Today, on the podcast, I’ve got Paul, the iron intern. He’s turning the tables and asking me questions about cardiovascular training, specifically how you can get better at it (make it suck less).

Episode Notes“

- Intro to Paul “the iron intern” Buono

- How do you program intensity (zones one to five?

- How do you program fasted cardio?

- How long does a session need to be for V02 max to improve?

- What do you have clients do on days they’re not doing resistance training?

- How do you manage training monotony (especially with endurance athletes who are training for an event)

- Measuring recovery and the biometric method

- Working with athletes who have autoimmune issues

- Violent consistency and the basics

- Find Paul on IG or on his website

This podcast is brought to you by the Physiologic Flexibility Certification course. In the course, I talk about the body’s homeostatic regulators and how you can train them. The benefit is enhanced recovery and greater robustness. We cover breathing techniques, CWI, sauna, HIIT, diet, and more.

Rock on!

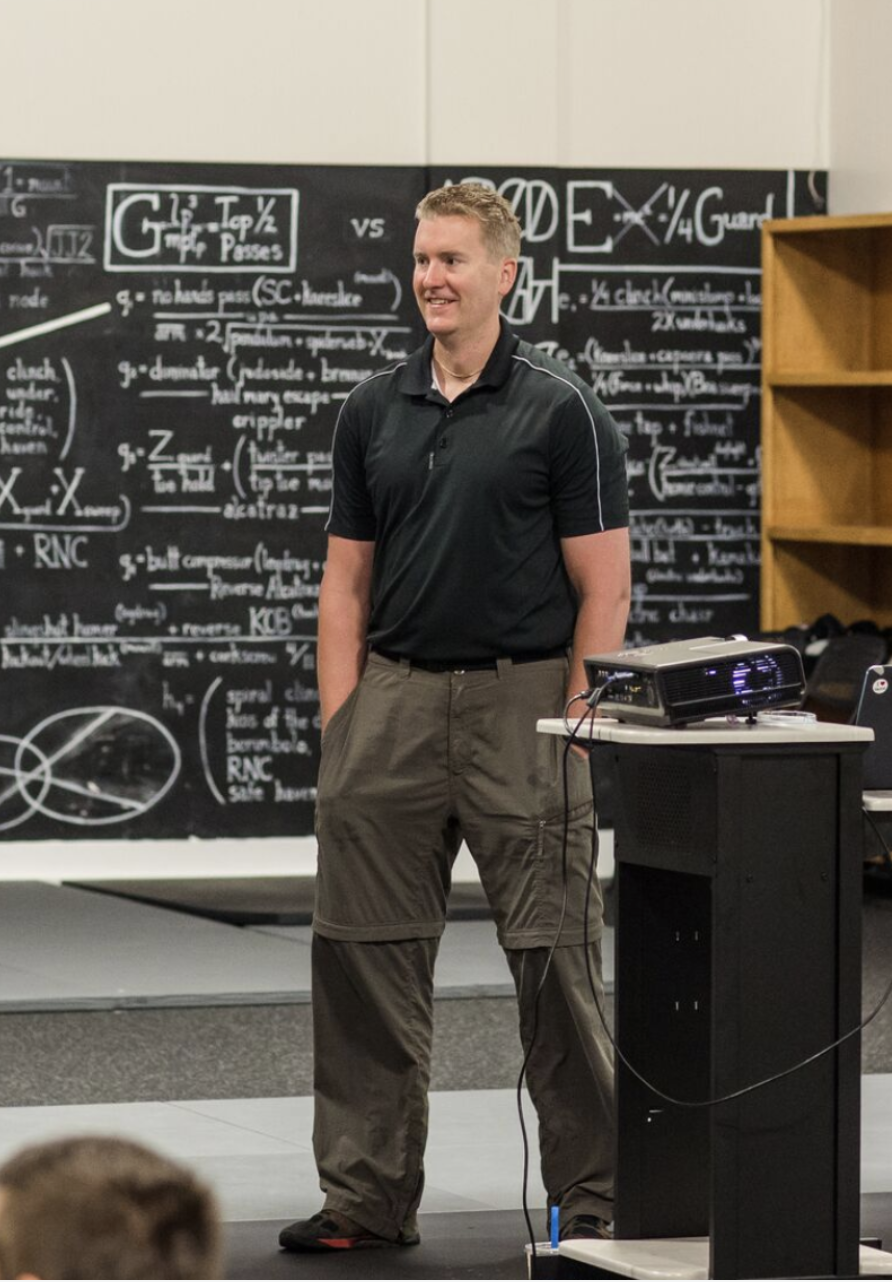

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Dr Mike T Nelson:

Welcome back to the Flex Diet Podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T Nelson. And today on the podcast, we’ve got Paul, the iron intern. Who’s gonna ask me some questions about cardiovascular training, what to do for it in order to get better at cardiovascular training. Now, before you tune out right away, right?

Thinking that, oh, I’m just a meathead. I enjoy lifting stuff, which is great. I do too. But remember that your aerobic base, which is trained via cardiovascular training is supportive of your muscle, your metabolic rate, and just literally your ability to do work in the gym. What I’ve noticed is if you have a higher aerobic vO2 max. So volume of oxygen, you can run through your system. The better you are able to do more weight training. You can reduce your rest periods and in some cases, even add more training. So if you’re listening to this and you just enjoy picking up heavy stuff, which is awesome, there is a role for aerobic training, purely for performance.

Does a course a role for it in terms of health benefits. And Paul is super awesome. Check out his website and everything. It’s great that he is doing an online internship with us here at the extreme human performance center. And he’s doing a great job and crushing it. So this podcast is brought to you by the Phys Flex certification.

This says physiologic flexibility. So how can you be more robust anti fragile? Increase your ability to recover from stressors much faster. It focuses on four main key areas which are called homeostatic regulators. The first one is temperature, cold and hot, so cold water, immersion, sauna, et cetera. Second one is pH.

This would be high intensity interval training would be one example. Body is producing a whole bunch of acid, literally hydrogen ions. We want to find ways to buffer them. This is also where the role of cardiovascular training comes in and discuss zone two training in this cert, how to set up your high intensity intervals.

Also the next, the third component of it would be your fuel systems. This would be a more expansive view than what we had in the flex diet. This is covering primarily the ketogenic end, the fat end and a little bit also on carbohydrate use. And the last one is oxygen and carbon dioxide. If you get really good at modifying all those systems, and again, this doesn’t mean you need to spend a ton of time doing them.

You can easily add this into your client’s program. Some of ’em are literally just seconds per day and they will feel better. I’m my biased opinion. You’ll have true increases in potential longevity and many other benefits. So go to physiologic, flexibility.com for all of the information and check out this podcast of the wide ranging questions, primarily related to cardiovascular training with myself and Paul, the iron intern.

Paul Bouno: When you’re setting up, zone one to zone five, how would you structure that?

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, so for people listening, like the zones are just different levels of intensity zone.

One is just barely above walking zone two, like you’re cut off, you can use the old kind. Conversation test. We used to call it the talk test, which you’ve probably heard of. You can talk and have a normal conversation. Someone listening would tell you’re exercising, but you could still put sentences together.

That’s actually fairly good for zone two type training. And if you go all the way up to zone five is like super high intensity, high percentage of what your heart rate max would be. So I go all the way back to what is their goal? What are they trying to do? And then where are they at to start?

So if we use the example you had of someone trying to improve their two K, are they near the bottom of population status or are they up near the top? And I still use the calculator. So for concept two, you can go into their site and you can go per age and heavyweight or lightweight, male, female, et cetera.

And so for their demographics, I can go in and look and be like, okay so I had a new client start literally just the other day. So he’s at, he’s like the bottom 10% of where he would be. And granted he hasn’t done any rowing and by his own admission, hasn’t really been training much as of late has trained a fair amount in the past.

