Today I’m talking to Professor Lauri Nemetz, author of the newly-released book “The Myofascial System in Form and Movement.” If you’ve ever wondered how the myofascial system can affect movement pain, or you’re just a big anatomy geek like me, you’ll love this conversation.

Today’s episode is brought to you by miketnelson.com. Sign up for my fitness insider newsletter for daily training, nutrition, and sports performance tips.

Listen to hear:

-

[4:34] Working in a cadaver lab and unexpected findings

- [18:40] Asymmetry in the body and in professional athletes

- [24:19] How we shape what’s around us and what’s around us shapes us

- [32:10] Curiosity in life and movement

- [40:37] The importance of making mistakes

- [48:18] Flexion and extension

- [52:39] Defining fascia

- [56:48] Why fascia has been ignored

- [1:06:21] Teaching origin and insertion

- [1:22:52] Can fascia be changed structurally?

- [1:30:31 Hands-on fascia work

- [1:33:42] Can fascia hold emotions and memory?

Lauri’s book:

The Myofascial System in Form and Movement

Valid for a 30% discount off a copy of The Myofascial System in Form and Movement for individuals located in US or CAN when pre-ordered through us.singingdragon.com.

Use code: FORM30

Connect with Lauri:

Additional Resources:

Static Stretching is Dumb – Dr Mike T Nelson

Anatomy Trains Course Moving Through Trauma – Dr Mike T Nelson

Training the Core for Strength Sports – Guest Podcast

Dr Mike T Nelson Fresh Tissue Dissection Notes

About Lauri:

Lauri is an Adjunct Professor at Pace University (NY), Visiting Associate Professor Dept. of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Rush University Medical Center (Chicago), a licensed Creative Arts Therapist, a member of the American Association for Anatomy, a board-certified member of the Academy of Dance/Movement Therapists, a Yoga Alliance yoga teacher and education provider at the 500-hour level, a Stott Pilates instructor, certified yoga therapist (IAYT) and provider and former faculty for Anatomy Trains ® and Anatomy Trains ® Dissections.

She co-leads www.knmlabs.com and guests internationally for dissection projects including the Fascia Net Plastination Project. She is the author of The Myofascial System in Form and Movement (Handspring Publishing, Dec. 2022) and a contributor to The Anatomy of Yoga Coloring Book (Staugaard-Jones and Nemetz, North Atlantic books, 2022) as well as numerous articles. She has presented internationally including at Harvard Medical, Oxford University and at conferences for the American Association for Anatomy and more. Information available on www.wellnessbridge.com.

Rock on!

Dr. Mike T Nelson

Dr. Mike T Nelson

PhD, MSME, CISSN, CSCS Carrick Institute Adjunct Professor Dr. Mike T. Nelson has spent 18 years of his life learning how the human body works, specifically focusing on how to properly condition it to burn fat and become stronger, more flexible, and healthier. He’s has a PhD in Exercise Physiology, a BA in Natural Science, and an MS in Biomechanics. He’s an adjunct professor and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s been called in to share his techniques with top government agencies. The techniques he’s developed and the results Mike gets for his clients have been featured in international magazines, in scientific publications, and on websites across the globe.

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- BA in Natural Science

- MS in Biomechanics

- Adjunct Professor in Human

- Performance for Carrick Institute for Functional Neurology

- Adjunct Professor and Member of American College of Sports Medicine

- Instructor at Broadview University

- Professional Nutritional

- Member of the American Society for Nutrition

- Professional Sports Nutrition

- Member of the International Society for Sports Nutrition

- Professional NSCA Member

Welcome back to the Flex Diet Podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Mike T. Nelson. And today I’ve got a very fun and wide-ranging discussion with my friend, Lauri Nemetz all about the fascial system. If you’ve ever wondered about how this can affect potentially movement pain, and you’re just a big anatomy geek like myself.

I think you will really enjoy our conversation here. And the podcast today is brought to you by myself as usual. And go to miketnelson.com. And there you can get on to the newsletter. That’s where probably 90% of my content goes out. And there’ll be different opt-ins you can use there. We can give you some fun gifts, such as a report on magnesium or even protein.

