In this episode, I had the pleasure of delving into the intricacies of metabolic flexibility and physiologic flexibility. Over decades in the nutrition and performance realm, I’ve gathered a wealth of knowledge, and it was a privilege to share some insights.

We dove deep into how enhancing metabolic and physiologic flexibility can significantly boost your resilience and performance as a human being. It’s all about adapting and optimizing our body’s ability to handle various stressors efficiently.

Heart rate variability (HRV) emerged as a crucial topic in our conversation. I highlighted how wearable technology can be a game-changer in monitoring and enhancing recovery by tracking HRV data. We delved into practical tips for interpreting HRV metrics accurately and discussed strategies for adjusting training and lifestyle to ensure optimal recovery.

Overall, it was an enlightening discussion filled with actionable insights to help individuals maximize their potential and lead healthier, more high-performing lives.

⏰ Episode Timestamps

- (0:00:00) – Ultimate Guide to Nutrition and Wellness

- (0:04:01) – Metabolic Flexibility and Nutrition Discussion

- (0:17:07) – Nutrition and Training for Athletes

- (0:25:25) – Adapting the Body for Survival

- (0:37:38) – Optimizing Physiological Adaptation in Athletes

- (0:49:40) – Heart Rate Variability and Stress

- (1:00:53) – Information on Dr. Mike T. Nelson

🎧 Listen Here

Rock on!

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

0:00:00 – Speaker 1

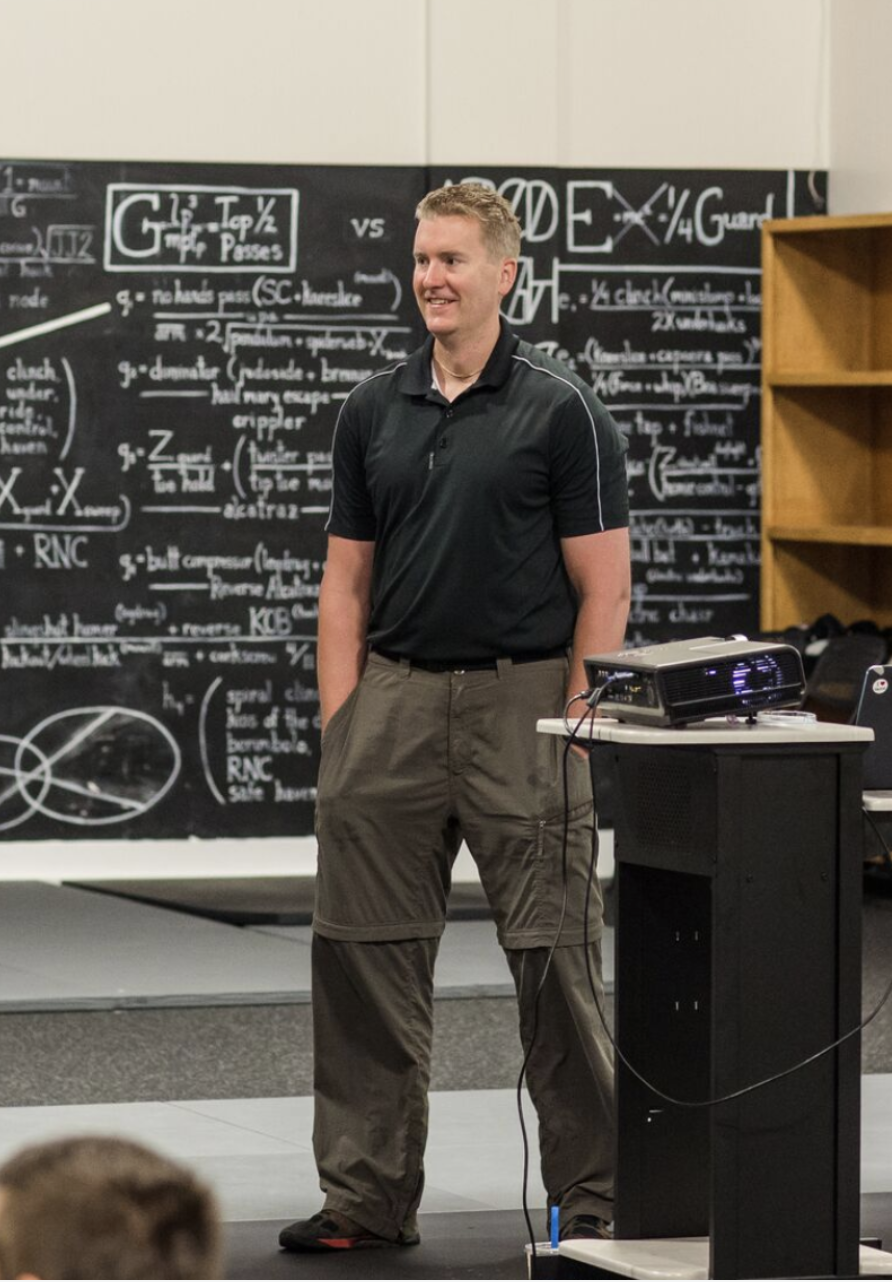

Welcome to the Achieve Results Nutrition and Wellness podcast, the ultimate guide to feeling and looking your best. Join me, your host, as we embark on an exciting journey to discover the power of nutrition, exercise, sleep, recovery and mental performance. Get ready to be inspired, motivated and uplifted as we uncover the secrets to unlocking your full potential and living your best life. Whether you’re a fitness enthusiast, a wellness warrior or just looking to improve your overall well-being, this is the podcast for you. So sit back, relax and let’s get ready to elevate our performance together. We are back again today with another incredible guest. This one’s a multiple, so bear with me as I get through it, but this guy has earned every single one of these accolades, so I want to make sure I get them right. Alright, so I want to introduce you guys today to Dr Mike T Nelson, phd, msme, cscs, cissn and Mike as a research fanatic who specializes in metabolic flexibility and heart rate variability, as well as an online trainer, adjunct professor, associate professor at the Carrick Institute, presenter, creator of the Flex Diet, cert, kiteborder and, somewhat incongruously, heavy metal enthusiast. So Mike does a lot of stuff. Mike’s a busy man, so he has a PhD in exercise physiology and a master of science in mechanical engineering biomechanics. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines and scientific publications and on websites across the globe. In his free time he enjoys spending time with his wife lifting odd objects, reading research and kiteboarding as much as possible. You can find more out about Mike at his website, wwwmiketnelsoncom.

Okay, dr Mike T Nelson, welcome to the podcast. My friend Hi, how are you doing? Man Great, can’t complain. Dr Mike, tell us a little bit. Just give us a quick intro for those of you who don’t know you, we got introduced to your laundry list of accolades and whatnot.

Let the people know a little bit more about what you do and where you came from, and then we’ll get this thing off and running.

0:02:21 – Speaker 3

Yeah, so I knew a variety of things probably more on the nutrition side, I guess you would say for exercise, physiology nutrition, mostly for performance and body comp. I’m an associate professor at the Carrick Institute. I work with some clients through my own business, extreme Human Performance, some other clients through Rapid Health with Dan Garner, dr Annie Gelpin, anders Doug, all those guys over there Just working with the ketone company with Hekton they’re looking at a new ketone ester. So trying to help with some of the studies Like how would you look at everything from performance all the way through potentially pathologies, concussion, traumatic brain injury Just pretty interesting.

