? That’s where the art impacts the science.

[01:09:59] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And I think that’s where it’s, and I know this applies to myself and clients, just having an honest conversation about what really are your priorities.

And I’ve made this mistake myself it was in the past I’m like, oh, you know lifting is my number one thing and then realized No, it’s not not according to my actions. It’s not even Chloe probably at some points wasn’t even in the top six I was just showing up at the gym doing shit, you know At least I feel like it’s taken me decades to at least be realistic with it, you know so for me, it’s if kiteboarding is probably my number one thing.

Like most of my lifting is actually just geared to kiteboarding. If I can go kiteboard tomorrow. Cool. Can I go ride for five, six hours and be fine? Cool. That’s number one. Number two, eh, pick up a heavy ass dumbbell. After that, eh, keep some reasonable cardiovascular shape. Body comp will depend upon what I want to do at the time period.

And the reality is those things are probably third on the list, cause you’ve got business, you have a family, you’ve got priorities, things that have to be done before that. But at least now I feel like I’m trying to be more honest with what my actual priorities are. And also being realistic I’m only really doing this for myself.

No one gives a flying hoot what I lift, what I do. I don’t really think anyone gives a shit at all. No one. It’s just something that I want to do because I like it and I find it fascinating. And yeah, I do try to open up more time so I can have, two or three days. Of lifting that I call is just uninterrupted.

If I could go for two hours, I have room in my schedule to do two hours. If like yesterday, I only had four hours of sleep. Cause I’d pick Jody up at the airport. It turns into a shit show and it’s 45 minutes. I leave the gym early, whatever. That’s life that happens, but it’s so hard because a lot of clients are like.

This is my number one thing. And I’m like, bro, you just work for yourself. You acquired another company. You just had a kid. Are you going to disown your family and just screw you all? I’m going to lift the gym for three hours. No, so you, let’s try to be a real realistic ahead of time about what this is, a priority.

You’re not a lesser human, because lifting 3rd, 4th, or 5th on your list of things to do, it, it’s okay, but if I haven’t had those conversations with people, it always ends poorly, because they’ll never achieve what they think they should be achieving in their mind. Even though they know their actions can’t line up to get the thing that they want.

So they’re already screwed for starters.

[01:12:28] Paul Oneid: Yeah, I think that was a really hard realization for myself. Even in this game for so long, a hard realization for myself the last little bit. I wasn’t even my first priority the last month. Because my wife was in prep trying to get

[01:12:41] Dr Mike T Nelson: a

[01:12:41] Paul Oneid: pro card. She was my first priority.

Then it was business. Then it was me. Well, now her and I have probably flip flopped. So it’s me, then her, then business will training is still fourth on that list. So I can’t objectively speaking, I shouldn’t be upset about the fact that my recovery isn’t great. Now, emotionally,

[01:13:14] Dr Mike T Nelson: totally different

[01:13:15] Paul Oneid: story because I do have this, and this is something that I see quite often is a lot of people’s identity is tied into training.

And I was speaking with with Keir yesterday, we did a podcast and Keir posed the question is if I asked you who you were, and you couldn’t mention your job, Or your family, what would your answer be? And most people that I coach, the first words out of their mouth would be, I’m an athlete.

I wouldn’t personally, an athlete ranks pretty low on my identity list now, but Paul at 26, that would have been the first thing out of his mouth.

[01:13:59] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah.

[01:14:00] Paul Oneid: And that plays a huge role into this whole thing that we’ve been talking about because the individual comes first, not the program. The other axiom that I like to think about is.

If I followed you around all day and you couldn’t say a word, could I know what your goals are? Simply based on your actions.

[01:14:22] Dr Mike T Nelson: I like that.

[01:14:23] Paul Oneid: That’s something I got from a friend of mine, Mark Morris. And that also stuck with me. It’s do your actions align with your goals? And could I see that just by following you around?

Most people, most of the time, the answer is no.

But if you can organize your life in a way where you’re prioritizing the things that you should be prioritizing and that you want to be prioritizing, you’re making enough time for yourself. You’re making enough time for your relationships. Who’s to say that you can’t train like an animal?

[01:14:59] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah.

[01:15:00] Paul Oneid: In fact, I think training like an animal feeds into like just Being yourself and pushing yourself and caring for yourself.

You might just have to adjust your frequency of how often you’re doing that. I was trained like probably four months ago. I was training five days a week. Now I’m training three. I don’t like training three days a week, but I also like having productive sessions.

[01:15:22] Dr Mike T Nelson: So if that means that

[01:15:24] Paul Oneid: I can only do that three times a week, well, then I’ll do that three times a week.

I’m still doing cardio every day. I’m still, my nutrition is 10 out of 10. Cool. That means I have three extra hours, two other days of the week to get other stuff done. That’s why I did five podcasts this week.

[01:15:44] Dr Mike T Nelson: Wow, that’s awesome. Thank you so much for your time. I think that goes back to everything we talked about finding what works for yourself or for the people you coach because it’s not always going to be the same.

And I know for myself, I changed the template of how I’m training probably in December because my goals changed. But even then, like the template didn’t change that much at all. Like it’s been the same basic template now for three years. Cause my goals have been about the same thing. And I found something that works.

However, if you looked at it on a day by day basis, you’d be like, you don’t follow any frigging program. Right. Because there’s a micro changes that you make on the fly of, Hey, this lift is going good, I’m going to pound some frequency out of it because it’s good. Or. Like yesterday, like half the shit didn’t go well at all.

So it just looked like I ran around my garage and tried shit and quit. And those days happen too. And, but that’s okay because you have to find some way to regulate it with the rest of your stresses. Or you’re just going to dig this massive hole that you have to recover from that. That’s not going to get you anywhere.

Couldn’t

[01:16:50] Paul Oneid: agree more,