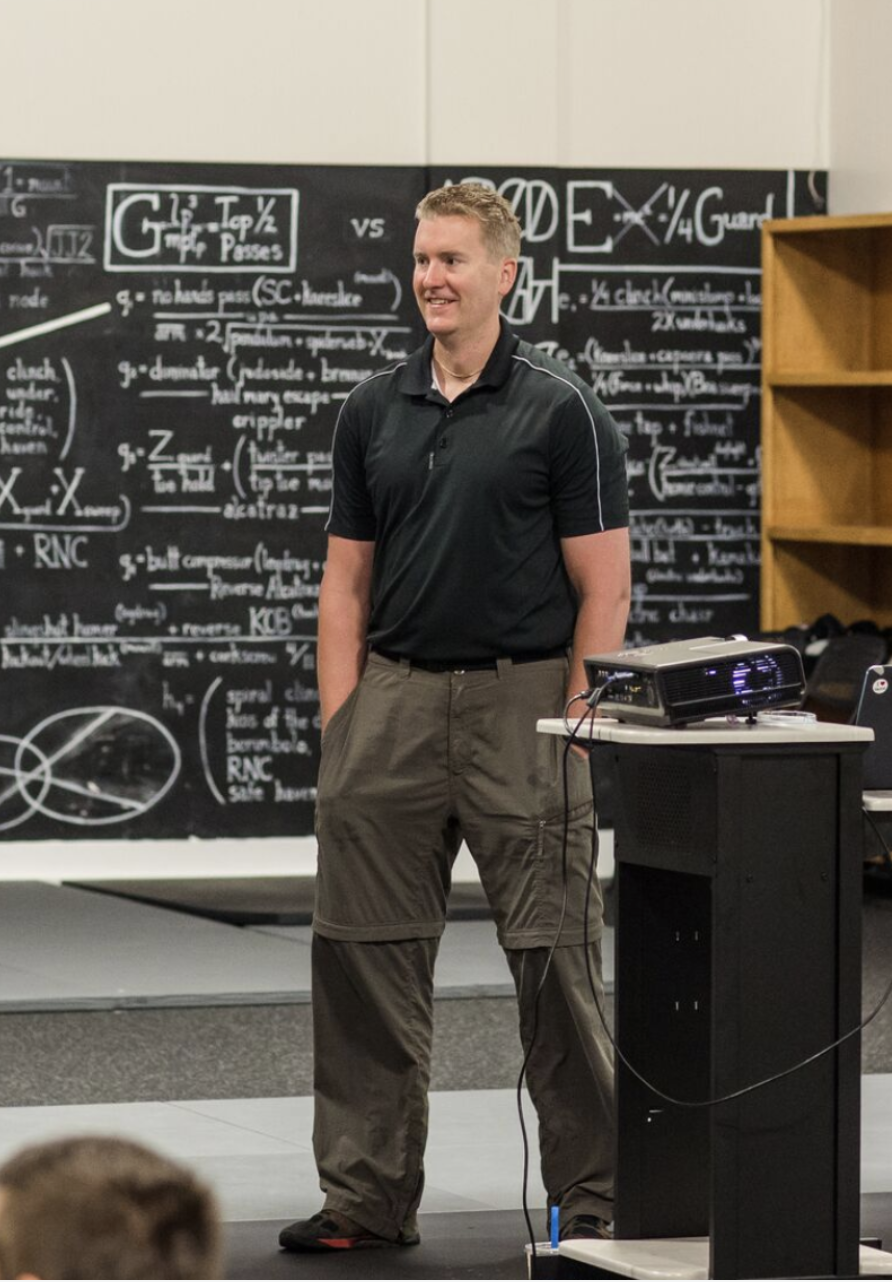

So go to miketnelson.com. And enroll in the free newsletter for all the latest information. Like I said, that’s where the vast majority of my content goes out. Sometimes I republished it on social media. And then a lot of times I don’t. So if you want exclusive content go there. And then today in the podcast, as I said, my friend Lauri is here. She’s an adjunct professor at pace university in New York.

And she’s also an associate professor at the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation at rush university medical center in Chicago. She has a really wide background. Everything from a yoga to dance therapy to much, much more. I originally met her several years ago at a fresh tissue dissection course.

I did with Tom Myers. You’ve probably heard of him in regard to the fascial different systems. And the head dissector there was Todd Garcia. So I got to spend a week working on fresh tissue cadaver. And I’ve done this three times now. And Lori has been one of the great TA’s every time. So it was awesome to get her on the podcast here. And she also has a brand new book that is coming out.

Called the Myofascial System in Form and Movement. So we will definitely have a link to it. It just came out. So I haven’t had the ability to look at it yet, but I’m sure it’s going to be amazing and super interesting. So enjoy this conversation with Lauri Nemitz.

[00:02:41] Dr Mike T Nelson: Hey, welcome back to the Flex Diet Podcast, and I’m here today with very special guest, Lori, who’s gonna introduce us and talk to us all about

[00:02:51] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: fascia. Excellent. Yeah. Happy to be with you. Happy to see

[00:02:55] Dr Mike T Nelson: you again. Yeah. Thank you so much. And I know we first initially met at one of the Tom Myers cadaver dissections.

God, what was the first time? Was it eight years ago now? Longer than that. .

[00:03:08] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: I started back assisting I think about a decade ago. And yeah, I think it was about eight years ago was the first time I saw you in one of those labs, so that was great.

[00:03:18] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. And how did you, for people listening, doing work on cadavers and then it’s also fresh tissue?

So for the listeners, most of the work, like when I did my undergrad, we are lucky to get new cadavers every quarter, which for an undergrad program that anyone could enroll in was extremely rare. But they were all what they call fixed tissue, right? So people have heard of embalming fluid or formula or formaldehyde or whatever words get associated with it.

And it was nice because everything stayed in place and it stops all the proteins in space. But when I got to do some work with you and with Tom, was really the first time I did anything with fresh tissue. So it still has, all the blood and everything in it. And for me, the biggest difference was just the clarity.

Because when you do fixed tissue, everything just looks the same color. Yeah, you can see muscle structures and stuff. I think you lose a lot of the detail and realize how much fat is everywhere. Obviously blood is everywhere. , texture of the tissue, how fragile a lot of the tissues actually are.

So just, I’m curious how you got into assisting and helping with working in a cadaver lab.

[00:04:29] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Ah, yeah, there’s a lot.

[00:04:30] Dr Mike T Nelson: There’s a lot. I know there’s a lot. I just kinda ram for a little too long. ,

[00:04:34] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Uninvolved. We’ll get into it all and fixed versus unfixed tissue and definitely gives a different feel and a different look for people.

What you and what you hinted to for your listeners is that most of what we see in our modern anatomy books is that fixed tissue, and that’s what turns people off. It’s that grain un unpleasant look to the tissue. And when we work with almed tissue, it is definitely much more quote unquote lifelike.