And yeah, finishing up a triphasic two book with Coach Cal Dietz, which I’m not sure when it’ll be out, but hopefully sooner than later. That’s super excited. It’s all new material which will be fun. I’m just excited for it to be out because it’s been a extremely long process. And then doing a book on metabolic flexibility for human kinetics with the Janna is the RD on that. And yeah, haven’t been out kiteboarding much this summer at all. We’re down in South Padre for over there for four weeks in spring, which is pretty fun. I hit my goal of a 20 foot jump. My little measuring device that, as I had 26 feet, which I’m not sure if I really hit 26 or not, but I’ll take it. It’s generally relatively accurate and, yeah, still living, working on picking up the Thomas inch dumbbell, hopefully within the next probably two to three years, somewhere around there.

0:03:57 – Speaker 1

All right, there we go. Good, I like that you got the long-term goal set.

0:04:01 – Speaker 3

Yeah.

0:04:01 – Speaker 1

And you’re working on the book with Janna Massey. I guess she’s married now.

0:04:08 – Speaker 3

But, yeah, that’s why I didn’t see her last time, because I don’t know if she’s officially changed her last name. I should probably figure that out. I just asked her. I talked to her the other day. Amazing, good deal.

0:04:18 – Speaker 1

That’s really cool. I’m excited for that one to come out and that’s what I wanted to really dive into it off the start. Today is this topic of metabolic flexibility. I know you are the guy when it comes to metabolic flexibility and you know teaching it to people and your understanding of it. So I would love just to dive in into like just exactly what is metabolic flexibility, start there and then maybe kind of transition that into what is it and who it’s for. How would best serve people?

0:04:47 – Speaker 3

Sure, like in fitness especially talk about nutrition. Everyone wants to have an argument about what the best macronutrient is, which to me seems like such a bizarro type argument is the other people of oh no, carbohydrates are bad, they’re evil, they’re going to kill you. And then you have the opposite of how. You need carbohydrates for performance and you need really high amounts of carbohydrates, and there’s still some stuff floating around about. Too much protein will cause your kidneys to flat of your back and to their side of the room and damage them. And it just seems like everyone wants to vilify one thing or the other.

Is the way to write a diet book? Just vilify gluten or even, for God’s sakes now, vegetables or whatever is going to be next, and then you can sell a diet book. And there is a little bit of truth to some of those things, right? Is it from working with lots of clients? Yeah, I’ve had some clients who vegetables didn’t really go very well due to digestive issues. Does that mean I’m going to tell all my clients with good digestion oh, vegetables are bad, don’t eat those horrible things.

Now, that doesn’t make any sense. So, with metabolic flexibility, if you just narrow it down to the two main fuels you’re using. You have carbohydrates on one end, fat on the other end, the metabolic flexibility of how well could you use carbohydrates under certain conditions? How well could you use fat for energy and performance under certain conditions? And then how well can you switch back and forth between the two? So you’re looking at carbohydrate use, fat use and then switching back and forth between those. So you’re trying to respect more what’s actually going on with physiology instead of just demonize one whole macronutrient group.

0:06:29 – Speaker 1

Amazing, yeah, and can you touch more on the switching back and forth, because I think most people understand, like all right when I’m more active, I’ll be utilizing more carbohydrate. When I’m more at rest, I may be utilizing more fat. But how do you create a situation where the body is able to actually switch from one to the other, or where you, when you need it, to switch from one to the other?

0:06:52 – Speaker 3

To me how well you can switch or move from one thing to the other thing is one of those principles of physiology is not talked about it much, so I got some just HDR human dynamic range. So if you imagine that carbohydrate use and fat use are like a barbell, we want to expand the spectrum out as far as possible and then we want to be able to move back and forth between the two. So an example would be let’s say you just had a huge high carbohydrate meal, so your body is going to switch to use carbohydrates mainly as a fuel. But once it’s done that, how fast does it get back to baseline, which would be more of a fat use? Because, let’s say, you’re not lifting at that point, you’re just hanging out, watching TV or whatever.

If we have someone who maybe is metabolically inflexible, maybe a type two diabetic or they’ve got some metabolic issues, you’ll see that they hang out there longer and it takes much longer for them to come back to baseline. Sometimes they can’t go up as high either. So in studies what you’ll see is that it takes longer for them to reach sort of a peak. The peak of which they hit will be lower. So the response is squashed and that curve gets flattened out. So they end up staying and using carbohydrates a little bit longer, but they actually don’t use them as well or as effectively.

It’s very similar to if you look at an Oroglucose tolerance test. We give you a whack ton of like 80 grams of glucose. You’ll see there’s a big spike and then you’ll see it gradually a couple hours come back down to baseline. That’d be a normal response and some people that peak may be a little bit too squished or it might be super spiky and they’re just dropping too fast or they’re taking forever to come back down to baseline.

It’s a similar idea that you want to be able to upregulate as high as you possibly can and then when that is quote unquote done, you want to be able to come back down to baseline again. It’s very similar to heart rate. If you’re doing, let’s say, some horrible 20 rep front squats, your heart rate is going to be elevated super high as you’re resting. You want it to come back down to baseline faster, or heart rate recovery. So it’s a very similar idea of you want to be able to respond to the stimulus as it’s presented and then, as it’s run its course, you want to be able to switch and get back to the next thing. That’s going on, perfect, yeah.

0:09:19 – Speaker 1

Amazing and I guess my question is because the majority of my audience is more like general population, just people in the fitness world trying to eat healthy or live that healthier lifestyle without the ability to measure this stuff. Is there any actions that you would recommend taking, or is there any way for people to know if they actually are becoming more metabolically flexible?

0:09:39 – Speaker 3

Yeah, so the two things that I use is sort of field tests that anybody can do. They don’t have equipment and they’re not going to prick their finger and take measurements or do all sorts of. They’re not weirdos like I am and have a metabolic card at their house in their garage to do a bunch of testing that costs thousands of dollars and stuff. On the carbohydrate side, I call it the two pop tart test. Can you have for breakfast two pop tarts and then simply, how do you feel If you feel like you’re going to take a glucose insulin induced nap under your table for two hours and you can’t string two thoughts together? Probably not the greatest that using carbohydrates Another in the spectrum for fat use can you do about a 19 to 24 hour fast and feel pretty good? Go about your normal days, maybe do some moderate exercise? Yes, you’re probably going to be hungry, but it would look from the outside relatively normal ish. If you can do those two things on the carbohydrate and the fat side, odds are you’re probably pretty metabolically flexible.

0:10:38 – Speaker 1

Yeah, perfect, I love that and I think that’s one way that I like to think about it is I guess I explain it to people as well. Do you feel like you must eat every two to three hours? Yes, like angry going crazy, like mood swings or energy highs and lows, or things like that. Then you probably know that you’re not super metabolically flexible, right, yeah, and that gets into the transitions.

0:11:01 – Speaker 3

The theory is that you probably can’t transition or downregulate to use fat quite as well and, like when the system is really dysregulated, you get kind of stuck on the glucose side. We normally have another alternative fuel to use. Really well, we don’t really can’t tolerate these kind of drops and blood glucose. So let’s signal the brain and the body to be like hey, just eat more carbohydrates. That’s a working theory and that gets into whole models of appetite based on lipostatic, which is a fat model, and the carbohydrate model, and the truth is it’s probably somewhere in between. But in practice I see the exact same thing you said, like someone who’s mad. I eat every two to four hours or I get really high angry and I get mad and I just don’t feel good.