So he does have a history of doing it. But when we had him do his two K tests, which granted he hasn’t done a lot of rowing just picked up a rower. It’s probably not gonna be the greatest, but it’s gonna be a pretty good ballpark. So he is in the bottom 10%. So for someone like him, almost any cardiovascular training he’s gonna do is probably gonna be a benefit.

So for that, if I had unlimited time and he had unlimited time, I would probably do more of an aerobic base, like zone two type program. So for people listening zone two, then you’re. Looking at literature goes back and forth. But I would say a minimum of probably two to three hours of very light intensity of work per week.

So if you’re doing it three days a week, that would be an hour. If you’re doing six days a week, it’s about a half hour and I’d normally run that for four to eight weeks, which is pretty boring. No one really likes it. It’s not necessarily hard, but it’s very time consuming. So your goal with that is you’re just trying to get a low level of aerobic performance or what they classically call aerobic base.

After that, then you can get into something a little bit more specific. So the third issue is that you’re also taking what would be an ideal situation and you have to make it realistic for the client. So in engineering terms, I always think of what are the constraints on the system? You may get some athletes who are like, yeah, whatever you need.

That’s cool. I’ll make time for. Eh, it’s not most people they’re like, I only have 45 minutes, Monday through Friday. So now you’ve gotta take, what is your ideal situation? And then boil it down into, what’s gonna get them to make progress within their own constraints.

So for him, we just did a mix of what I call unloaded rowing. So again, if we’re using the concept to rower, you can take the damper and just put it all the way down. So your resistance with each pole is gonna be really light. And the reason I did that is I want something that’s more zone two-ish.

That’s a little bit easier. Now, granted, if you’re gonna try to get a max two K row, you probably don’t want to do that because your frequency of how fast you pull it has to be really high. So the damper is just the resistance of how hard you have to pull it. It was designed as what’s called a drag factor.

So the concept two erg is trying to replicate, on the water rowing. So when you’re on the water, you’re in a rower, it has some drag factor of it moving through the water. So on the concept, two rower, you can adjust that factor by moving the damper and go to something called drag factor and see exactly where it’s at.

So for him, I did something called it, unloaded rowing, which I think I probably stole from dark horse rowing and just relabeled it. So it’s super easy. And then just accumulate time there we’ll do maybe some, two K ish practice or work up to that. And then we’ll do one 500 meter. So for him, I’m trying to get a little bit variety of the longer stuff.

I’m purposely making a little bit easier, some moderate intensity stuff. And then I still want a little bit of high intensity, but he’s only gonna do one 500 meter. Part of that is also. Me guessing that personality, because a lot of people, if you just said, oh, go do a two K every day.

They’re like, oh, screw you. I’m not doing any of this. So you have your constraints on your system and then you have compliance of what you think, even within the time limits they have, what they would actually do. So you got their starting point. Are they at the bottom or kind of the top percentage?

What are their constraints on the system from time? And then what is the adaptation I’m trying to get and what is compliance? And in terms of adaptation, the lower they are, the more you can do almost anything, right? It’s just like lifting, Betty’s never lifted a weight in her life. She could probably curl frigging soup cans and get stronger.

It doesn’t matter. You don’t need to get super fancy, but as you scale. I’ve got another client who’s at for a two K percentage wise, probably about 65% of the population. And so when you look at the concept two site, these are people who are nutty enough to actually take a phone and track their performance on a rower.

So they’re definitely not general population. So even a 50% in that population, because they’re already specialized in rowing. know, That’s a pretty good standard, most people, if I can get their two K to, 50%, you’re gonna see a lot of positive transfer with that. You go from 50% to 75% of the population there.

Yeah. I think you’ll still see some transfer. I think it’s good, but you’re probably gonna need a lot more specialized work at that point. So I have another client. Her goal is to do a 5k in 21 minutes. So that would put her at a pretty high percentage of the population for where she’s at. And so that’s something we’ve been working on for, several months and she’s done really good, made some good progress with that.

But as you scale up and get more and more specific and you get to a higher percentage, then you a hundred percent have to be more specific with the adaptation that you want. So she already has a pretty good aerobic base. She can roll 5k and do fine, and she can come back the next day and be okay. So for her, a lot of it was adding a little bit more frequency.

So we added some six minute rows in the morning just for her to get more exposure because she’s at a higher level, she’s gonna need a little bit more frequency, she also has a life also has a job, so she can’t just spend all her free time rowing either. So in those people, I like to have more frequency.

Real simple one is just have people work up to Monday through Friday, just six minutes of rowing, like an eight RPE of an eight. So an RPE rating of perceived exertion, an eight is hard, but doable, like even a seven or an eight. But it’s something you can probably come back and do the next day again.

And then for her, we are having to do a lot of pace work. So if you think back to, what is a specific adaptation we want to. It’s a certain pace or certain time. So her goal is to, know, row 5,000 meters within a time 21 minutes. So we know for her to hit that, what pace she would have to be at, and we’ll have her do some pace work with usually like a complete rest.

And then see if you can repeat that again. You could even go, if they’re missing the higher intensity end, you can even shorten that. So one of the things I’ll do is 30 or 60 seconds on like pretty hard and then rest for quite a bit and then go again. So that would be like a higher intensity day.

Or if you look at max strength, you’re just trying to increase your overall max strength and then she’ll do some pace work, right? So six to eight minutes at what her ideal pace is. So the takeaway from all that is that you have where they’re starting, are they lower high, right? Or even in the middle.

If they’re low, eh, just get ’em to do some stuff with halfway decent technique. They’re gonna do better as you start escalating up. I like having more frequency and then you have to get more hyper specific with what is the adaptation you want. So if they’re really low on just hard speed and power, so the 32nd wind gate is low.

You might wanna push ’em a little bit more towards that end. You’re definitely, probably gonna need some specific pace work, where they’re doing the thing that they want, but in her case, for several minutes, but definitely not the 21 minutes at that point, and then have an accurate point of where they’re starting.

So I like using just the two K get on the rower, set it for 2000 meters, see how fast you can do that. And you’ve got lots of population status. You could translate that to a VO2 max, and so volume of oxygen, the aerobic level, you can look at that from population standpoint. And then from there you’re just programming within what you think they would do within the time constraints they have.

And then also stuff like equipment. A lot of clients, I have, they have a rower at their house. So if we use that or a bike, they get up in the morning, they can easily do six months in the morning. It’s not a big deal. For a while, like when I didn’t have one at my house, I had to go to the gym in order to do it.

It honestly, almost literally, almost never happened. The thought of me getting up earlier to get to the gym, to just to do cardiovascular stuff, and then to come back later to weight train, even if I trained in my gym here just didn’t happen. So in those cases, again, you’re back to compliance. You may have to start mixing a little bit more modalities, strength, training, and whatever aerobic stuff in the same session.

That’s a lot of stuff. I know

Paul Bouno: Yeah no it’s really helpful. I just have a lot of little questions to bounce off of that. And I don’t know if this is something that you want to talk about cause it is in your course, but like you talk a lot about in your course training fasted with on your cardio days.

Yeah. So on a, on an effort of an R P E eight for six minutes of a rowing, it sounds like that could get pretty anaerobic and you would probably use some type of carbohydrates as a fuel source. So for just six minutes, does that really matter? Are you having clients and athletes, maybe take a little Vitargo or some type of Carbs beforehand or are they typically doing that fasted?

Just because it’s six minutes and it’s at an R P eight R P E eight for six minutes. It’s relatively recoverable.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. I don’t worry about it. Because the six minutes, I’m just thinking about. How can I add something that’s high quality, but add more volume within the constraints of where they’re letting me operate.

And I also found that most people, if they get it done in the morning, there’s less reasons for it to be interrupted later. It’s short enough. Like I’ve had some people start out with your goal is to get up in the morning and just sit on the rower for 30 seconds. I don’t even care what you do.

And once you got 30 seconds, then do a minute. And then do two minutes. So your goal is just to, to show up number one. And then we can look at their times. For some people I may have, ’em start with, eh, just nasal breathe. So their RPE probably gonna be six or seven, even though their output’s gonna be a little bit lower.