But the advantage it has too is that the body is still quite. It’s a thing that people think, okay, bodies, once they’re dead, become stiff and then they’re immovable and immobile and all of these things. But that’s only a very temporary thing right after death after that initial period.

Actually the body is quite mobile and we can see that in unfixed tissue. And there’s advantages, as you said, to both if you are working fixed tissue and you’re working in, a medical class and you have to have your same, cadaver form for the whole semester. There’s a big advantage to having bacteria, being able to be starved away and all of those sorts of things.

But the big disadvantage is we lose some of what we can see, particularly things like fashion. Yeah. Gosh, , how did I get into all of this? This is an interesting question too. I’ll touch upon that and then we’ll get into even more with cadaver labs, cuz I’ve been in many different areas.

. But I think, you know too I go back to, I had been a teacher with Tom Myers as senior faculty for about 10 years. Most of the time also in cadaver lab. I’d actually started off first in Gil Headley’s lab, a number of before that the Fuzz guys, some people don’t know, but I’ve been through all different old school types of labs and all.

And actually there was Tom’s recommendation to go explore with Gil and I also had seen, Antonio STK early on. Nice. In New York City. I had gone to Mount Sinai, it was called Mount Sinai at the time in New York City, two for a functional anatomy workshop. I’d been to a couple other things.

Too many of those, initially some of what Gil was working with, Fixed tissue. But anytime, the trend started to reverse especially in all the labs that people were interested in. Fascia for that very recent, cuz you can see it a lot differently. And interestingly enough, I worked on the Freya project, the PLA nation project that was done with body worlds and that was to show and highlight fascial tissue.

But because of the nature of how we have to do the pla nation process, that was back to being fixed tissue. So it’s an interesting thing of how you unwind what or don’t see at any given time. And this has fascinated me as far as history. In fact, in a few days I’m getting on a plane to go over to Italy partly to be on a trip to look at art and anatomy.

Partly research for another project ahead. Little hint about that as well. But because I’m really fascinated at what different points in history, did we see certain tissues and what points did we not, because words matter. Images matter, , all these things matter. As in movement and all too, what we don’t know or get exposed to goes away.

So we want to be very rich in our ability to see the body in all of its glory in different forms. And in the same way too, as far as movement, we wanna, have that richness in the body too. If you only look at embalmed tissue, you think the body only works a certain way, , or likewise, if you only work with, different things at different points.

So that becomes an important thing that can inform how we then educate ourselves or move, or what insights we have into things. So I find that all really fascinating.

[00:08:44] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. Lots of stuff there. And for listeners who are probably referring back and yelling at their podcast player now about rigor mortis and crime show investigations and whatever, it’s for a short period of time.

So ATP is used to reset the actin and mycin connection. So actin and myosin of the little contractile things in the fibers. When at t p, the cellular currency kind of resets those heads so that it can fire again. So if you die, you don’t have any creation of a t p. These actin in myosin heads get stuck together for a period of time, which is called rigor mortis.

But that’s a, on the timeframe, that’s a relatively short thing. So we’re talking about after that point where that’s no longer a factor. The bodies are actually quite mobile then at that

[00:09:36] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: point. Exactly. Exactly. And the interesting anything thing, as you’ve seen too in lab, not only do they become more mobile, but even as we dissect, there’s certain layers, the tissue holds a little bit tighter than other layers.

Just by nature of, again, being relaxed, it’s almost like being under anesthesia. There’s a lot of nervous system patterns that get held in the body that, if you saw, again, elderly client, but who’s under anesthesia, shoulder may be wildly, much more mobile than it is in life. There’s some protection in that as well for people to guard against injury.

But sometimes it becomes a habit that’s too strong. So not only have we let go of rigor mortis, but we also see an unwinding probably that takes us back several years from when this particular body, had passed into, again, more free movement and form. Because oftentimes as you see too, beginning of a lab, we’re looking at, okay, what was range of motion?

Where are there restrictions? Where do we think there were surgeries? What is this all about as well? And what are we gonna unwind when we get under that surface?

[00:10:53] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. You mentioned range of motion and anesthesia. Years ago there was a rumor which maybe is still going around it, it seems to me that like fitness and everything related that you have to be in one camp or the other, or you’re not with the cool people.

So you’re either keto or you’re for carbs or against carbs or high protein, low protein. And in the movement world, it seems like you’ve got the very heavy biomechanical centered thing where it’s only the tissue that matters. And then you’ve got the other range, which is the tissue doesn’t do anything without the neurology and it’s neurology.

That’s the super important. And my buddy Adam Klok teaches that it’s the neuro biomechanical model that it’s, yeah, that’s great. It’s both of the things like, you can’t say it’s a hundred percent nervous system. You can’t say it’s a hundred percent just tissue. And so one of the rumors was that someone under anesthesia would have.

Complete range of motion and everybody can do the splits, but my under understanding is that’s no, that’s not quite fair. Not entirely true either. Yep. Like you get more range of motion, but it, you get more, it doesn’t magically fix

[00:11:57] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: everything. . Yeah, exactly. It’s not gonna take away everything. And I’m right there with you.

It’s it’s a com combination of different things and we can hold two different thoughts at once. We don’t have to, again, go to one thing or the other, but Yeah, I’m right there with you. It doesn’t magically mean full range of ocean for everybody by any

[00:12:17] Dr Mike T Nelson: means. Yeah. Yeah. Cuz that’s what amazed me.