0:11:43 – Speaker 1

That’s, that’s not normal, yeah absolutely, and what do you recommend for people that are in that situation? Are you going to go to a more fat adapted diet for a little while higher fat or are you going to push them in terms of cardio based exercises? What’s your go to?

0:12:00 – Speaker 3

Yeah, there’s a bunch of things you can look at. On the macro nutrient side, I’m probably going to reduce carbohydrates to start with, so we’re going to remove the thing that they’re having a little bit of reactivity to. Like you said, you can play around with adding a little bit more fat. You could play with more fiber, more protein. Usually, more protein definitely seems to help quite a bit for most people. Once you’ve done that, then I’m thinking okay, why are they having these sort of weird things? If I’m able to use technology, I’ll look at heart rate variability to get an idea of some stress levels or just self-report. Do you feel stressed? Because that’s going to slam them more towards that sympathetic stress side which is going to keep pushing them towards carbohydrates to alleviate that stress.

Sleep is a big one. How long are they sleeping? How good is their sleep Digestion? The other thing I wish I would have done sooner is actually looking at. I probably did a pretty good job of looking at overall muscle mass. If I had more muscle, that’s probably going to be a better position than less Body comp is going to play into that. The thing I wish I would have looked at sooner was VO2 max or just their aerobic fitness level. What I’ve noticed in a lot of those people is it’s quite low sometimes, and the analogy I use is I don’t know, you might be old enough to remember the Ugo, the little three cylinder car that was like a squirrel in a shoebox. It was pretty horrible.

The Ford Festiva, or the Toyota Yaris you’re a tall dude like these tiny little cars that look like a clown car.

0:13:28 – Speaker 1

Yeah, sorry to cut you off, but I used to ride to school every day in a Ford Festiva.

0:13:32 – Speaker 3

Oh, there you go yeah.

0:13:34 – Speaker 1

Grade 10 through 12, buddy, my best friend, that’s what he goes. We had I was 6’4″, he’s 6’3″. We had a body that was 6’6″ and another one that was 6’5″ and we all used to fit in that Ford Festiva somehow. I’m not even exaggerating.

0:13:47 – Speaker 3

Oh my gosh, that’s crazy. Did you have a sunroof where you just stick your head through the sunroof fan?

0:13:52 – Speaker 1

Well, now it had more space than it looked, but yeah, sorry. Anyway back on track now.

0:13:58 – Speaker 3

Yeah, no, totally. If you have a very small V02 Max or a small aerobic engine, it’s just generally going to be quite difficult compared to if you have a bigger aerobic engine. You’re just going to use a lot more fuel. Odds are your partitioning is going to be a little bit better too. So the analogy I use is if I take my little Ford Festiva, I can redline it and get to the grocery store, but I’m going to impart a huge amount of stress just to get an average performance out of it, compared to if I have a Corvette engine. Probably get the same speed with a fraction of the RPMs, so I can get to the same end result, but I’m doing it at a fraction of the stress level too.

0:14:38 – Speaker 1

Yeah, I love that and I think that’s is like you said. That’s the thing that you notice to people who have the muscle mass, I think is the biggest thing, because that’s actually the housing for all of this stuff. If we just want a bigger garage to essentially stuff all this extra whatever blood carbohydrate, dietary fats and things- that we’re much bigger sink.

Yeah, totally Like. That’s obviously going to be the winner in most cases there, because it does create a ton of flexibility for people and it also creates a better ability to like overeat at times and not have such a drastic call it, a negative effect or a bounce back effect from those larger meals.

0:15:11 – Speaker 3

And then yeah, the max is huge.

0:15:13 – Speaker 1

Again, I think that’s going to play a really big role into the way that your body is utilizing the nutrition that you’re putting into it.

0:15:20 – Speaker 3

Yep, I agree, and yeah, I was going to say something on that, but I think it’s just that both of them are useful. This depends on what angle you’re looking at it from. Imagine someone who has a lot of muscle versus not much muscle and they both go for a walk. The person who has a lot more muscle is literally going to use more fuel just to go for a walk. If you have a bigger engine overall, bigger chassis, bigger frame, you’re just going to burn a lot more fuel and the more I think you can pull energy through the system at a higher level or kind of a higher flux rate, just everything else just seems to work better. So for people listening, if you can be weight stable at maintenance on 3500 calories a day compared to someone else who’s at 2000 calories per day, yes, calories matter. They’re both weight stable, so calories in and calories out are equated. I would much rather go with the 3500 in and out per day, like you’re just moved so much more energy through the system, just a lot of other things just work.

0:16:19 – Speaker 1

So much better. Yeah, so you’d rather be the gas guzzling truck than the Prius in this case? Yeah, definitely All right, good stuff, man. Yeah, I think that’s awesome. So hopefully that really helps people understand the metabolic flexibility, because I do get a lot of questions about that Just in the diet world. I think it’s something that’s becoming a pretty popular topic. A lot of people are starting to. I know you’ve been talking about this. I met you in Costa Rica, what six years ago, and you were on it.

You were heavy into it at that point. Even so, I know you’ve been on top of this stuff for a very long time, but I think it’s one of those things that’s certainly starting to catch some steam. People are starting to think about this stuff, right.

0:16:58 – Speaker 3

Yeah, which is great. I started looking at it 15 years ago. It seems crazy to think about.

0:17:04 – Speaker 1

Yeah, exactly no, that’s awesome. I did want to talk about on that topic as well is where does this fit? I think we’ve explained where it fits in terms of just general population. We just in terms of health. This is a really great way to improve people’s health and their ability to utilize their nutrition properly and not run into blood sugar issues and things like that. Where does it fit into the more athlete and just very active person population? Are you recommending whatever the high carb high protein meals around training and then high fat low carb meals and whatever high fat higher protein meals outside of training to somebody who’s burning a lot of energy on a regular basis?

0:17:46 – Speaker 3

Yeah, for those cases with more of the athletes, I would say a general template I use is higher protein, around 0.7 grams per pound of body weight. You could scale up to one gram per pound of body weight. I think that’s fine. Dietary fat total per day 50 to 80 grams somewhere in there. Sometimes people will hit 100. It’s lower, but it’s not so low. It’s going to screw with your hormones and you’re spraying everything with Pam and eating egg whites and making your life miserable. You can have some fat, it’s going to be okay. Yeah, and then I’ll titrate.

Carbohydrate amounts to depend on their goal of body calm versus performance. If their goal is just all out performance, it’s bro. Just eat as many carbs as you can. Now, if body calm starts going south, we’re going to have to pull back on that a little bit. And then if they’re really the weight class athlete where they’re really trying to maximize body comp and performance, then I start getting into prioritizing carbohydrates more around, like the heavier lifting days or high intensity training. So I’ll split.

I use a lot of times is lifting or high intensity work Monday, wednesday, friday, some cardio type stuff. Tuesday, thursday, saturday, sundays typically just a complete off on low day, just do a long walk or a nice hike or something like that. In those cases, if they’re really trying to push body comp and performance, I will have higher carbohydrate amounts Monday, wednesday, friday ish, and then lower amounts Tuesday, thursday, saturday. I may even do who gosh like some fasted cardio, low intensity on the mornings in those days. So we’re trying to up regulate fat use a little bit more on those days, get some recovery in. We don’t want calories so low that we’re going to impede recovery, but we have a limited amount of carbohydrates to spend, so I’m going to try to spend those per se more on the days where they’re going to be using more carbohydrates.