And then over time we can scale up the intensity a little bit. But even if they’re doing RP of an eight for six minutes, ah, I don’t really have, ’em worry about it. Cause when I’m really trying to do is I’m trying to increase the floor of what they’re doing. So a lot of people talk about, oh my 1 RM is this, my max is that I’m like, that’s cool.

And that’s great. And we definitely want to move those numbers up, but then I’m also interested in what is of the floor. What is something you could just walk in that. Half, hung over because you went and partied all night before slept four hours and you could still execute from both a lifting and a cardiovascular standpoint.

And that’s the number that I wanna see go up over time from just more semi daily exposure. So for me, for right where I’m at now. Yeah six minute row, I can hit 1500 meters pretty much every day, unless something really dramatic happens RPE generally around an eight sometimes is a seven, sometimes a six and rare occasions.

If I went to a concert till two in the morning, eh, it might be a nine, but it’s something I can still do without absolutely torching myself in the process. And I’ve noticed that as that baseline, that threshold goes up, in good days, I’ll hit, 1550, yesterday. I hit 15, 20, nasal breathing the whole time.

So there’s variability in it, but I think having some minimum quality you want to hit. We’ll go quite a long ways to do that. If you put a metabolic card on it, like the numbers in terms of what fuel you use are like all across the map. So I’ve got a couple clients that we’ve done this with. I’ve done it here and it’s variable like day to day, and I don’t know if that’s, I’ve tried to correlate it to like heart rate variability and stress levels might just be pure intensity. Some days you feel better, it’s easier. Some days it’s harder. So that’s probably gonna change a little bit. But in general, that’s a secondary benefit, I think that easier you make it is good.

And from a fuel percentage standpoint, You’re probably gonna have enough fat. You’re gonna be fine. Liver glycogen is gonna be a little bit lower, but you’re gonna have, plenty of muscle glycogen, unless you just did something really stupid the day before and didn’t eat. So even if you’re using a little bit of carbohydrates, you’re gonna have more than enough fuel on board for it.

And I don’t worry about it because I realized the more I complicated that in the morning, like the more people just didn’t do it. So even something like I tried and this works for some people, but I said, okay, if you have six minutes, total time, I want you to do some higher intensity stuff for three minutes, like a 32nd on 32nd off, which is pretty brutal.

But take three minutes to warm up. And even that was a little bit harder because the mental thing of oh, now I gotta get on there. Now I gotta do a warm up and now I gotta rest. And now it’s higher intensity. And I found just. I don’t even have people do a warmup, just get on there, do some RPR or something beforehand for a few minutes.

And then just start don’t even worry about a warmup. Like it’s specifically done while you’re cold, which of course is gonna be sub max. But again, that’s the whole point, right? So how many barriers can I remove beforehand to make it as simple as possible so that the consistency is there?

Paul Bouno: Yeah. I really like that. I like the the fact that there’s no warm up. Cause I know even for me, there’s certain days where I’m like, ah, I don’t mind training. I would love to train, but the 10 to 15 minutes I have to take to get ready to train is just a little bit too much for me today. So I really like that.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And most people feel like it’s never anything even now. Like I don’t really look forward to it, but I just feel like my even six minutes, like my brain feels better after I feel a little bit more organized. You’re a little. A little bit more awake and you can expand from there. There’s nothing super magical about six minutes, there’s an old study.

God I’m blanking on who the hell it was. Now. It was like from the 1970s that showed four to six minutes of relatively high output stuff, could increase VO two max granted they did it as repeats in that study. And I’ve just noticed that people do better with that. And it’s variable. Like I said, some clients are only doing 500 meters.

Some clients are doing two K’s, a few nut balls are doing like five K’s every morning at an RP of a seven, so it’s variable depend upon your goals, your time and what you’re trying to do.

Paul Bouno: Yeah, I think it’s interesting cuz you said the four to six window increases VO2 max.

Very well. In multiple sets I feel like I’ve come across a couple studies and and more coming out around frequency training. I know a lot for strength training has come out, but when I hear like the six minutes every day, I’m almost interested in is that just a very long interval?

Like with 23 hours and 54 minutes of rest in between. So it’s, I think that’s really interesting too, because I think that could probably have some good benefits.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. I just found like for, if you go down the molecular pathway for how long, certain things stay active for molecular standpoint, with aerobic training, not necessarily high intensity training, it’s debatable, but if you force me to put numbers on.

Four to six hours maybe less. It appears to be shorter. If we compare weight training, we look at MPS. So muscle protein, synthetic response. If you’re a highly trained person, maybe that’ll stay elevated for 24 hours. If you’re not 48 to maybe 72 in semi trained people. So you’re talking, day, two days, two and a half days, you’re talking, quite a length of time, you could argue that, intermediate people, eh, trained every other day, that seems to, make sense with that.

And the molecular underpins, don’t always map out to what we find in, longitudinal studies when we do that. But it is some pretty good indication. Real big stuff tends to be shorter unless you get into super long, event training or high intensity work. So my bias is that do in the morning and then yeah.

Do some weight training in the afternoon. Much less interference effect. Again, 99% of people listening to this, don’t have to worry about an interference effect really at all. But from a standpoint of you’re dealing with a client who may not be the best aerobically conditioned, I don’t really wanna beat ’em up with a bunch of aerobic training and then expect them to go lift right after.

I don’t think it’s so much an interference effect. It’s just that now I’ve decreased the quality of their weight training session and yes, they could do some aerobic training after lifting too, but you’re back to compliance and quality and that kind of stuff too. So the perfect world, I like having them split, let the molecular adaptations run their course and then hit it with whatever the next thing.

Paul Bouno: Okay. So what about on the days that they’re not doing resistance training? They’re still doing that six minute row in the morning. Will you have them do some of the zone two base work or anything more intense depending on the goal? Like maybe it’s not a two K it’s 5k or someone that’s trying to do a little bit more of a hybrid training where they even doing longer events, maybe a marathon’s the goal.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. So longer events. My general template that I’ve used God for shit 12, 13 years now was just Monday, Wednesday, Friday, go pick something up, lift, heavy, moderate body building, whatever you wanna check, just do some, more performance based weight training Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday.

Do some type of aerobic stuff, and that’s gonna vary, depend upon what the person is doing. So my good buddy, Dr. Tommy woods, we’re getting him ready next year for his third strong man event. And his aerobic base is pretty good strong dude. He just does 20 to 30 minutes of aerobic stuff.

Tuesday, Thursday, maybe Saturday, if we’re doing a medley or not doing anything, conditioning specific, and he can held his aerobic base super easy, four weeks out from a strong man event, we’ll have some more 60-second repeat stuff. And his conditioning for all the events. So far, the two he is done have been, right on point.

Granted, he doesn’t need to really develop those systems a lot more. We may do some intervals. We may do some other heinous stuff once in a while just to bump him up a little bit in the off season. Cause from my bias with something like strong man, Conditioning is probably the easiest thing that you can control that most people have programmed intelligent will respond really well to.

And that’s many months, but getting just stupid strong is many years to decades. so control the things you can control, which to me, for people that I have compete, at least in strong men, like conditioning, shouldn’t be one of their limitations. If you just didn’t have the max strength to lift it because the loads are stupid heavy, then yeah.

There’s only so much you can do about that. There’s only so much we can accelerate that process. You start getting into longer events than. You’re back to, what is your main goal? So is your goal to run a marathon. Cool. Then we may invert everything. So your main running might be more four days a week.

Your lifting might be two or three and lifting, may only be two, depending upon what you’re doing. So with that, you’re looking at what is their VO two max, if their VO two max, these population standard is not at a bare minimum, average to better than average then. Yeah. I’m probably gonna do a lot of zone, two training, the caveat with running.

What I’ve noticed is that depending on their technique and what level they’re at. They may not even be able to do zone two running even now, if I try to run really smooth, really slow, and I’m not a runner at all, I’m way in excessive zone two, like even now after trying to do it for three, four years.