Like you, so the thing that still boggles my mind is I’ve probably told the story before, one of the first times we did the class, we get the body, we’re doing our range of motion testing because, at that time, I think it was one of the early classes, we didn’t have any history on ’em.

We don’t know where these people came from. , we don’t know anything about ’em. So we’re, writing on the board and doing our range of motion tests and the cadaver, we had her right knee. Like I went to bend it, I maybe got 10 degrees. Yeah. And it felt like a very hard stop. And I’m like, okay, so right down range of motion.

And so we get that done and the first step is we start removing some of the skin. So I’m working on the right knee, get most of the skin moved around the knee and I’m like I should be a good little scientist. I’ll do my little range of motion tests. And I, in my head I’m like thinking, ah, I’m just going through the, to make sure I did all the steps.

The knee’s not gonna. And her ego is like almost well past 90 degrees. Yeah. And I’m like, oh shit. My first thought was, what did I cut, what did I screw up? ? It was like the first day I’ve already hosed up the cadaver and I’m looking and I’m like, God, I don’t think I, I see anything. And so I called the main guy was running the lab over Todd.

. And I asked him, I said, Hey man, here’s what I did. And he looks at me and he goes, yeah, that happens. And he just walks away. Yeah. To him he sees this stuff like all, and if you’ve met him, this makes perfect sense. Like it very straight matter of fact, like super good at what he does, but to him was like, no big deal.

It’s yeah. And so I like, I grabbed to, and I said, Hey, what the hell’s going on with this? And he is we think that maybe there’s some restrictions related to how the layer of the skin is interacting, with the rest of the enemy. And at the time I’m still thinking, I don’t know, there’s something in the knee, there’s some particle floating around that just moved or got dislodged or whatever.

And a couple days later we get to, take the entire knee apart. And it was an older lady, I think in her nineties. The knee looked like perfect it there, you could not, I’m not an orthopedic, but you could not find anything wrong with the knee internally. And that always again, it’s the net of one experiment, et cetera, that it always just stayed with me of the stuff you think, and then you see something like that and you’re.

I guess we, the skin isn’t super pliable. We have to have some movement within this, ack of skins. It makes sense. So back to your model about the kind of the neuro biomechanics of stuff too. And you don’t always find what you would expect to find either.

[00:14:41] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Exactly. And we’re, I think those of us who really are so interested in seeing more, we, people are amazed. I’ve worked now on hundreds and hundreds of cadavers and there’s always something that’s different I haven’t seen before, but we know this in our living friends and colleagues and clients and everything else.

There’s a lot that goes by the numbers in the book. And then there’s a lot that, people are creative, nature’s creative, biology’s creative, and sometimes we find something we’ve never seen before. Or an un unexplained reason for a restriction that we don’t fully have. We can’t say for sure.

And I think in some ways, the more you get into this sort of work , if you’re any good at it, you get more humble and you get more into going, okay, I don’t know, but here’s, again, some guesses in, in what we do. I do that in the movement work I do with people too. Or as a professor at the university.

I’m think of myself more as a trail guide than absolute whatever. I’ve hiked a lot of metaphorical pathways. . I can guide somebody, but they’ve gotta do the work and. , there’s always unexpected weather , so to speak, in anything that we do. So it’s really interesting. Keeps it

[00:16:02] Dr Mike T Nelson: fresh.

Yeah. And I think that’s the hard part looking in. At least I’ve had more of an appreciation of the variability between one person too than next. Yeah. And you can look in the literature, right? You can find crazy stuff like, Dexter cardia where your heart is literally like completely reversed. And in a previous life I worked for a medical device company, so I got to intend some implants of our devices. We’re putting in pacemakers, defibrillators, and I was just observing. I’m standing behind the anesthesiologist and they make a little incision up by the clavicle, up by your collarbone, and they stick a wire in that goes down basically the venous side of the right side of the heart so they can put the lead, the little wires in there.

Okay. And we’ve, I’ve seen this like hundreds of times and so I’m sitting there watching and all of a sudden I see the wire go all the way out and then straight down into what appears to be the lung, right? Because you’re looking on fluoro, fluoros, just a 2D image and everyone in the room just stops.

You could hear like a pin drop. And I’m standing behind the anesthesiologist and I’m looking at the patient’s monitors expecting them to crash and I’m gonna, get the hell outta the room cuz the shit’s gonna hit the fan and the vitals and everything were fine. Yeah. What the, and the physician looks and you can see him puzzling for a sec.

Looking at the monitor, you see him moving the wiring. And they realize that the patient has, it’s called the persistent left main. They have a weird anomaly in their vessel structure where the vessel’s in kind of the wrong spot. And so it’s a 2D image. So it was going, basically what looked like through the lung, but it wasn’t going through the lung.

It was still in the vessel. It was going yeah. But that was freaky. I’m like, oh my, and I asked the anesthesia, I’m like, what the hell is that? And he is oh, here’s what it is. I’m like, oh my God, I’ve never heard of that before. And Noah knew ahead of time you there was no indication the patient wasn’t symptomatic because of that.

They were symptomatic for a different reason. So to me it’s always fascinating how similar humans are, but yet different. And when you’re working with someone in person, like you don’t have imaging, like you don’t have anything most of the time. So you don’t know what the exact structure of their hip, but they’ve got some weird thing in their shoulder or whatever.

Like you said you’re trying to figure it out as you go. And it may be that they’ve, at the end of the day you’ve tried a whole bunch of stuff. Maybe they just have some weird structure and that doesn’t necessarily work for ’em. But I think especially in fitness, you’re taught always squat with your feet, going this direction, oh my God, your right foot can’t be a little bit more externally rotated than your left.