So a little bit more fueled for the lifting sessions and then, if you really start having to really crush calories, I do find that nutrient timing does appear to be more beneficial than so. We initially will have more carbohydrates leading up to the session. I could be the night before, it could be the morning of, just depends on what’s going on. So you want to have good muscle glycogen, that’s restored. Maybe some carbohydrates during the session, depending on the goal, depending on how long it is, maybe some after, and then after that point we’ll probably pull back on them a little bit. So it’s just like kind of, if you have a certain amount of budget, how much are you going to spend and what is the most realistic place to get the biggest bang for your buck to spend them?

0:20:26 – Speaker 1

Yeah, awesome, I love that and that sounds like it would be pretty standard across the board. Obviously we’re talking athlete population there, but even just general population too right For somebody who’s maybe they’re only able to train I don’t know call it Monday, wednesday, friday, saturday or something like that just due to like work schedule and kids and life and whatnot. So in that situation would you pull just like a similar process there, just reduce the carbohydrate on the off days, kind of thing?

0:20:51 – Speaker 3

Yeah, especially if their goal is body comp. It’s funny like the more I worked with I worked a lot of general population in the past, not as much now, but a lot of the work with athletes and general population you can probably speak to this too isn’t really that different. The concepts are literally the same. Now the amounts and what they’re doing and the level of detail you get to. Yeah, those are sometimes completely different worlds, but the ideas and the concepts don’t really change that much.

And what I found was the extremes and form, the means. So even now, like I’ll program for a very high level athlete and then if someone is more recreational, even just getting into the sport, I’ll just start pulling stuff out of their training and I can get back down to a moderate level. I can’t really take a moderate level and try to scale that up to an elite level athlete. Just doesn’t seem to work that well, right? So as a tall dude, you know this. When you use exercise equipment, like the new rule of exercise equipment is, let’s make it as well as possible for very short people and very tall people Anyone in between it’ll be fine. For if we try to make it for this stereotypical male five foot 10, anything outside of that is just going to suck. So if you design for those extremes, the mean in the middle will take care of itself.

0:22:11 – Speaker 1

Okay, perfect. Yeah, I love that. And I guess my the only other question there. I keep flip flopping back and forth and I know you said like it would depend on the goal and like performance was the main goal or whatnot. But do you worry about impacting recovery on off days for athletes If you are stripping away some carbs, or is that just par for the course? It’s just part of the deal, because you got to do what you got to do.

0:22:33 – Speaker 3

Yeah, yeah, I mean if in a perfect world, right there, you would find the happy balance where their body comp is fine and then you wouldn’t really cut carbohydrates on the recovery days, right? Because I what I’ve noticed is at some point it’s not a linear thing where in a perfect world is someone’s hey, you know, I want to gain a couple pounds of muscle. I’m a natural athlete. I’ve been training for two to four years already. Yeah, in those cases, like I just do almost the same thing every day, whether you’re training or not, because I find that beneficial you’re going to need the fuel, etc.

Where it gets tricky is when you’re talking about body comp. Now you’re trading off performance on one hand, body comp on the other side. It’s like walking the tightrope, like you’re trying to find the happy medium and unfortunately it’s just different for everyone. Like I wish I could give a formula based off of someone’s ffmi or just muscle mass and be like bro, you definitely need 300 grams of carbs this day and 120 the next day, and it just doesn’t work that way. Like I’ve had athletes who are literally almost the same size in the same sport on the same team and their carbohydrate amounts may be 100 to 200 grams different per day, and you’re just like. That just seems to be the way it goes.

0:23:49 – Speaker 1

Yeah, wouldn’t life be easy for people like me and you if there was just a template.

0:23:52 – Speaker 3

Yeah, and I think with protein you can get pretty close. Fat you can get close, but I don’t know. Like carbohydrate amounts, just it varies widely. I have a pretty high level. Obstacle course racer were off season. He’s very lean. We got up to 450 grams of carbs per day. I think his peak weight was 160 pounds and I’ve got athletes that are twice his size on half that amount of carbohydrates. So it’s I don’t know.

0:24:22 – Speaker 1

Exactly. Yeah, hey, that’s where you come in, yeah, it’s where the pro comes in. So, no, that’s great man. I think that that explains things really well and people will have some usable, I think, info and tools to take from that. So the thing that I wanted to get into pretty we’ll see what we got time for today pretty extensively, though, which is super interesting to me I don’t know if it’s new, but your concept of physiological flexibility. So can you just explain exactly what you’re referring to when you’re talking about physiological flexibility?

0:24:53 – Speaker 3

Sure. So after I started working on metabolic flexibility about about 15 years ago, probably, maybe four or five years after that I started thinking I’m like, okay, so that’s cool for metabolism, you can expand metabolic flexibility to include lactate and ketones and other intermediates, et cetera. But what about if we take that idea and we scale it up to you as just a physiologic organism? Okay, so what framework am I going to use? So what do I? How do I believe that the body operates? And my bias is I believe the body operates basically off of survival. Your body is literally wired to do everything that possibly can in order to survive, and even if you want a higher level of performance, you just generally have to teach the body to survive it better. It was the whole point of adaptation exercise, all static load, blah, blah, blah, all these fancy words. But then, to the day, there’s backup systems to the backup systems, to the backup systems, to the backup systems. Right, because your body still has to function and it’s trying to keep you upright. Like to me, it’s fascinating that very minor details and elite level athletes can make a huge difference. Now, granted, you’re talking about tends to you know, hundreds of a second make a big difference so that, okay, I got it. On the other end of the spectrum, you could probably live on 711 slurpees as your only, as your only meal every day for months to maybe years Now. Would you be healthy? No, is that the best thing to do? Absolutely not. I don’t recommend anybody run that experiment. But using people’s dietary logs, you’re like bro, how long you’ve been eating this way? They’re like I don’t know most of my life. The fact that they’re there talking to you upright with some semblance of health is just fascinating. If I put sugar in the gas tank in my car, I’m not even gonna make it around the block, right. So the extreme nature of what the body can tolerate is just fascinating. Now there, insulin may be all whack. They might be type two diabetic. They’re definitely going to have some issues going on. But so if the body survival based, then we’re. We have the basic stuff covered. So sleep is good, nutrition is good, exercise is generally good.

What is the next level Like? How do you come up with a framework or systems? You can tell, my background was also in engineering. That allows us to evaluate all the other bazillion different things that could be coming out people. So I put red light on my ballsack. Do I do this breathing technique? Do I do the supplement? Or this super food that’s only harvested in the Amazon by local people there, with piranhas stuck to their ass, like once a month? Or all these crazy things that, like, the fitness world comes up with, like how do you figure out? What framework can you use to decide what is that sort of next level?