And it’s just because I’m not that efficient at running. My mechanics are not horrible, but they’re probably not the best either. And I don’t do a lot of running for someone else who is a high level elite runner. Yeah. They could probably do some zone, two stuff for that, but I’ve just noticed with athletes, you have to stick a heart rate monitor on ’em and see where they’re at.

Even when you get ’em to just do nasal only breathing and just run really slow. I tell ’em, it should be like super quiet, super smooth. Some of ’em can’t even get their heart rate low enough to hit zone two. So for that, a lot of times I’ll use a bike. But once they’re past that. Then you’re looking at the handful of people I’ve framed for marathons.

It’s most endurance athletes are just in the same zone every single day. What do you do? Oh, I rent and ran seven miles. Oh, I rent and ran eight miles. Cool. That’s awesome. But at some point when you can do say eight miles repeatedly, we have to talk about what is your pace, and that comes back to what is your goal?

Some people it’s Hey, my goal is just to finish a marathon. Cool. So what is the time that they kick you off the course that you have to beat? we probably wanna be a little bit ahead of that. Some people are like I wanna beat Oprah’s time in the marathon. I was like a big thing a while ago, or, I wanna get sub three or whatever it is.

So once you know what that goal is, then you can back up and go, okay. Can you run one mile at that pace, right? Can you literally run half a mile at your race pace and just start to build them up from there? So for the running stuff, then I’m either looking at real simply, is it pace work or is it like just super low, moderate recovery zone, twoish type work?

In pace work, you’re looking at some form of interval for most people and that’ll work pretty darn good. And then I’m looking at building volume at whatever pace it is. So if it’s a three hour marathon pace, cool. Can you do one mile at that? Great couple months later, can you do three miles at that pace?

Awesome. So I’m just looking at month over month, week to week escalating how long they can go at that pace. And again, same thing, like bringing up what is their floor of performance? Okay. So if you’re half hungover today, you slept four hours and you went and did a four mile run. What is a pace, you can absolutely hit.

And if that number’s going up cool, like your best is obviously gonna be, higher than that. So again, it’s back to, what are you trying to do? What are the priorities? Also for endurance people, the literature is real mixed. Like you may get by only one or two days of lifting probably more lower body ish focus type stuff, and just looking at range of motion of where they’re weak, and then you can get more specific.

And then the last part too, that people tend to forget about is just running economy. If you’re gonna go run a marathon like itsy bitsy, tiny increases in your running economy. Extrapolated out over 26 plus miles, that makes a massive difference. And I think a lot of people just do too many sort of junk miles where they’re like, yeah, I did 10 miles today.

And you watch ’em after mile seven. And it looks like, like one of the zombies like chasing you from a bad movie or something, it’s yeah, you made it. But this isn’t the race day. This isn’t the day to pull out all the stops and just cross the line no matter what, like you probably should have stopped around mile seven, right?

Cuz your form just degraded so bad that your efficiency is not good. Your rate of injury is occurring and you’re just training the wrong thing. So that’s a big thing again, I use a lot of RPR reflexive performance reset for that last tip on that too is again, I don’t do this with a lot of people, but some people visit here.

Actually, if they’re doing endurance stuff, I actually just train them like sprinters. And again, I’m not a very good sprint coach by any stretch of the imagination at all, but just basic stuff. Hey, do you notice your left arm is almost gonna hit your right eye, out because you’re crossing the midline so hard.

That means something’s wrong. It’s the one thing I got from Chris Corpus and Cal Dietz Cal was saying that even with his elite athletes, like he doesn’t teach running mechanics at all anymore. Even with, athletes have more straight ahead sports. He’s that’s a diagnostic to tell me what’s going on in their body.

And you’re probably not gonna be entirely able to cue them out of it. But if I see something that’s not efficient, then I know I need to change their training. Do some activation work, do something else and then have them run again and see if I fix their problem, which I think is same thing I run into.

If you tell someone, try to consciously change this thing, when you’re running. I think you’re actually promoting a risk of injury and when they get tired, they’re just gonna forget it anyway. So you want all that stuff to be hardwired subconscious. If your right arm is coming all the way across your body like this, I can guarantee there’s something that’s not going on with your left leg.

I, I would bet a lot of money. You’re losing stability in the frontal plane or your left leg is not cycling into extension. So the takeaway there is just small mechanics changes in running make a huge difference over time.

Paul Bouno: Yeah, no that’s really helpful. Especially thinking about as the sport lengthens out, but that brings me to the next question is like training monotony and load spikes.

So one of the things that I’ve been doing for a long time with my athletes is just like a simple way to calculate session load of multiplying session RPE by the duration of time. And I like that because. It gives me a good sense of what’s happening on their resistance training days and their energy systems, cardio cardiovascular training days is a perfect, no, but at least I get a picture of what’s going on throughout the week for someone that has a goal of an endurance sport, let’s call it a marathon.

Let’s just call it a marathon tur piece. So they wanna run a marathon. So their cardiovascular training typically is a little bit higher than their session though, would be higher than just a general population. What would you do with their, that person’s the marathon athletes resistance training to manage the training monotony throughout the week.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. So by virtue of you wanting to run a marathon, you’re going to have training monotony, right? That’s just there’s no way around that, if you, yeah. Could train for 10 miles and complete a marathon? I’m sure you could. I’m sure there’s people who could get up right now and complete a marathon, but if you wanna do it and be able to walk the next day and have some semblance of not massive injury risk and everything else, and just can add fortitude your way through it.

You’re probably gonna wanna train up to, 20, 22 miles, something like that. And it’s debatable, but probably don’t need to go all the way to the 26. All the classic stuff says 20, 22 miles, but you’re gonna have to put in, there’s no way around that. You’re probably gonna have to put in a fair amount of mileage, right?

If you are experienced running marathons, could you get by doing a lot less mileage and just doing some high intensity stuff? I think you probably could, but if you haven’t really done it before, you just have to accumulate volume, at some point, like if you wanna be stronger, You have to accumulate volume somehow, right?

There’s just no way around that for strength. So I would say the strength training can serve as a way to break up some of the monotony with that. Then you’re just looking at what positions are they weak in? Most of running is gonna be split stance, which doesn’t mean you should never squat or do anything like that.

But making it a little bit more specific to their sport, I think is good. So Cal Dietz has like a split squat that he does with basically like a hybrid lunge using a safety squat bar. Lots of lunging forward, backwards, squatting foot ankle stuff. Chris Corfu has some really good stuff on that.

So you can use that, I think to break it up, but also just depends on how weak they are. If they’re someone who has a background in lifting. You may not have to do much lifting at all. They may be more than enough strong for running. You just might wanna make a little bit more specific. So I’ll use that to break it up.

Usually lifting maybe Monday, Wednesday, or Thursday, and then they’re doing more aerobic stuff the other days. And in terms of, I agree with intensity, it’s super hard to measure, right? There’s all these systems out there that look at, how much, zone five did you do versus zone two and your training and you’re recovery..

And we can take RPE and multiply it by volume. And then other people are like, no, your warm up sets don’t count. And other people are like, no, it’s only the hard sets you did. And how many, how many reps away are you from failure for lifting? And I don’t, I think all of them can be useful and there’s a time and a place where you want to have some idea of what you’re doing, but I don’t know what I’ve done is I’ve just.

And one thing I really look out for is like a load spike, which is Tim GA’s research, which says that if you went from a low load to a high load, like very short, your risk of injury is gonna be much higher. Doesn’t mean you’re gonna get injured, just means your risk is higher. And with most people who are already have the habit of training, the only time you really run into that, unless you’re an idiot programming is if they just completely F off all week and do nothing, and then you don’t alter their next program, that’s usually where you’ll run into issues or they go on vacation or something happened at work.

And now they can’t do six days of training. So they did literally nothing. And then next week is like a moderately high volume week and they go, oh, I’m not gonna tell my trainer. It’s gonna be fine. Eh, you might skate by, it doesn’t guarantee you’re gonna get injured, but your risk of injury is a lot higher.

