Regardless of how hard-core you are, there will be times throughout the year when you take a break from your traditional training. Whether a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic deadbolts the doors or you take off to the beach for an epic kiteboarding vacation, almost everyone steps away occasionally. Good news. I have the S4 Model for Returning to the Gym

Once again, I had a blast working and kiteboarding in South Padre, TX this Spring. My wonderful wifey Jodie got up on the board and rode both directions for over 15 seconds each direction on two different occasions, which is a huge milestone!

I had some epic PRs of over 4 hour session, 60 + miles at once, max 12.6 feet of air and 6.1 seconds of hang time.

During the trip, my main fitness goal was kiteboarding so lifting took a backseat (check here for my top 5 fitness learned kiteboarding).

Once I got back home, those goals flip flopped as it is easier to lift here since the wind is a bit iffy most days.

While in TX I was still lifting, but it was more upper body focused as my lower body, hamstrings and quads were quite sore a vast majority of the time. I did my AM aerobic running 5 days a week, which was enough to keep my aerobic adaptations steady.

Lower body lifting was a rude awakening once I was home though.

Squats felt super hard, and deadlifts were only marginally better.

The good part is that I have done this before and also used this approach coaching my online M3 1-1 clients these kinds of transitions. No worries when we have to change up their training.

S4 Model for Returning to the Gym

1) State

Once you are back home it can be easy to take several days or weeks in some cases to get back to the gym. You know it is going to suck so you avoid it.

The first step is to make sure your state/ mood is good; then go lift.

This can be tricky as you will want to project crappy states into the future. Common things I hear are:

“This will suck since I have not lifted in 7 days.”

“Ugh, I wish I did something other than 12 oz curls while I was on vacation.”

“I will go tomorrow.”

Start sooner than later. Get yourself in a state/ mood, then go to the gym.

2) Specific

The fastest way back to your goals is to work on them specifically.

I know, I know . . . sounds way too simple. Part of my “job” here is to not always tell you new stuff, but to remind you of things you already know.

If you want to deadlift more weight, you need to deadlift.

You want to row a 7 minute 2K on the Concept 2, you need to get said glute max on the rower.

You get the idea.

Set up your training with the specific items you want to improve sooner than later.

What I have seen in those not working with a coach is that they put those exercises off for awhile . . . They don’t want to face the music of taking time off.

Get back on the horse.

3) Stress

Now that you are doing the specifics that you want to improve, work on them via a point of better leverage.

What?

Let’s take the deadlift as an example. We will assume your goal is to trap bar deadlift 405 x1 from the floor with standard handle height.

You are already working on it from the floor (specific) and now add in some work from a higher leverage point – which here would be raising up the handles via larger plates (aka wagon wheels), setting it up in a rack (aka rack pulls) or placing something under the weights to raise them up (3/4 in rubber farm stall matts cut into smaller squares and stacked works great).

This allows you to lift a heavier load since the range of motion is less and your biomechanical leverage is better.

An interesting thing that I have noticed from taking planned periods of time off is that your sensation of what is heavy changes quite quickly.

My first trap bar deadlift after not having lifted anything over 225 lbs in 7.5 weeks was a high pick point (leveraged) with wagon wheels at 315 for only 5 reps. Previous it was easily around 405 for 5 on a bad day.

My hypothesis is that my physical tissue is different post time away from heavy lifting; and thus, the sensation is that a lighter load feels heavier. It is your body’s way of protecting itself.

A very cool study from Dr Luc vanLoon’s lab looked at this recently and found that soft tissue (they looked at tissue from knee operations in humans) changed at about the same rate as muscle!

Say what?

Yep, soft tissue and muscle appear to upreg and downreg around the same rate . . .

“With fractional synthetic rates averaging 007 +,- 0.02 and 0.04 +,- 0.01 % per hour for anterior and poster cruciate ligaments, respectively, we observed that both turn over at a similar rate compared to skeletal muscle tissue” (1).

In English, Dr Nerd, please. Your soft tissue and muscle are bit less adapted to heavy loads as they changed their structure in the absence of heavier loads.

Now, this will come back, and it would be wise to listen to your sensations of what is currently heavy. Do NOT jump right back to your previous best after some time away.

4) Spike

Another potential for injury is a large spike in training volume. This is based on the work of Dr Tim Gabbett and others (2-9).

Most of the time, slow and steady increase in load over the course of a training cycle keeps this in check.

HOWEVER, you can run into issues when you have an extended time off, and then you go from zero / very little load to a big jump in loading. Percentage-wise, this can be a massive load spike. My bias is that this is related to point #3 above – Your tissue is just not quite ready for it.

Summary:

Taking time away can be great for both physical and mental reasons; no need to fear it. Use the S4 Model for returning to the gym to slowly work your way back and reduce your injury risk at the same time.

Cheering for your greatness,

Dr Mike

PS – if you want to learn about all the principles that I use to train clients online in addition to business /marketing, mindset and much more, check out the Flex Diet Certification course.

References: (nerd fuel)

1. Smeets JSJ, Horstman AMH, Vles GF, Emans PJ, Goessens JPB, Gijsen AP, et al. Protein synthesis rates of muscle, tendon, ligament, cartilage, and bone tissue in vivo in humans. PloS one. 2019;14(11):e0224745.

2. Malone S, Owen A, Newton M, Mendes B, Collins KD, Gabbett TJ. The acute:chonic workload ratio in relation to injury risk in professional soccer. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2017;20(6):561-5.