Again, if we go back to survival based I looked at what systems then in your body does it have to hold constant, and if it doesn’t hold constant, you’re dead. And you come up with temperature. When humans are homeotherms, we have to keep around 98.6, effective, about 97.7 degrees Fahrenheit internal body core temperature. If we don’t do that, it varies even just a few degrees, you’re dead. However, we have these huge amount of adaptive capabilities to tolerate warmer temperatures, especially due to exercise, environmental conditions, colder temperatures, even with the absence of technology, humans probably the only real advantage we have is big brains and our ability to regulate temperature. A lot of other animals aren’t really good at regulating temperature as well as humans are. You’ll find extremes where some animals are really good in heat or some animals are really good in cold. But to go from the range of where they can go again that HDR, human dynamic range. Humans are probably the best at that.

The second one would be pH. Our blood has to stay within a very fine level of pH. If it doesn’t, enzyme reactions, a whole bunch of shit hits the fan, so that’s not good. However, you could do some horrible wind gates some 30 seconds all out and repeat that I have high levels of lactic acid in my little air quotes, which is lactate plus literally hydrogen ions, like you’re literally dumping acid into your muscle and into the bloodstream and your body can handle that. Doesn’t feel good, feels absolutely horrible, but you can handle pretty high insults of that. Third would be fuel systems right, everything from fats to carbohydrates in between. And fourth would be just simply air regulation of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

So those would be the four kind of homeostatic regulators and I think if you train within those areas which doesn’t mean that it’s the only thing you’re doing, but if you’re training within those, you’re not looking to change the baseline level. I’m not looking to really alter my pH chronically over time. I’m looking to expand this physiologic headroom Like how low a pH can I go? How high a pH can I go and still be able to function, just like we know people, if you ever do any heat acclimation and we’ve been in Costa Rica before your first day there sucks horribly. You’re like. Two weeks later you’re like, yeah, it sucks, but it’s not quite as bad as it was day one. Right, you acclimate, you get a little bit used to it, your systems upregulate, they’re better able to handle these differences on both sides of the spectrum Totally.

0:30:20 – Speaker 1

Yeah, I just experienced that. I was down in Mexico for two weeks and oh nice. Yeah, the first week. I mean we were there for a fitness and nutrition retreat, so it was workouts and then, oh was that the Don Con. Yeah at Don Con. So yeah so just returned back from that last week. But same thing. Right, I was there two weeks. It was like first week was pretty miserable, You’re just sweating you’re just dying.

I’m lightheaded, I’m feeling when I pass out during the workouts all that stuff just from the heat, when the workouts were fairly intense, but nothing that I wouldn’t be able to get through on a normal day. And then the next week I was like I just it was like flip switch or switch flip. I was like just not sweating as much, not as fatigued, all those different things. And yeah, it’s amazing what the body can acclimate to once you put it under those stressors. So I guess what are you doing for the average human being to try to push this flexibility?

0:31:09 – Speaker 3

That’s a good question. I usually when people hear that their assumption is oh my God, I gotta go buy a sauna or I gotta hang out in cold water immersion for 10 minutes a day and I gotta do all those heinous things. And you flash forward to the video of Laird Hamilton who put the salt bike in a sauna and is in there with oven mitts doing shit. I wanna see his belly button. I don’t think he’s human anyway, but at an extreme end. If you’re, someone like Laird has been doing this shit for many years and that’s part of your life, yeah, you might get there. But the benefit is most people have almost zero adaptation to a lot of this stuff.

Look at temperature. People think I’m bonkers because I live in Minnesota. I’m like, yeah, you live in Arizona, but you run from one air condition thing to the next air condition thing, like you don’t exercise outside, you’re not even ever outside. It’s not that much different than being in Minnesota in the winter. It’s just the opposite direction. And over time, just due to adaptation, you adapt to your environment. For example, in Minnesota, even people who are not outside a lot like it’ll get cold, starting in winter, in November, definitely December, and you’re like oh man, it was so nice with 70 degrees Fahrenheit the other day and it’s 50 degrees today. It’s cold and oh it hit freezing at 32.

This is horrible. But then after you get through winter and spring, like the first spring day it hits 50 degrees. You’re like, ah shit, it’s T-shirt weather. Woo, this is amazing. And these are people who generally are not outside a whole lot either. Yeah, and your body is gonna adapt to that stimulus. So the good part is most people are not adapted to it that much. Therefore, just if you’re new to training, you might be able to curl soup cans and make progress. You don’t need a lot of load, you don’t need to do anything aggressive because your entry level is low and you haven’t done a lot of work for adaptation.

For people with heat a lot of times I tell them like hey, just go exercise outside. If you’re in a warm environment, you don’t need to give yourself heat stroke. Be intelligent about it. It doesn’t need to be crazy, but it may just be. Go outside in the morning where it’s 70, 80 degrees, not at noon where it’s 110. Maybe go for a run, do some kettlebell stuff, whatever. Like, just do something in heat. You don’t need technology per se. Take a cold shower. That can be beneficial on the cold side. Start at 10 seconds. You don’t need to be crazy With like pH stuff.

You can play around with like breathing drills. You don’t even necessarily need to do it during exercise. You could do a Wim Hof like super ventilation method where you’re just breathing really fast or you’re doing a breath hold Again. If you do either one of those techniques, start lying down. Don’t do it anywhere near water. You don’t wanna shallow water block out. You can literally die from that. But if you’re lying down, whereas case you pass out, you’re already on the floor anyway. Like you’re not going to go anywhere, like you will remember how to breathe. So you don’t need to do a lot of stimulation.

Usually I tell people just pick one area that sounds the best to them and then just start there. And once you get pretty good at that, maybe add another area and as you get more experience you can start combining stuff. Maybe if you’re more experienced you’re gonna do a little bit of breath work in the sauna, obviously under controlled conditions, make sure you know what you’re doing, et cetera. So you can stack some of these things together. Or like I’ll take my rower and stick it outside when it’s 90 degrees out and do some pretty horrible intervals and then, once I’m done, I’ll go jump in some cold water immersion for two or three minutes so you can combine some of these things together and the nice part is it’s not really gonna add hours upon hours to your schedule.

0:34:44 – Speaker 1

Yeah, okay, perfect. So and what is exactly, I guess, the purpose for people to do this? It’s just to expand your ability to for discomfort. Is it for health purposes? What exactly is, I guess, the main advantage of pushing that physiological flexibility for people?

0:35:03 – Speaker 3

My biases. I think it’ll just make you more resilient and harder to kill. With more advanced athletes you will see that their recovery seems to get significantly better. They don’t appear as quote in my air quotes fragile. If the temperature is off a little bit, they’re fine. Temperature a little bit cooler, they’re fine. They had to work a little bit harder than what they did the day before, they’re fine. They didn’t have their magical pre 40 grams of carbohydrates, whatever, don’t care, they’re still fine. They’re just more resilient or antifragile to these small little changes that for other people will completely throw them off kilter.

And then, if you go really far down that rabbit hole, like some work we’ve done, is looking at Some of the differences between PTSD or PTG or post traumatic growth. So if you go to the extreme with, for example, like some military groups, where Odds are, you may be experienced to very high level stressors. I Think that if you are better with some of these physiologic flexibility conditions, I Would argue that would bias you more towards post traumatic growth versus PTSD. Now again, I can’t point any study on that per se, but I think it’s gonna bias you to be better able to handle Any other stressors that are coming at you and the stressors still gonna suck, but on the backside you can have more growth from that versus having more negative effects.

0:36:35 – Speaker 1

Yeah, I love that. Yeah, just yeah, the ability to adapt, right like you increasing your adaptability.