So I do try to look out for those things and then. The rest of it, honestly, I just guess and go, what have I done in the past? But I monitor what I call the cost of doing the exercise. So first time I look at their output what is their performance? If you measure nothing else at all, and their performance is trending down and you did not do that on purpose, like you did not program a one or two weeks overreaching where you’re expecting their performance to drop, then something’s wrong.

Like something’s going on. It may not be your training might be the recovery. It might be, they’ve had a death in the family or their dog passed away or who knows, a minute. I Anything related to them physically. But if you’ve got that all taken care of, I just look at heart rate variability in the morning.

So it’s gonna give you a status of what is their autonomic nervous system parasympathetic to sympathetic. So it’s gonna tell me the overall stress that’s on their system right now. So what is their physiologic response to all the inputs coming in the body is saying like the tachometer on your car.

Oh, boy, we’re getting close to the red line here. We’re you know, watch out. The other one I’ll use is also resting heart rate. Resting heart rate is a very crude proxy of a aerobic performance. So over time, if you’re doing a lot aerobic training, you should expect your resting heart rate to slowly be going down over time.

Again, it’ll fluctuate day to day. The last one is I do use a two minute heart rate recovery test after doing some higher intensity stuff. They’ll stop like a, I have a garment will do it automatically. But have to make sure you’re on the electronic heart rate strap. The optical ones for high heart rates are just dog shit.

Right now they’re getting better, but they’re still not very good. And all it’s doing is looking at Maxar rate. How far did your heart rate go down in two minutes? So stand there. Just breathe. Don’t move around, do whatever you want. And that’s a pretty good marker of what’s called parasympathetic reactivation.

So if that’s recovering quite well. That means that your system can handle the stress and literally get back to baseline faster. If we see that your HRV is trending high, right? So you’re trending more parasympathetic, eh, you’re probably doing okay. HR V is dropping. You’re trending more sympathetic, more stressed.

Then I’m gonna look at, how’s your heart rate recovery been? Oh, your heart rate recovery. And your last three runs has been absolute dog shit. Okay. So now we know that something’s going on. And even if your performance you’re able to hold that level of performance, I know that you’re doing it at two high of a cost.

And again, if you’re measuring RPE, you’d normally see RPE would go up, right? Cause some higher level people are like, Hey, I’m gonna hit this pace. No matter. And they’re not always the best about reporting their own RP and they tend to lie. Not intentionally. They just like doing, CrossFit’s a great example of this, you see someone laying on the floor for 20 minutes bro, what was your RP on that?

He’s ah, that was like a six, it’s like, you haven’t moved for 20 minutes. I think it’s higher than a six, so I like more physiologic measurements to get an idea of where they’re at. And then yeah, I do use RP and other stuff too, but it’s more of a surrogate marker. Yeah,

Paul Bouno: cool.

I guess like what I’ve I, what I’ve pulled from all that, and what’s really helpful is it doesn’t sound like there’s too much worry day to day of Hey, Monday is a high volume, high load day. We’ll just call it out low day. So Tuesday needs to be low load. It looks like you’re looking at it at, in a more chronic versus acute.

Like you’re looking at the big picture. Okay they might be training pretty hard throughout the week, but at the end of the week, let’s see, how are they recovering between sessions? Are they able to handle that? And then making adjustments along the way to of find their optimal place with the recoverability, whether you’re gauging it off RPE or HIV or even heart rate.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, I’m just looking for trends, cause everyone has an off day, eh, one measurement, it drops a little bit. Ah, don’t worry about it. The other part too is keep in mind that if I’m really hammering someone like I’ll again, I still this from Cal too, like the more higher level, higher intensity stuff I tend to put more earlier in the week.

Okay. So Sunday for most people is gonna be an off day. So Monday or Tuesday is gonna be the more intense stuff. Not always, it just depends on how it’s programmed. But if Monday is like a super hard I got this from Kenneth J if you can do 30 seconds all out at a high percentage of your VO, two max, like above 150%, maybe an 170% with 30 seconds rest.

And you can do that for 10 rounds. That’s badass, right? That is extremely difficult to hold that output with compressed one to one work, to rest ratios. So if I’m doing something like 30 seconds on, even with an open-ended rest period, and I’m having you do four or five or six rounds, or some of these other heinous rowing programs, and you were lifting that day, I’m actually expecting your HRV to probably be crappy the next day.

If it’s not, I’m probably gonna up the intensity again. So on some days I actually want some erosion of where you were at, right? Because that tells me that I stress the system significantly enough. But then again, I will, Tuesday’s gonna be a light day if we did that. And then by Wednesday, I’d wanna see you back to normal because it’s gonna be a moderate day again, so it’s not always, so some people get caught up in like a heart rate, variability. They’re like, oh, you gotta be like increasing your parasympathetic tone the whole time. And. I’m like, no, if someone especially is a strength port athlete, like they’re trained for strong men and their HR V is already really good.

And it keeps going up like either they’re gonna be parasympathetically overtrained or overreached, which is unlikely, or I just didn’t give ’em enough volume. Like I need to beat ’em up more right. Cuz their body is saying, Hey, this wasn’t enough. So again, it’s, you’re back to the context of everything.

In marathon people you can see the opposite, they can actually become parasympathetically overreached. So if you’re doing a piss ton of zone two training and you’re just hammering them with the super long distances, you can see parasympathetic tone, just going up and up and get too high. So they can be what’s called parasympathetically overreached.

And those people have a hard time getting their heart rate high enough. So if we programmed an interval day, like the 30 seconds on the rower, their max heart, rate’s 180 7 and they top out at 1 55. Ooh, something’s wrong there. But most people, if they just looked at their HR V would be like, oh, their HRV is amazing.

So they have to be great. No, it’s been too high for six weeks. That something’s wrong. You wanna see if you hit ’em with like higher intensity stuff, it should drop a little bit, or they should at least be able to hit like close to their max heart rate.

Paul Bouno: Yeah. So with that when you are having someone work into a tough interval, I know we’ve talked before about using the biometric method and watching their heart rate and letting it drop below a certain beats per minute, somewhere between a hundred and 110.

So let’s say you have someone work up to, the 150 to a hundred, 170% of a 30, 30 second sprint. And you want him to rest for full recovery? The second that you see 110 beats per minute on their little Garmin watch. Are they going again or are they seeing one 10 and then it’s rest another 30 seconds or rest another 60 seconds?

Like how long do you wanna see them under that heart rate range before you’re having them go for their next effort?

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. So again, biometric method. I probably still list again from Cal Dietz and it’s the same idea of like velocity based training. There’s always other training modalities and I needed something for was primary on a training CrossFit people like they just would, everything was circuit training.

And then unfortunately, female lifters tend to do this too. Like the program, I’m like, how’d you finish that in 20 minutes? I just didn’t rest anymore between any of it. I’m like, this is string training. This is not like circuit training or a met con, but everything turned into a Metcon.

And so I was like, just pulling my hair out. And so I said, all right, here’s your deal? Do whatever exercise and you can’t do the next one until your heart rate hits, say a one 10. So I give ’em a heart rate range. So now I’m forcing them to bring their heart rate down and to go again. And I saw this on the rower because it’s very easy to measure output.

You’d see I’d program, like 30-second intervals. Okay. It’d say rest completely. And then do the next one. And you’d look at their total time and you’d look at their power output. And just went off a cliff, like interval four was like half the power of interval one. And I’m like, what are you doing?

bro, that was so hard. I’m like, yeah, it’s gonna be hard. But your fourth interval is a distress where you’re literally at half the output of the first. So I said, okay, let’s have a heart rate spec. So your heart rate, do 30 seconds on heart rate hits, whatever it hits. Let’s say you’re warmed up, hits one 60.