And everything has to be like perfectly symmetrical. And at least to me, it just seems like the more work I do, the more you realize how much everything is. It’s always slightly asymmetrical and sometimes massively asymmetric.

[00:18:44] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Some of our elite athletes too are massively asymmetrical. Yeah, hundred percent.

Cause of, to their advantage of the sports that they participate in. But sometimes, you look at, you mean some of our elite runners, they don’t have the ideal gate pattern and somehow, they make it work. So again, we have to sometimes reframe what we think and how we apply that.

Because people are endlessly, like I said, creative to solving problems. So what is, the best efficiency for this particular body and it may not look like, what we see for somebody else. So we have to keep that in mind. And you also brought up a really good point too how we see things again, so matters.

If you’re looking at 2D imaging, and thank goodness there are people who can read these things really well and look at that, but when you’re in cadaver lab, you see a three dimensionality that very few people have that privilege to take a look at, and you start to be able to problem solve a lot better because you think now in a little bit more of a three-dimensional way.

Because our atlass are still relatively flat. We do have some of this holo holography and everything else, and 3D imaging, but it’s a very limited number of specimens at this point. So to be able to actually go into a body and to be able to explore that is really, exploring terrain in a very unusual way, but very profound way

[00:20:18] Dr Mike T Nelson: as well.

Yeah, one of my favorite sayings, and I don’t know who said it, is that the map is not the terrain, right? The map is a represe representation, or room map is not the territory, right? , it’s just a, someone’s representation of it. And I think even now with computer simulated software and you can move stuff around and look at it three dimensionally, which is a hundred percent a step up from a flat textbook, but I think people underestimate the impact of doing like a cadaver lab with yourself and Tom and everyone else.

You get to see it in 3d, but you’re interacting with it. You have the proprioception of seeing it and seeing the variety and walking to the neighbor’s cadaver and going, holy crap, yours looks different than mine. And yeah, look, the heart’s in the same place, but to see all the differences and to work with your hands, to, I think you just get a much better, again, map of what you’re looking at, right?

Cause of that proprioceptive interaction with it on top of the visual aspect.

[00:21:18] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Absolutely. Absolutely. And I’m, like I said, I’m playing in, you mean some other labs these days. I’m actually doing work with k and m labs, which is with also Leslie Kaino, who is part of the breathing project. So I’m playing with, and I come from the yoga world as well that we’re playing with applying it to movement.

As I mentioned too, I’ve been in Germany and getting to dissect with an international team of dissectors and I’ll be working to a more specific lab for athletes coming up. So there’s more to come in applications. But you said, as you said, anybody’s good lab that’s out there. If you have any, just a few different comparison points you’re going to see and learn in a really profound way.

Those donors are definitely our biggest teachers and we respect that in such a huge way. One thing I should always say too, I think most of your listeners are savvy enough and know this, but the donors now international. Are definitely donors. There used to be a time in anatomical history, we had some kind of iffy sourcing of this, but these are people who wanted other people to learn from their bodies.

So they’re giving that gift. And I often liken it to looking at a seashell. We’re no longer seeing the living creature in it. it’s the remains of that shell. But we can take a lot of guesswork of what happened in that body and in movement and what shaped it in the way that it appears to us on the table.

[00:22:55] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. So the next question I would ask is I think so for shape is interesting to me because it appears like you can, I don’t know if you would agree with this, but I think given enough time and stress, you could probably change almost every tissue because I’ve seen bony changes, which, Wolf’s law, soft tissue, Davis’s corollary.

Yep. That, yep. Basically any tissue is just responding to the stress on it. And it’s fascinating to get an idea of how people were in what positions most of the time. . And how much of that do you think is creatures of habit and deciding to stay in positions versus at some point you have such soft tissue and maybe.

Hard tissue adaptations that you no longer have as much option to get out of that position. Does that question make sense? It’s kinda a chicken or the egg. You’ve got some genetic things that you might be born with. For example, I was born with two holes in my heart and had a atrial septal defect and a ventricular septal defect.

So my heart responded by getting like really big and going into heart failure. Because of the inefficiency of it. So I think you have some things that you’re initially set with, but I think a lot of things, especially in modern society as a result of not us being aware that we are adapting to our environment and we’ve adapted two different position.

[00:24:19] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yeah I’m a really big advocate in looking into environmental space. How yes, we shape what’s around us and how that internship shapes us. So that, goes as far as, the buildings that we live in and then work out of. And there’s all sorts of interesting things. There’s a few architects out there Columbia, their medical college have one building that I love because it’s been done with all of.

It’s crazy ramps. Oh wow. And different surfaces so that people, the medical students when they’re in this tight little space in New York City have to negotiate some very different terrain within a tight space. I think that’s brilliant. Or, the way a building can even make you feel as far as sense of space and how you negotiate around other people.

I get out on a trail religiously every day, every type of weather. But part of the reason I do it besides being out in nature is, hey, , that really is restorative is the different terrain cuz it’s unpredictable. I cover a lot of acreage. I vary my pathway I take every single time. But I would never have the same trail twice anyhow, because one day is humid and damp.

One day the rocks have shifted and changed on the steep incline, whatever it is. These things change and I think we’re used to, in modern society, living in very. Flat terrain places without a lot of challenges or variety. And we know both , psychologically, body-wise, we need challenges or the body, the first time it faces something that it’s not used to.