0:36:41 – Speaker 3

Yeah, which is awesome to me, makes you more resilient.

0:36:44 – Speaker 1

Yeah, no, 100% right, and even just on the small scale it’s again just came back from Mexico’s. There’s some people that as soon as they hit that heat, it shuts them down. Right, I cannot do this, I’m gonna die. Basically is the way people feel, right? Somebody who’s maybe able to adapt to this stuff a little bit better. It does. I think it just like you said, it just hands with your ability to do things at a higher level and, I guess, deal with that comfort On a higher level as well. I love that idea of the fact that, especially for the athlete or somebody who’s playing like an outdoor sport or something, yeah, a lot of times they see those guys in the NFL and they go down to Florida and half the teams cramping up within the first Whatever quarter of the game and it becomes a real issue. So, yeah, maybe if they do have a little bit more of that physiological flexibility, then you’re just a little bit more Adaptable in that situation and a little bit more available and a little bit more useful. So I love that.

0:37:38 – Speaker 3

Yeah, and one of the things I pulled for the course was I’m like okay, so elite level athletics do a very good job of tracking stuff and there’s also huge money involved. So I look to see that for altitude, for example, is that really an advantage, right? So you have the Denver Broncos who play in Denver, you have Utah Jazz who played a higher elevation and there’s actually some pretty impressive studies and In general I think it was like three studies that looked at this all three of them agree that across different sports At least for altitude right, because your partial pressure of oxygen is going to change the teams who played and practiced at altitude in all cases had an advantage. That wasn’t a massive advantage, but it was enough that it was statistically a big advantage. So there was some very interesting data on that I love it All right.

0:38:32 – Speaker 1

so that’s good, and you brought up a little bit of like hot, cold the breath holding, things like that. Is there any other like main tactics that you’re using to push people’s adaptation to this physiological flexibility?

0:38:45 – Speaker 3

Yeah, with nutrition you go to the next level. Something I’ll do with Advanced athletes is so with most people. I start with what I call a macro matching, meaning if you’re doing primarily a heavy lifting session, we’re going to provide more carbohydrates, so you have plenty of carbohydrates. Your performance is good. If you look at the literature, there’s some very interesting stuff on the. They call sleep low, train high and vice versa, all these different strategies and in general what they find is that if you do a very hard interval session on Lower glycogen, so you’re actually removing some carbohydrates from the system, your performance acutely is not nearly as good. It’s not really a shocker, but your body appears to upregulate kind of these molecular adaptations to a higher degree.

Then if you had carbohydrates present, the model I use is a macro matching For a u stress model. So u stress, e use stress, meaning that you could train on Monday. Tuesday is an easy day in your back. You can train again on Wednesday, so stress you can generally recover from in a shorter period of time. A distress session would be stress that takes you much longer to recover from. So again, using just athletes as an example, if you compete in the CrossFit games and you’ve got three days. You’re just going to get the crap kicked out of you. That’s definitely a distress session, or Olympic weightlifting, me to big game, etc. A lot of times in season athletes are a little bit different, but you have time to recover on the back end and the only thing that really matters on that day is absolute performance on that day. So with a distress model, you can actually have a macro Mismatching where you may do a high intensity session that the fuel is primarily carbohydrates, but you’re going to do various levels of restriction of those carbohydrates Not necessarily for acute performance, which will actually be worse but you want to up regulate some of those adaptations so that when you come back in a couple weeks couple days, whatever and provide the carbohydrates, you hopefully will be at a little bit of a higher baseline than what you were before, because these molecular adaptations will translate into performance. Sounds amazing in theory. The the research on it is Probably about split like 50 down the middle. Marquette did a really great study published in MedSci 2016 that showed massive increases with that kind of approach and these are pretty high level athletes Body comp got better, performance got better. Guild in another study that was similar but not quite the same. Didn’t see those performance increases. So right now it’s mixed again.

My bias is Probably worth doing with advanced athletes in an offseason basis If you think they’re getting close to a plateau. Take a couple weeks, do some method like that. Come back to your normal training. If you increased it, great, you look like a wizard. You’re amazing. If it wasn’t better and it’s offseason, you don’t have a big game. You maybe lost a couple weeks, probably not that huge of a deal.

So there are different ways you can set up trying to maximize these adaptations. So with the physiologic flexibility, what that may look like is simply Doing a longer period of fasting on a day You’re actually going to do weight training. So that would be step one. So, going into it, your liver glycogen is going to be lower, but if you haven’t done a lot of muscular work, muscle glycogen will still be there. You should still be able to perform quite well during that session. If that goes well and you want to take it to the next level now, you might do some horrible stuff like Repeated wind gates or just like these high intensity 30 second out type things. Later in the day Just have some protein, go to bed and then get up the next day and do some heinous like high intensity stuff. So now you’ve depleted liver glycogen, you’ve depleted muscle glycogen, but you’re asking the muscle to do this high output task again. So that’d be some ways of radiating it to a more extreme type of approach. Yeah, that’s cool.

0:42:52 – Speaker 1

I like that idea and, yeah, like you said, if the literature is mixed on that, it would be interesting. But it also does. It makes sense as, like an athlete and someone who’s Push like has pushed themselves to those points right it’s. If you could create some kind of a hyper response. Yeah, that would be incredible. If that was a tool that you used once in a while, then I think that would be super cool. So, yeah, I like that. And then, just for the record, I think, just because I have a lot of people that have a hard time with the protein intake, I don’t think you’re talking about going super low protein, super low protein.

0:43:26 – Speaker 3

No, I’m trying.

0:43:27 – Speaker 1

This is the carbs and fat thing, correct?

0:43:30 – Speaker 3

Yeah, I do have some people when they’re doing a fast like that, they won’t really consume any protein during their fast and the I’ve said I’ve tried both and my initial thought years ago with fasting was oh my god, all your muscles gonna fall off your body. Don’t do this is the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard of my life. And then I started looking at the research to try to disprove that. I was like, oh, there is some interesting research. And then talking to protein researchers like stew phillips and others, if you’re doing some exercise on a completely day where you’re completely fast at no calories, you’re probably neutral towards muscle. You’re probably not losing a ton of muscle for a short period of time. You’re definitely not gaining as much muscle on that day. Let’s say it’s probably neutral ish.

And I played around with like protein only on a certain day and cutting out all carbs and fat and it was very confusing and I just got way hungrier and so did everyone else. Like everyone who did it, it was just Much harder to do it because there was something weird about Once you start eating even if you were just eating protein, you just wanted to eat more. Yeah, yeah, so from a simplistic strategy, again, we’re probably on an extreme case, doing it only like once a week. Most other times you’re having protein every you know, two to four hours. Uh, I did it as a a neutral event, but I do agree. If someone came and said, yeah, I want to absolutely maximize my ability to gain lean body mass muscle as fast as humanly possible without drugs, I would not have them do fasting. All right.

0:45:07 – Speaker 1

Yeah, and that’s. It’s interesting too, because that’s my experience with fasting as well, like I did it for probably Few years at least. And yeah, man, I just found it way. Once you start eating, even if it’s just that you have something small, you have a protein shake. Whatever it might be, it does Spark the appetite.

0:45:25 – Speaker 3

Yes.