3. Gabbett TJ. Debunking the myths about training load, injury and performance: empirical evidence, hot topics and recommendations for practitioners. British journal of sports medicine. 2020;54(1):58-66.

4. Gabbett TJ. How Much? How Fast? How Soon? Three Simple Concepts for Progressing Training Loads to Minimize Injury Risk and Enhance Performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(10):570-3.

5. Timoteo TF, Debien PB, Miloski B, Werneck FZ, Gabbett T, Bara Filho MG. Influence of Workload and Recovery on Injuries in Elite Male Volleyball Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(3):791-6.

6. Andrade R, Wik EH, Rebelo-Marques A, Blanch P, Whiteley R, Espregueira-Mendes J, et al. Is the Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) Associated with Risk of Time-Loss Injury in Professional Team Sports? A Systematic Review of Methodology, Variables and Injury Risk in Practical Situations. Sports Med. 2020;50(9):1613-35.

7. Szigeti G, Schuth G, Revisnyei P, Pasic A, Szilas A, Gabbett T, et al. Quantification of Training Load Relative to Match Load of Youth National Team Soccer Players. Sports health. 2021:19417381211004902.

8. Debien PB, Miloski B, Werneck FZ, Timoteo TF, Ferezin C, Filho MGB, et al. Training Load and Recovery During a Pre-Olympic Season in Professional Rhythmic Gymnasts. Journal of athletic training. 2020;55(9):977-83.

9. Gabbett TJ, Whiteley R. Two Training-Load Paradoxes: Can We Work Harder and Smarter, Can Physical Preparation and Medical Be Teammates? Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12(Suppl 2):S250-S4.

Rock on!

Dr. Mike T Nelson

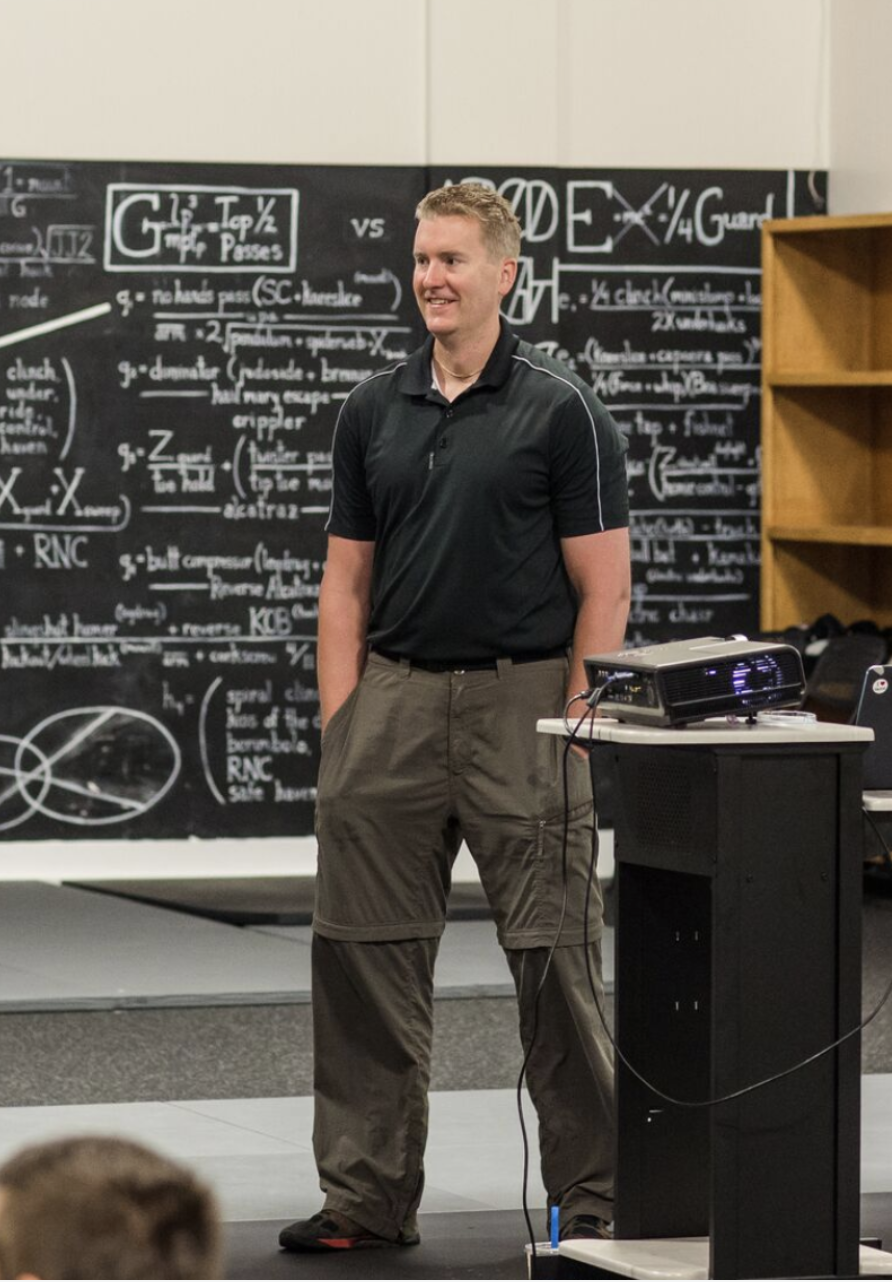

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Leave A Comment