Is way over challenged. We need that, that in space, if somebody, again, we see a lot of elderly donors at our tables and any lab you will see that collapsed chest, the rounding against, sometimes the upper elevation of the shoulders is because towards the end of life it’s hard to breathe and this helps that out.

But this becomes locked in place. You can see who had walkers and who had wheelchairs. Just written in their body because it’s been in the tissue for a while and for whatever reason wasn’t challenged in other ways. Sometimes we, again, get into habit where, okay, that must be the way I am, therefore I can’t break through that.

Like I said, working elderly clients is really fascinating because of all we can still do and oftentimes doesn’t and gets written into the tissues. The science keeps changing. We know with fascia somewhere around six months to two years, the science, like I said, keeps changing a little bit.

Those fascial tissues, reshape and reform, we know muscle fiber reshapes a whole lot quicker. This is why, again, a lot of athletes doing explosive training without thinking fascially will rupture fascial area. Achilles tendon rupture or what have you. So some of this, yeah, I think it’s chicken in the egg.

It’s hard to say completely, I want to have, The most interesting possibilities for myself for as long as possible. And so with that, I look too to vary my movement in different ways and I think that’s, I don’t know if that answers fully your question, but one thing I was gonna say, I’ve worked in my past too, I’ve been a dance movement therapist.

I’ve been all sorts of different things along the way. I’ll relate it. But if you have somebody, for example, with cerebral palsy, that’s sling. Of tissue is actually holding them in place. . So I see sometimes the mistake that a massage therapist who doesn’t have maybe as much training with that population would go in and try to release what’s, what we would call lock long.

And that would be a mistake cuz that’s their structural system. So we have to think about for what body, for what they’re dealing with in their life and why certain things have shaped into being and shape in general. Boy, I find this fascinating. It just, that’s part of even what I look at in my book as far as form, as far as everything else, what kind of, what shapes us and why, how do we do this long-term overtime and also short-term, and into our lifetimes.

But I think there’s a lot of possibility for ships and change what comes in different levels. It comes from the individual, but it also comes from, okay. What environment do you place yourself? Are you walking somewhere daily? Are you always getting in your car? Are you giving yourself, whatever those choices are you in a environment that feels safe to walk?

This is a big one too. All of those sorts of things come into play about how we adapt and move our bodies. Really important stuff.

[00:29:26] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. The examples I think about related to that is I’ve had a couple just consults I’ve done after the fact that they had some knee issue, they had maybe a partially torn acl.

One female athlete had a missing acl. L it’s been missing for 12 years, wasn’t competitive anymore. And the one case she unfortunately went in to have an arthroscopic cleanup. And then after the cleanup, the doc’s oh yeah, we found all sorts of heinous shit in there. And we cleaned it all up and she’s, the doc’s showing her the pictures of how good it feels.

She’s oh wow, this is great. And her knee was a disaster, right? Yeah. She had more pain. It was unstable. And I’m thinking, and this has happened a couple times, and I’m thinking we have this tendency to make everything look pretty and, be symmetric, but in her case, that scar treats you and God knows whatever else in there.

Was probably holding her knee again, . Because she was missing the structure. The body’s gonna try its best attempts to, fix it and add, structures into there, whatever that happens to be. So I always think of that as an interesting case. And then the variability, I always think we’re becoming like a nation of sea slugs.

I’m sure you’ve probably heard the story of the sea slug before. That’s this little critter that floats through the ocean and once it finds a rock, it attaches itself to its rock and then never leaves again. And then it eats its own brain cuz it doesn’t need to move anymore. . The food just kinda flows by.

And I just think of, even with clients I consult with, it’s Hey, that’s cool that you’re doing cardio, you’re doing strength training. Great. But what do you do for recreation? Like you said, do you go hiking? Do you go on a different trail? No, I run the same loop all the time. Oh, you’ve got lateral knee pain on your left side only.

Have you ever gone the other direction? No. You can’t run the other direction. Like how much, and these are not like elite level athletes. Because like we talked about asymmetric athletes, if you’re a high level major league baseball pitcher, you’re going to be highly, you’re gonna be as asymmetric.

That’s your job in, in life. But I just think of how little recreation we’re doing and how even just a simple act of catching a ball, like the amount of, I always think of if you could train a robot to catch a. Like the tasks that we sometimes just take for granted are actually ridiculously difficult.

And it just feels like when we’re not playing in kind of unfamiliar environments where we know what’s coming, but yet we don’t. So I think a ball sports like tennis, golf, obviously I do surfing, kiteboarding, that kind of stuff. Like I think you just, people need to go play in a safe environment but have some variability that they can’t 100% predict all the time.

Cause I think we’re just wasting some of those precious circuits in our brain.

[00:32:10] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: I totally agree. And then we’ll swing this conversation to the young kids and play and how, where that all begins because there has been research done too. Robert Loe did a thing Last Child in the woods or whatever the name of that book was.

But he did research about just aiming from the eighties how that circle of exploration space for kids has gotten smaller and smaller. Yeah, it’s crazy small now. And you and I know that too, probably our past childhood. I’m, in my fifties these days. You went out and you just played, you were free to explore space, and I grew up initially right outside of Chicago that was very urban going down in sidewalks, but we were sent outside with the bike and you went off and then, new England where my family moved to it was explore, just explore, go out in the woods and explore and that sort of curiosity.

And I think curiosity is just such an important thing, in life movement actually, it’s all the same. If you lose curiosity. , you lose so much. So again, the person who’s always running the track the same way, clocking the same exact number of miles, because some Fitbit tells them. So it can be a, good incentive, gamification and fitness.