0:45:26 – Speaker 1

It does seem to be just a lot easier to hook things from it until you’re you’re given time and then pick it back up. Right, yeah, I have. I have the exact same experience with that as well.

0:45:35 – Speaker 3

Yeah, and your microphone got a little quiet there. Maybe it’s something on my end.

0:45:39 – Speaker 1

Oh, hopefully not, or hopefully everybody heard me but Not all edited out. But all right, mike, and then what one other thing I want to touch on? We got a couple minutes. Can you just explain for people? I think now you’re, in terms of hrv, you’re probably one of the most knowledgeable guys out there on hrv. This is something that’s being provided now to people through apple watches, loop straps or rings.

0:46:05 – Speaker 3

Yep.

0:46:06 – Speaker 1

I don’t think a lot of people know what they’re looking at in terms of numbers right, I don’t think correct and how to interpret the data. Can you just give us a quick breakdown on hrv and how people can use that to their benefit?

0:46:19 – Speaker 3

Sure, with hrv it is like everywhere now, which, again, is a pro ennecon. So far to date I’ve lost like almost every hrv contract I’ve had an initial call with, because it always goes hey, we’ve got this idea for hrv, we’re gonna stuff it in this watch and we’re gonna measure it like every five minutes and tell the user this and that and I’m like that’s a stupid idea, right, because with without context, it’s not gonna mean anything. What if they’re exercising? It says you’re like super sympathetic and stressed out. Yeah, I just did 30 seconds on this stupid ass rower in the middle of my driveway in the heat. Of course I’m gonna be stressed out. That’s actually what I would want to see if I couldn’t increase my heart rate for that event. Something’s wrong. So it’s a good technology and even if it’s accurate, the biggest issue now is that it’s Sexy and people are just putting it in every device and there’s no regard, or the very little regard, for context. So for most people probably 90 percent of people, 90 plus percent of cases Make sure that the system you’re using can accurately measure heart rate variability. The second part is you probably only want to do it once per day, most of the time first thing in the morning if you’re doing a commanded measurement or have it gather, like an oar ring, which I have I’ve got a garment, I use i-thlete, I use different devices have it gather that information when you’re most stable, which is going to be during the course of the night. Now there are some pros and cons about gathering information overnight. For example, the oar rank for hrv is very accurate, but if your sleep is changing a lot, obviously that’s going to impact your heart rate variability. It’s going to impact the data time that you’re gathering it.

For If your high level athlete and you’re resting heart rate at night is 37 beats per minute, your hrv and aura is probably not going to change much. Because of fancy term is what some call parasympathetic saturation. You just have so much parasympathetic tone that these other stressors don’t show up that much. So you may have to do a commanded measurement of some kind First thing in the morning, normally seated or even standing. But for most people aura works pretty good. If you’re resting, heart rate is in the 60s and you’re looking at just general stresses. You’re not trying to really change your training per day, you just want a rough mark or what’s going on.

Hrv through aura can actually be pretty useful. But at the end of the day, hrv will only tell you the status of your autonomic nervous system at the time of the measurement. The autonomic nervous system has the parasympathetic branch, which is rest and digest, like pushing down in the brake of your car, as a sympathetic branch, which is a stress increase in heart rate pushing down in the gas pedal of the car. So when you do a measurement first thing in the morning, it’s giving you an idea of what is the status of your nervous system and I find that super useful because a lot of people are not sure they don’t know if their training did it the next day or they just don’t really know where they’re at and they keep going. If they’re a high level athlete, in general what they do is they push too hard and they fry themselves. General population it’s normally they’re outside stressors that are the main issue that are causing stress to their life, but training is the only thing that can really change. Either way, having an idea of where you’re at becomes useful. The downside of heart rate variability is it won’t tell you what stressor is the main one.

So again, going back to context, I primarily use the IFLEET system instead of athlete, it’s IFLEET. And then you have these little slider switch each morning that you adjust to self-report of how your sleep was, how your energy, how your training, and you can type in a few notes. To me that’s super useful when I look at it from online clients of all types, because now I can see what was your stress level, what’s your resting heart rate and then what is the context. So what pattern keeps showing up again? If their HRV was real low, they’re very stressed and each day of the three days it says their sleep was piss poor. Great, now I know we’re probably going to try to do some intervention with sleep. Or if they say my nutrition was horrible or I just feel really tired, it gives me an idea and a direction to go to try to figure it out, do some type of intervention and then we can look to see, oh, did their stress level get better over time or did it change? So they get some feedback on that system, which I find is super useful.

So even for general population, it’s harder to get them to do an intervention and just be like, oh, just trust me, this will work. They want to see some influence on it. Like, sleep is a good example. They’re like oh, I give up watching Netflix for two hours at night before I go to bed. It’s night three at doing this. I don’t really feel any better. Oh, but look, my heart rate variability is better the last two days. Oh, okay, so it is showing me that I’m less stressed. I don’t quite feel it, but I’ll go with it because I can see a marker of progress that’s actually happening.

0:51:15 – Speaker 1

I love it? Yeah. And in terms of HRV, are you each person will have what’s normal for them, or are we looking for highs and lows?

0:51:25 – Speaker 3

Yeah, Each system will use a different way of doing it. Yeah, so, for example, I think system will measure between one and a hundred. It’ll do the measurement and then it translates it to a one to a hundred scale, just because that’s more meaningful for people. Ordering will do what’s called a time domain analysis and it gives it to you in milliseconds. Other systems may present it a little bit different way, so it’s hard to take one systems reading and transfer to another system.

Also, the position you get the data in seated, standing, lying down as you get it off of what stage of sleep was it an aggregate of sleep? All those things make it hard to compare numbers. And in general, yeah, there’s population data. There’s things of you’re a little bit too low or too high, but most of it is going to be changes relative to your normal.

So what I tell people a lot of times is just get a baseline for two, ideally three weeks, which I know is hard to do because they want to see the measurement and they want to see a change. But just do at least give me two weeks and then we can see where you’re at and then we’re looking for changes up or down. Are you becoming more stressed or are you becoming less stressed off of your baseline, and if you have a very poor HRV, we may then look at three or six months. Over three to six months, was the trend line kind of going up or was it going down, and we can try to make some assessments and changes off of that. Chronically too.

0:52:50 – Speaker 1

Very cool. Yeah, good, that’s a thing I just wanted to cover because I know a lot of people are. The HRV is something that is being provided to them, but they don’t know what they’re looking at in terms of the data. So it gets a little bit jumbled and then, yeah, people are getting really swayed in terms of because that’s the thing that gets me about. That is, I know, like you’re a big data guy, you’re measuring everything, like you got the metabolic heart sitting in the jar. But I hate because, again, like I’ve had whoops, I’ve had auras, I’ve had whatever you name it, and maybe, if this is just stubbornness or stupidity on my end, but I hate letting something like that get determined my output for the day.

So I felt a weird correlation between when my whoops strap said my recovery was shit. I felt amazing on those days when my strap said my recovery was great. Those were some of my worst days energy wise, and so I got to the point where I was like, well, if I’m going to follow this thing, every time it tells me I need to take a rest, I don’t know if this is the best thing for me, just based off of my own personal feeling. Right Like a tricky thing in a slippery slope. Now, for somebody like you who’s literally researched this for half of their life, I think obviously you’re a professional at this.