You’ll go again, based on heart rate. So if it’s a, advanced person that may be 110, 120, I was with Cal this past weekend, like some of his advanced athletes doing some of his stuff, shit. Their heart rates are seized, are still like 1 35, 1 40 or higher. But they can go through and just do all these exercises with like violent execution, but they also have a super high aerobic base and they’re younger college athletes and this is, what they do, so again, it’s gonna vary, depend upon your population, but for most people I would expect, know, anywhere it’s from 85 to 110, 120, somewhere around there. If I’m really prioritizing the speed and power aspect, I’m gonna actually want them to recover more. If I’m pushing a little bit more, quote, unquote conditioning, the rest, period’s gonna be a little bit higher.

If it’s an all out, just complete distress session where I’m purposely compressing rest periods, like the 30, 30 protocol, then that’s something that’s gonna be very advanced. And at some point on that, I won’t measure heart rate. It’s just can you hold your output and get through it? But for most people, a hundred hundred and 10, so you’re watching your watch 1 50, 1 45, 1 12 1 11 1 10.

Great. Go again. And then, okay, you do your 30 seconds, same thing. And what you’ll find is like your heart rate needs longer time to recover when you do more work, because you’ve got more fatigue. So the part that I’d never understood for years was like on lifting stuff. Everyone’s okay, do set one 32nd.

Reary do set two 30 secondary do set four 32nd. I’m like, wait a minute. Okay. If you’re doing a specific density based program or a Metcon or something on purpose, I get it. But if you’re prioritizing performance, you’re telling me you’re only gonna need 30 seconds to rest from set four to five, but you need 30 seconds from set one to two.

Like even if you’re trained in condition, that makes no sense whatsoever. Your first couple ones, you’re probably not gonna need hardly any rest. And then later you’re gonna need more rest just cuz you have accumulated fatigue. And when you don’t do that, you’ll see output just drop off in most people.

Again, if you’ve got a highly developed aerobic system, you can compress all of that. So it as a workaround to give people a goal and give people then an incentive. So now I just gave them a massive external cue to figure out how to get their breathing under control and figure out how to get their heart rate down faster so that they can go again and it gives them a direct marker.

And I don’t have to guess at, there are times. Cause the hardest part I had with online programming was like, I don’t know, I’m not watching you. I don’t know if 30 seconds is enough time, 60 seconds, five minutes. On some of my, I’d say more performance, upper body stuff. Like last week I rested five minutes between one set and the next set and I was set between set four and set five.

Cause I didn’t want any rep drop off at all. I only had one rep that dropped off, so again, depends on what are your goal? What are you trying to prioritize? And I guess people just parameters to do that. Yeah. That’s

Paul Bouno: I think that’s really helpful. So just letting them you’re setting the heart rate that you wanted to get to based on the response you want from the workout.

Yep. Yep. And then maybe once they get there, it’s like, all right, you got there. You’re ready to go. Hit it again and just keep going through it.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And if you wanna get crazy, just measure the total time, right? So let’s say four rounds at 30 seconds on the rower. You go again, when your heart rate hits one 10 go the first week that’s hypothetically, it takes you 12 minutes, 37 seconds.

Great. So I give you the exact same parameters, but over time, like after six weeks now that exact same thing, but the same quality, the same output, the same repeat you can do in nine minutes and 37 seconds. That’s a huge progress. And so you don’t have to. What I liked about that is I don’t have to change the parameters almost every week, either.

There’s a built in overload mechanism and I can just look at the total time, as long as you’re hitting the outputs within reason and know that you’re getting a positive adaption. Yeah,

Paul Bouno: no, I really like that. One of the reasons I like that so much is because my population that I work with is autoimmune.

Like we’ve talked about that. Yeah. A ton. And I don’t know, like I’m writing these programs. I have no clue. Like not only are the training variables, so independent of one inter I guess individualized for everyone, but now I have a disease process to manage on top of it, which, like just even looking at lupus cuz that’s what I deal with.

So it’s a little, I probably know the most about lupus is there’s a huge chronotropic incompetence with lupus patients. Yeah. Like multiple studies, can’t get their heart rate up. So I can’t just prescribe breast interval based on any textbook, cuz like I have no clue. So that’s one of the reasons why I think some of your protocols are, have been so interesting to me because I feel as if all autoimmune patients should be actually trained as if they were professional athletes.

And I don’t mean that with volume and intensity, very intense monitoring of their training and these auto regulation protocols so that, on their good days, they’re able to maybe push a little bit. there’s also consistency there. Cause if they’re not feeling good, they’ll be able to hit the lower limit that was set for the day.

So that’s one of the reasons why I think this stuff is so interesting is because you can’t train them just like they’re gen pop, but they’re not gen pop. You know what I mean?

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And if you have someone who’s criminal trouble, again, competent, like I’ve worked with a few of ’em, whether they’re pots patients, autonomic DYS Somia, that type of thing.

Yep. We’ll have a spec for their min output and their min max heart rate, which is confusing. So if their max heart rate was 180 7 and today is a day where we’re gonna get after it, if they can hit say 90% of that one 70 and they’re putting in all out effort, cool. Then they’ll have a dropdown of just go do some aerobic work.

If it’s not there, it’s not there. There’s nothing that’s magically gonna make it happen. And so you can train a lesser output, but now you’re gonna get a worse output at a higher cost. And it’s just probably not a price you wanna pay on those days. Yeah.

Paul Bouno: Yeah. And that’s something that’s messaging that I think is gonna take me years to portray to the community because most the people that I’m dealing with, they don’t, no one wants to be sick.

You know what I mean? So like they wanna be trained like gen, like anyone else. So they wanna be able to jump into fitness classes and it’s like jumping into a fitness class when you have what I’ve read Mo even like a thyroiditis, like Hashimotos and like your metabolism isn’t regulating properly.

It’s that’s the worst thing for you? There’s no structure and there’s no way to track what you did. So you have no clue if your next training is more or less. And so I think it’s just really important to have these protocols in place for Autoimmune populations. I always wanna say compromised people, but that doesn’t sound very good.

, we’ll just keep it at autoimmune.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And the reality is the less overall, I would say, just anti fragile, less resilience you have, for whatever reason, you have to be more hyper specific on what you’re actually doing. So our elite level athletes are, not necessarily the most resilient, right?

Cause you’re walking that nice edge all the time of we, because you’re so advanced, we need to really push, volume, intensity, all these things, but it’s real easy to push you over the edge at the same. So paradoxically, like the elite of the elite, I would say are not super resilient per se.

Now there’s exceptions to that. If you’re looking at people have to play like, football games or repeat performance, but those performances are generally like more sub max, right? If you’re looking at you’re training for the Olympics, you’ve got four years to prepare for 100 meter dash, like they’re fragile athletes.

And I don’t mean that in any disrespect at all. But if you have an autoimmune issue, you’re you have less resilience. So you have to be more specific with what you’re doing, because the cost you’re gonna pay because you’re on that tight rope. If you go off woo. You pay a higher cost than other people are going to pay.

Yeah. So I would pitch it towards them. Because the way your body is set up, we’re actually gonna train you more like an elite level athlete. And here’s what that means. The reason for that is we have less capacity to get out this adaptation that we want. And if we misstep, you may have a little bit higher cost.

So what we’re gonna do is we’re gonna train you more like that to get you the response that we want at a lower level of cost. But then we’re also gonna do things to widen the base of the pyramid. We’re gonna do things that are gonna try to make you more resilient as a human being overall, so that when you do go to, Becky’s step class for 60 minutes or whatever, like you’re at a point where you can handle some weird shit in your life and it’s gonna be okay.

But we have to train you to get to you to that point. And just walking into that class day one, it’s probably gonna be a little bit too much, and you’re gonna pay a high cost for that, which then is gonna, erode the amount of time we could be training at that point.

Paul Bouno: Yeah, no, I think I guess I wanna tell a little quick story just, and it’s a little bit of a pat on my back, cuz it’s me.

I think it was 2000, 2019. I was in and out of the hospital with lupus and per carditis and cardiac tampanon for like shit five weeks. Yeah. Really gnarly.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Did they have to drain it, go in there and poke it? Yeah. So to speak. So

Paul Bouno: A little like a sub funny story. I went to my rheumatologist afterwards said, oh, you had 70 milliliters around your heart.