And yet let’s have a curiosity about, exploring something different, playing differently, like you said, getting out there, kite surfing, whatever it is that’s unpredictable. And I think, as too, part of what I do in my recreation is kayak guide and . And I’ve done trips around the world kayaking.

And that teaches you too, to be aware, but there’s never a predictable path. Water is very unpredictable and you’ve got to be alert to reading patterns, which I think is just so fascinating to me. But it also means you have to stay resilient and responsive to whatever movement gets thrown at your anatomy.

So that, yeah, those sorts of things I think are really important. Play is important. And what have we done these days to Sports ? We have made it so rigorous, so unfun, I look at, youth, kids programs. Sometimes there’s not that spontaneous learning. Or failure and, movements, sometimes we’ve gotta see what works, what doesn’t work in order to explore, Michelle Delco too, he was finding out his viper system was all about looking at, the kids who trained traditionally in the gym versus the farm kids coming into the ice hockey rink.

And the farm kids did so much better than the kids training, partly because why they have unpredictable load. They have unpredictable vectors, angles of where they’re throwing that load that trains them to be more resilient for, again, , passing the buck, and doing something that may come at you when you least expect it.

[00:35:28] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yep. Yeah. And the most insane part about that too is that I agree a hundred percent with all of that. The hard part is talking to parents. It’s a very tough sell. So I don’t coach any kids anymore. I couldn’t deal with their parents, to be honest. I did it with a very short period of time. Oh, the handful of kids I worked with, they were all great.

Worked with the women’s soccer team for a while. They were awesome, their parents were insane. , I’d always tell them, which is true, like the Russians back in the day, like ethics aside, right? They could do whatever they wanted for better or worse, usually for worse. But if you look at a pure perform, That system, for better or worse, allowed them to try a whole bunch of stuff that they only gave a crap about performance.

And I think with the exception of gymnastics and maybe ice skating, because those are body weight, highly dependent. , they found that early specialization didn’t even work. Like their athletes would peak super early, but they couldn’t compete in the games, so it wasn’t really worthwhile. So they ended up having them do like aerobic phases.

Gymnastic phases. They had all these different H, what it looks like is just highly variable movement. And that those athletes were, later on, they specialized were substantially better. And even see that now, like a lot of times good athletes were just good athletes. Michael Jordan, I think played baseball in high school.

Tiger Woods played multiple sports. A lot of the top superstars, I can’t even think of a case where maybe Tiger is an exception with golf, but most of ’em didn’t hyper specialized. So even from a pure performance standpoint, it breaks down. But yet the simple story of, oh Junior is just gotta practice this thing.

And they do get better. But again, at what cost? To win the fifth grade, like little league tournament. I don’t know. Anyway, preaching to the choir here. .

[00:37:19] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yep. Yep. . Yeah. No, and I think too we need people resilient for life cuz look at, the extremes and then how people are aging end of life.

It just, we, there’s, I think there’s more possibility and this is where all of this has application. Like how can we make this applicable for our clients and for who we work with and why should we care? , all of those good things. But you go inside too. Go back to lab, you go inside those bodies and it’s fascinating.

This was something too, I’ll throw back to one of the early labs I did with Gil that he always used to say is, there’s more that’s going on. In that body on their very least viable day that they ever had then is wrong. And we tend to look for sometimes those mistakes. But it’s interesting to see, okay, what is really going on and how creative we are at coping with it.

But what could we, do that would be. Better. And that’s where I have curiosity always too. And like I said, curiosity in science, in movement, everything I think really carries us far when we go to choreography or to, choreography has its point, but I mean that in the sense of we’re always doing the same pattern to learn something.

To me that’s not learning. We’re we’re not exploring in a really thoughtful, creative way. Creativity, making some mistakes, it’s all part of it. . Yeah. Part of

[00:38:57] Dr Mike T Nelson: being human . Yeah. And that’s one of the reasons I like kite surfing. Not only because it’s fun, but it’s one of those skills that’s harder to learn, like I imagine surfing.

, I have only gone surfing a couple times just without a kite. But it’s one of those things where there’s no free lunch. Nobody comes in day one and has it mastered. It’s just too complicated. And, I’m sure golf is the same way, high level dance, like anything that’s a high level, it’s gonna take you years and years of practice, but you can get better.

And I just get nervous sometimes about society. People don’t want to try. So even training clients, right? Like I’ve had, I’ve lost count of how many clients. I’m like, okay, you’ve never really done a squat before. Let’s have you do a golet squat. Here’s what it looks like. , they do a rep and they’re like, oh, this is so horrible.

I can’t do this. I’m like, how many times in your life have you ever done this exercise? They’re like, never. Okay. You’ve never done this before. Like, why do you think you would be amazing at it? The first rep is always your worst rep. But I think as a society we’re moving away from, it’s not safe to quote unquote fail or look bad or just, there seems to be a thing of trying to skip part of the learning process.

And you can do things to accelerate it, but you have to make mistakes. That’s just, that’s how you learn. Like you can watch tons of video, but when you try it, it’s probably not gonna look very good. And youhow, some people are better at that than other people. . But I dunno, I just get nervous. Cause it seems like it’s not like good thing to make mistakes.

And making mistakes is just part of the learning process and there’s no way.

[00:40:37] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yeah, absolutely. I, my biggest area that I teach these days is actually, at a university I teach at Pace University as well as guest at Rush Medical, but I teach university age students and when I teach both anatomy and movement.