When you’re putting this stuff into the hands of your average Joe who wakes up in the morning, drinks too much coffee, goes to work, sits for 10 hours, might get a workout and watch it too much TV at night, like you said, is this a necessary? Is this something that where, when you wake up in the morning and your aura ring says that your recovery is low? Is that something where you go, oh, I can’t train today, I can’t take today off, and that’s the only thing that gets me is? It’s like when we’re talking high level athletes and people who know 100% how to interpret the data. It’s one thing right, but I think it’s again. Sometimes you get that paralysis by analysis If you’re just trying to hang on all these different whatever technologies and stuff before you take care of, like the lifestyle.

0:54:46 – Speaker 3

Yeah, no, I actually agree with that. Like when I started using hard rate, variability got by 10 plus years ago. I was looking at in the lab, starting 15 years ago. I just applied it to my general clients general population clients because I just wanted more data and my hypothesis at that point was exactly what you said it’s not going to be useful, bro. You just need to go to the gym and do some lifting for crying out loud or have a chicken breast. Go do something, right, which is true. But I wanted more data just to see what was going on.

And what I realized with the general population was I had more leverage to get them to do the other things that I wanted them to do because of the awareness, right, and I may not, in those cases, change their training. I may be like, okay, let’s try to have you actually eat like some whole foods instead of cheese doodles before you go to the gym, right? Oh, wow, my HIV was better. My performance in the gym didn’t feel so hard. Cool, let’s have you try to make your bedroom darker at night. Turn a fan on so you have white noise, like I would try to do these other lifestyle interventions and then they would see their stress wasn’t as bad. So, okay, cool, training a lot of times, unless I had to, would be the thing I wouldn’t change. Now again, the caveat is you will run into some clients where they’re like bro, I don’t tell you, I don’t care what I like my cheese doodles. Fans are stupid. Trying to get them to do any lifestyle change is almost impossible. So with that case I would be like, okay, let’s have you still go to the gym, but let’s just do half the volume you did before, right? So I, unfortunately, would cave and modify some of their training more or less, because I didn’t want them to, long term, just burn out and get completely frustrated with the whole thing and just fucking all screwed, throw the towel in that type of thing.

And then for a higher level athletes it’s almost the inverse. Like I’m using HRV to have them, bro, just stop training today, you can do a rest day on Sunday. Like all your gains won’t disappear. I promise you you’ll be fine. And in your case, like, assuming HRV is accurate, you are corrected for acute level performance. Generally, if you are more stressed or are a little bit more on the sympathetic side, your performance in that session is normally better, which makes sense, right. You are a little bit more stressed, so your output in that session can be better. If you get really too high parasympathetic, your performance is dog shit, it’s bad. However, if you get a little bit parasympathetic, that’s the happy medium range.

Quick story I did something really stupid when I was doing heart rate variability. I thought that the more parasympathetic you were, the more recovered you were, and so I started watching this each day. I started doing training for a strongman competition and I didn’t have any implements. I wasn’t able to get to a gym. It’s the middle winter, I’m training in my garage. So I said, okay, 225 on a trap bar for sets of 25 will simulate some of my medley training as best I could. So I started doing that for multiple sets.

It was just freaking horrible doing four sets of that. I wanted to carve my right eyeball out at the end of the day. But I would look at my HIV the next day and I’m like, holy shit, my HIV went up by like 12 points. That’s crazy. And then I would do it again the following week. And then I was an idiot and I started doing it twice a week and HIV kept going up. But then, four weeks into this little experiment, I felt like I got hit by a truck. I’m like dude. I’ve been sleeping 11 hours a night. I’ve been eating everything in sight. I feel like crap. All my other lifts are dog shit. I’m like this HIV is like the stupidest thing, like why am I studying this stuff? And when I looked at the trend over those four weeks it was straight down, but acutely. The next day it would go up, but 36 to 40 hours later it would drop well below baseline.

So, the mistake I made was putting too much emphasis on each individual day, not looking at the overall trend of what was actually going on. So that’s why I’m not a huge fan of looking only at the aggregate score, because it can bleed you down some bad paths at times.

0:58:55 – Speaker 1

I love that. No good man. I’m glad I brought that up then because that’s super helpful. That’s good to know and also, too, I like that. Look more to the lifestyle adjustments that can be made, as opposed to every day you need a rest day, kind of thing. It’s now you need an adjustment here.

0:59:13 – Speaker 3

And there are times where, if it’s a high level athlete and they’re red and their average is good, I’ll be like, yeah, go to the gym and see if you can set a PR and I’ll cut your volume in about a third of what it normally is. And they’re like what? You’re an idiot, my HRV is red. I’m like just trust me, because I know they’re very sympathetic. And when they do it they’re like yeah, I got a PR, I got really close, perfect, so I’d add another rest day the day after and we continue on with their training cycle. The reason for that is they were very sympathetic, their average was okay, so I know they can handle a little bit more acute stress.

And then if they happen to show up red, like the day before a competition which most of time they do I’m like hey, remember that last time, eight weeks ago, we did this, or HRV was red. What happened? Oh, I went to the gym and hit a PR. Yeah, exactly, you’ll be fine, don’t worry about it, because at the back end of the competition, most of the time you can take multiple days off, so I’m not worried about accumulated fatigue at that point. I’ve done the experiment. They’ve already shown themselves that this is not going to impair my performance, if anything else that may help my performance. So that kind of gets rid of that sort of negative potential mental aspect out of it too.

1:00:21 – Speaker 1

Totally no. That’s amazing and, yeah, it makes perfect sense, right that more sympathetic you are, the better the performance is going to be.

1:00:26 – Speaker 3

Especially for speed and power, like strength type based sports. Yeah.

1:00:29 – Speaker 1

Totally amazing, awesome. I’m glad we covered this then.

1:00:33 – Speaker 3

So yeah.

1:00:34 – Speaker 1

I could talk to you off all day, but I’m going to let you get on with it. Today We’ve got 40,000 other things on the go right now. We’ve got the folks to go right or kite, board surf or something like that.

1:00:46 – Speaker 3

Yeah, a couple things.

1:00:49 – Speaker 1

Awesome. I appreciate you being on man. You are an absolute wealth and all. It’s been a pleasure to have you on the podcast today. Oh, where should everybody find your info?

1:00:57 – Speaker 3

My best place is. The main website is miketeenelsoncom, so you’ll be able to get on in the newsletter. Most of the information I have right now goes out over the newsletter, so there’ll be some opt-ins you can get in there on the newsletter. Tell me you’ve heard me on this podcast. Some email reply and I’ll tend to a cool free gift. Also have a podcast which you’ve been a guest on which is awesome. That’s the flex diet podcast. And then Instagram is Dr Mike Teenelson.

1:01:24 – Speaker 1

Perfect, all right, everybody, if you haven’t already, go look Mike up, because it’s nothing but good factual information on there and obviously everything you just hold up today was incredible. Thanks a lot for being on, mike, and we’ll definitely see you around.

1:01:37 – Speaker 3

Yeah, thank you so much. Great, I appreciate it. Awesome, you got it.

1:01:43 – Speaker 2

Please note that this podcast is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. The information shared on this podcast is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be used as a replacement for the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider. Additionally, the opinions and strategies discussed on this podcast are those of the guests and host and do not necessarily represent the views or endorsement of the podcast or its creators. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Transcribed by https://podium.page

Leave A Comment