That’s a pretty, pretty good amount. That’s a lot. And I said, actually I had 700 milliliters around my heart and he was,

Dr Mike T Nelson: oh my gosh. That’s like heart failure, dude.

Paul Bouno: yeah, no I was baling out. I was they had to like rush in. Cardiologists to do an emergency surgery or they were like, I have like hours to live.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. So explain what it’s happen on is for people listening or we just geeked out on all this cardiac stuff real quick and then get back

Paul Bouno: to, yeah. Yeah. Okay. You have your heart muscle and then around the heart muscle, you have the peri cardio, which is aligning around that kind of lets the heart float within it.

Inside there’s like everyone has a little bit of fluid. It’s just natural that way. There’s no rubbing between the heart and the S however, with cardiac tampanon ends up happening is a ton of inflammation and fluid fills the sack and puts pressure onto the heart. So the heart has trouble contracting and pushing out blood to the rest of the body.

Pretty much, cardiac output goes down, stroke volume goes down, so your tissues begin to de-oxidize and all that good stuff. So it’s pretty, pretty bad. But, so that was 2019, 2020. I was back in the hospital a year later with per cardio fusion, same concept, but way less fluid. I caught it early.

So it didn’t exacerbate into cardiac tampon. Through that time, I had been just doing a bunch of zone, two training and resistance training to build the base of my pyramid to allow it to Make me more resilient and more robust to the natures of things. I’ve now been, I guess like a year and a half, almost two years, really with no issues, which is great.

I figured out a couple of the triggers for it and I’m doing really well, but this last weekend, Jen and I, and my fiance, we went on this hike and it was supposed to be a really easy hike while it was crowded. And on the way back, we’re like, let’s go on this different route. The LA there was a 90 minute uphill scramble.

Ooh. Like it was really steep. And we had two dogs, one with broken like a not broken hip, but really bad hips. It was a black lab. And so we are now scrambling my heart rate high for 90. And I’m like carrying my dogs through certain parts of it. Oh. And I was able to, yeah, we were able to recover from that very well, perform it and then recover from it.

No issues. Probably a little bit more tired this week, but that’s like the only thing that I’m really dealing with and I, my belief and what no one’s gonna tell me like, Hey, this is why is that? I’ve built in a bunch of resiliency since the first event. And even the second event of just building my aerobic training I’m on either the bike or the rower.

For about 150 minutes a week, three days a week for 45 minutes and then, doing resistance training the other days. And so like my belief is that has built up a bunch of resiliency to that activity, cuz just, after that issue in 2019, I had trouble walking. I, I would walk around my building for five minutes and I’d be like, winded, I’d have to sit down.

So I like my message that I always want to get across to people is that like you can build up a huge bank of resiliency by doing gradual progression into exercise and not like having these huge load spikes of all right. I’m released from my doctors. I’m just gonna go into a class and then get completely torch and come out saying like I’m intolerant to exercise.

It’s you’re very tolerant to it. You just need to progress in the appropriate volume and intensity over a long period

Dr Mike T Nelson: of time. Yeah. And that’s the. Beautiful part with exercise. You can almost always reduce the stimulus, right? You could use a lighter bar. You could. I’ve, like I said, I program people for 30 seconds on a rower, right?

You can get to the point where it is within your capacity to expand it. And that’s what to me is always fascinating about physiology is if your goal is to say bench 2 25, right? You can get stronger benching two 15 to 20, maybe 200. You don’t have to bench 2 25 because there’s a positive transfer to that.

Which to me is crazy. Cuz I think people think you have to go all the way out to the edge of your limits in order to expand them. It’s no, you have to go. Out to your limits, but you don’t have to cross them. You just have to get somewhat close and the body expands and your limits actually get a little bit better.

So it’s staying within that. And when you cross over ’em, if you don’t have the capacity of the resilience, you’re gonna pay a higher cost.

Paul Bouno: Yeah, no, I think that’s messaging that comes across, I wish came across on through Instagram,

Dr Mike T Nelson: but the reverse that’s not sexy.

Paul Bouno: yeah, like it’s not sexy and it’s unfortunate because, I am like, man, these methods are just making people worse. The ones that are just like, Hey, every day you’re grinding or whatever. It’s man, I’ve ne in the last year and a half, two years, I’ve been like, I have not had one workout where I was like, I’m grinding.

It’s I’m working really hard, but I’m definitely working within my limits. And I think that’s really important for people to understand.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah, to me, it’s just the. The number one thing is just do something halfway intelligent and number two would be just violent consistency. Yeah. Like just show up again tomorrow and yeah, the discipline aspect of it is actually listening to your body and doing what’s best for you that day, which I know for me two days ago was like, oh, screw this.

I’m just gonna go kite boarding. Woo didn’t train at all. that was great. It was like exactly what I needed. Got some movement, got to do some fun stuff, got to be outside, and some days it’s. Yeah, it’s not really here today. So I’m just gonna walk out halfway through the session and spend 20 minutes and go stare at a tree and meditate, that’s not sexy, but to me that’s being very disciplined to do it versus, just try to do something heroic, looking for Instagram.

Paul Bouno: yeah. I I wish more people understood that and I think there would be a completely different, know, people would get more results. People wouldn’t be nearly as banged up in the gym or in life. But yeah, so like that’s just, it’s really cool to me to see a lot of the stuff that you put out and done through like your flex diet certs.

I’m excited to go through your HR V course, because it really comes down to. Auto regulation. And I love the word, but I also sometimes hate it. Cause it confuses people. But it comes down to just having the protocols in place to manage your tr your training sessions based upon where you’re walking into that training session or even that training week.

I figure your stuff has been really helpful for me as your iron intern, as you said, and just like continuing to learn through it.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Thank you. I appreciate that. And it’s yeah it’s hard to figure out that line between. Man. I just don’t feel like doing this versus is the performance not there?

Can I alter it? Having the experience to know how long does that take? Like even the session I did the gym yesterday was like, oh, it was late. I was tired. I didn’t wanna do it. But, I just ah, just show up, go through the warmups and yeah. To modify bench and do wait less than what I want, but got a few more reps.

And then, it took me about 35 minutes to get into the session where it felt pretty good and ended up getting a volume PR in the Saxon bar, which is a weird pinch script thingy, minute 10 in the session, I would’ve thought it was gonna be dog shit. But it’s no, just do a little bit better.

I’m like, oh, next step was a little bit better. Oh, next step was a little bit better. So it was, the diesel engine warming up and some days those are longer, but sometimes those turn out to be good sessions too. Versus, there are times where you’ve given it your best efforts for 30, 40 minutes and there’s definitely.

Nothing there. And you’re well, sub max of even your baselines. Yeah, probably a good time to leave at that point, but it’s the discipline of trying to figure out, when to stay and when to go and that you just only learn that by just being consistent in time. Yeah.

Paul Bouno: Yeah. I was gonna say it just takes years.

It takes years and years of practice to know like what you should be doing on any given day and when to throw in the towel. And when throwing in the towel, like throwing in the towel for one day does not mean you quit. It just means like you can come back and do better the next day or a couple days later.

People are so afraid of the stopping a session early. I remember years ago there was a CrossFit athlete a games athlete and he was getting interviewed and he was like, and so I was like, have you ever quit a session? He’s I’ve never quit a session. I’m like, you’re an idiot. You, there’s probably a ton of sessions.

You should have quit. And now a couple years later, he like can’t compete anymore. He has knee tears and he like herniated. He like tore his shoulder. I’m like this is what happens when you never leave a session.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. So it’s gotten has a great book called I think it’s called The Dip.

It’s about basically strategic quitting, and the takeaway from it, it’s a great book. I’d highly recommend people read it is you probably don’t wanna quit when you think that you should, but consequently, just forcing yourself to the end is not the best decision either. So how do you pick a point where you’ve clearly given it enough ample opportunity and know that it’s not working and still pull the plug on it?

Cause at some point there’s. There’s some cost fallacy where this isn’t business all the time and I’m guilty of it too. Oh, I’ve invested like nine months into this project. And no one buys it, nobody cares, but I’ve invested nine months into this, there’s this investment cost.

But if it’s not working, it’s not working either, but that’s yeah. Humans are wired to make hard decisions there. Not easy.

Paul Bouno: yeah. Yeah. And always, I feel like it’s really tough when it’s around time or money too. It’s man, my money and my time and especially time it’s like, like, I can’t get that back.

It’s you’re not gonna, if you don’t leave now, you’re just gonna lose

Dr Mike T Nelson: more of it. So I know, and I have a hard time with that. I did a whole project. We filmed it, everything, set, everything up, wrote it with another guy. Did it last September? Luckily I set up the contract, so I did get paid for some of the filming and some of the IP we put into it.

Long story short said, company went under guys trying to sell it. Now probably won’t get any takers. So there’s a high chance of, I don’t know how many months worth of work and filming. And it’s literally done. Like it’s literally edited. It’s professionally shot. It is literally finished and we’ll probably never see the light a day and that it just, and part of it’s yeah, of course that’d be nice for an income stream, but part of it’s like you put so much time and effort into it and you want to see cuz you think that it’s gonna be useful to people.

Your assumption is that it would be, but then there’s other thing of even if we got the rights to it and all that kind of stuff, do I have the bandwidth to go in that? Cause it’s a little bit different direction than what I’m doing now, just to see, so there’s all these other things I’m trying to be more aware of, but it’s still nags at me.

It’s oh, all this effort. And it’s just sitting on some dude’s hard drive somewhere.

Paul Bouno: Yeah. Yeah. I had a project a couple years ago. Very similar. We had a ton of it done professionally done. The whole thing was supposed to be a nutrition tracking app with video, but more of the story just push came to shove and we went separate ways and it’s just tough cuz it’s all that work is sitting there

Dr Mike T Nelson: and

Paul Bouno: I thought it would’ve been good.

I still think it would be good,

Dr Mike T Nelson: but it is what it is. Yeah. So for people listening, this applies to your programming to like complexity is the death of compliance. If you, things are too complex and your compliance is going down, like just simplify it. Another buddy of mine, Josh said just simplify until you can.

So I even look at client’s programs. If they’re not able to do it, yeah, I’m interested in what the reasons are in working through ’em and stuff, but I’m probably gonna make it more simple. If it was too complicated, just make it more simple until you can do it and that’ll be better.

Cause I have a tendency of making things more complicated than what they should be, just because, oh, they’ll think I’m such a great trainer now. Blah, blah, blah. It’s but they’re not doing ’em it’s not helping them. So at the end of the day, you might need to simplify more and avoid some complexity.

Paul Bouno: Yeah.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Couldn’t

Paul Bouno: agree more. I’m very guilty of that as

Dr Mike T Nelson: well. I think everybody is

cool. Thank you so much. Yeah. Thank

Paul Bouno: you. It was really helpful. And I’m excited to listen to it probably over and over again so I can keep getting the answers to some of my questions and all that

Dr Mike T Nelson: stuff. Yeah. And where can people find more about you if they’re made it this. Yeah.

Paul Bouno: My Instagram is@paulbono.com.

And then

Dr Mike T Nelson: how do you spell that? Just so people who are bad spell owners

Paul Bouno: it’s P a U L B U O N O. And then my website is Paul bono.com. So same thing. So pretty easy to find me no hidden, hidden ways.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Great. I’m Dr. Mike Nelson, this goes out to your audience, just Mike nelson.com. Instagram is Dr.

Mike T. Nelson. So D R M I K E T N E L S O N. Thank you very much for all the great questions. I really appreciate it. Yeah. Thank you. I had a really good time chatting. Cool. Awesome. Yeah. Thank you so much. That was fun. Hopefully that was useful for you.

Paul Bouno: Yeah no I think it’ll be really useful. I think like I, some of the stuff around, I always get in the weeds with setting up like training weeks and things like that.

And I overthink so much, especially, all my populations just very basic or whatnot, but I’m always worried about creating some type of load spike or some type of too much training monotony and leading to, overuse injury because of it. So it was really helpful to hear some of this stuff and continuing to work through it.

Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And if you have lower level athletes, like it’s just harder to get a load spike. Like they just don’t have a lot of capacity. Yeah. But it’s only once you start scaling capacity and volume with higher level people that it becomes, I think more of an issue. Yeah.

Paul Bouno: Yeah. I just gotta, I gotta like always remind myself the context of who I’m training and it’s it’s tough because for years it was all these high level athletes.

And I needed to really think about these things and be very wary of, load spikes and setting up the week around, perfect training. And it’s like half the people that I’m training aren’t even training harder. Like even if I wrote the design to be really hard, they wouldn’t even train it hard enough to get like the response.

So it would just be, ah, it’s, it was fine. And it’s what do you mean? It was fine. It was like 30 seconds on 30 seconds off. It’s supposed to be brutal. Yeah. They’re like, oh, it wasn’t too bad. I’m like, okay. So yeah. Yeah, but yeah, like one thing is I’m always trying to figure out now, like the different systems of even putting like an anaerobic interval after our resistance training day.

Like what, where does that fit in? And when to do it, when not to do it.

Dr Mike T Nelson: but yeah, I’d say most of time, you’re fine. Like high intensity train, as is more close to resistance training. The adaptations are pretty similar. The biggest problem you have is just quality of work, and then most people I find if they’re general, not at a high level, they didn’t really work hard enough during their lifting to really affect it at all.

Anyway. Totally. If you’re training some, anaerobic monsters then yeah. You probably can’t do their high intensity training after like day, but yeah. You’ll know that when you do it, once you just their power output shit. Oh, okay. Oh, that was a bad idea.

Paul Bouno: that’s true. Yeah.

Dr Mike T Nelson: It’s cool to

Paul Bouno: Have these metrics around testing and their power output cuz you’ll know, I’ll know their max and you know what they’re capable of and it’s Hey, you didn’t even come within 90% of that.

Like you were te like over 10% away, that’s you’re pretty far away.

Dr Mike T Nelson: So stuff like that, but yeah. Thank you. Yeah. Cool. Sounds good. And I’ll send this over to you probably later today and we’ll talk to you soon and best of travels. Cool. Thank you. I really appreciate it. No problem. See ya. Bye Mike.

My.

Thank you so much for listening to the podcast today. Really appreciate it. Big, thanks to Paul for all of the great questions, an awesome discussion there. Make sure to check out all of his information on Instagram and his website. If you’ve enjoyed this, then you wanna do a deeper dive into ways to become more resilient, robust antifragile, increase your aerobic base and just generally be much harder to.

Check out the physiologic flexibility, cert go to physiologicflexibility.com for all of the information right now, depending on when you listen to this, it may not be open, but put your name in there to get onto the wait list for the next time that we open it. And I will be able to get you all of the information.

We normally have a couple fast action bonus items there. Once it opens. So that’s the physiologic flexibility cert if you’ve enjoyed the flex diet cert, which is based on metabolic flexibility, it’s a similar idea, but I expand to the concept to include you as an entire organism, but this includes everything from cold water and heat adaptations to pH changes to a big, deep dive into ketogenic diets. How I do believe that there is a role for them, but there’s a bunch of caveats you want to follow carbohydrate use to the highest degree for high intensity exercise and how to manage oxygen and carbon dioxide. Just by doing a few of these action items. Most of the time, it doesn’t take a ton of time either to add them.

Your program or your client’s program? We have seen a huge improvements with just a few more items that you can add in, or sometimes even just combine into your training and replace some of the other work that you were doing. So go to physiologicflexibility.com. Thank you so much for listening to this podcast.

We really appreciate it. If you have time drop us a very. Review and whatever your favorite podcast app is, we would love it. Reviews are obviously extremely helpful to move up the old rankings and get more people to listen to it. Thank you so much. Appreciate it as always talk to you next week.

Leave A Comment