When I teach my yoga only courses, for example, I turn ’em around. I don’t let ’em face the mirror. I don’t let ’em have their cell phone out. Nice. Don’t let ’em do any of that because I want them to be comfortable not having to watch or be watched and by, but by anybody but me. But To be able to be okay making mistakes.

You have to learn, how to fall safely. If you’re doing arm balances something like that. But there’s, there’s nothing wrong with not doing things perfectly. That’s why we call these things practice. And we’ve so pulled away from that. I think partly because we’re always on social media where there’s filters and people can fix things and take the best frame or the best couple seconds of, performance and have done it over and over again.

But what most people don’t see is those behind the scene things. And that’s what’s fascinating to me. How do you learn? That’s interesting. I don’t really care about the, final look of something as much as, does somebody have the ability to learn and, change and get, again curious.

[00:42:07] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. And I think we lose perspective on how long it takes even high level athletes or performers to do what they actually do. Like it was Alex Honl spent, what, he spent like a year and a half to do that, practicing the climb that he did, , just kinda see like the final thing. And it’s crazy.

It’s just bonkers. I’m afraid of heights. I could, my palms are sweaty just talking about it, , right? So it’s absolutely bonkers and insane. To him, it wasn’t a big deal because he had practiced it so much that he knew he could do it. Granted, you’re the safety there, so you have to do that. But we don’t see all the time that goes in.

Or like I think of some of the Red Bull videos, like Danny McCaskill is done with crazy stuff on a mountain bike and it’s pretty cool. A lot of times at the end they’ll do the little blooper reel. Yep, exactly. And they’ll show doing the same trick over and over to how many times he just fails doing it

But you watch the whole like one trick after the other. And you realize like sometimes those are done in a session, but a lot of times those are just pieced together. So you’ll work on one thing, get that down, maybe try to add something else. But the goal isn’t to do it as one flow, as a competition.

It’s to create a piece of video, a piece of art. So it’s nice at the end to see all the failures that went into it so that we don’t leave with just this image of, wow, he just did that in an afternoon. It’s no, he was working on that for probably a year, probably almost a decade for some of the other skills.

The prerequisite to be able to do that. Absolutely. But again, we

[00:43:32] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: don’t see that a lot of times. Absolutely. I think that’s really important. Yeah. And some of the, especially the rock climbing, I’m right there with you, but , my younger son’s a rock climber. Oh, okay. But it’s, it’s fascinating because it is, it’s the, it’s practice with anything, whether you’re, again, piano player or you’re, golfing, whatever it is, there is that high level of the top.

Failed a lot to get there, . And, but with each again, there was a learning process and there was also the ability to, again, play in different areas of the body and to be more resilient to it. Park core is fascinating for that reason too. And you see there fails , there’s some life and death almost fails.

But as far as Amy talking, myofascial bodies, what they learn to do is actually roll to take the impact of everything and to be loose, to be able to let that distribute throughout the whole body instead of tightening, which is our response, and most of the time to fear, which tends to, of course, shatter, wrists, everything else when people freeze something they’re doing in nursing homes now is teaching some of the elderly patients how to fall safely.

Yes. And to do that sort of thing of rolling, not park core level per se. Yeah. But it’s based on that same idea of how do we. How do we explore these things? How do we learn to, how do we learn to fall Modern dance, which I came out of that whole world, many modern dance classes, half your classes based on fall and falling and learning how to roll out of that and how to recover from that and do it safely.

You get knocked up a little bit to get into that point, but you learn how to play with all of these different things goes back to play again.

[00:45:35] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. And if you’re better at that skillset of falling, your odds of tensing up before it happens are gonna be a lot less. But again it’s a weird thing that people don’t think of practicing either.

And it, I think it’s gotten better, but to me, for a while it seemed like the teaching falling was almost like high level martial arts. Like some of the stuff I saw years ago. It didn’t take into account like what your innate reflexes would be. It’s okay, do this advanced parkour thing where your arms all the way out here and you’re rolling all the way up on your shoulder and I.

Yeah, for those athletes that makes sense with, hundreds to thousands of reps. But a buddy of mine taught something that was more simple, which was, yeah, put your hands in front of your face, but then use that to distribute your load. Yeah. Because the amount of reps it’s gonna take you not to do those hardwired reflex things is crazy.

So just do the hardwired reflex thing, but modify it so that you. As stiff, you’re dissipating more force. Not try to rewire how your body is reflexively wired

[00:46:41] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: either. And that’s where learning why are we acting some of the way, how have we been shaped over our evolution is really important because as we know, front of the body, more fast twitch fibers, we’re protecting this really vulnerable area than all our quadriped friends.

tuck underneath themselves makes a lot of sense. But we’re upright, we’re bipedal. It’s a really weird place to be in an evolutionary sense. So we have a lot of challenges coming on upright and to understand that in terms of anatomy, understand why, again, both fear, stress, all of these things pull us forwards.

The head forwards. It makes, the more we learn about all of this, then we can start to intelligently work with that and recognize it. We don’t recognize, we can’t really change. And I think that’s so important, like I said, in any part of dealing with the body in any shape or form. Yeah.

[00:47:45] Dr Mike T Nelson: Related to that, with. The fitness stuff. Do you do you program a lot of extension or the opposite of flexion because people are in this sort of flexion, working at the keyboard and hell, I’m probably sitting in that position. , yes. Right now. Now do you try to program the opposite of that to try to get some sort of semblance of balance or to try to keep them outta that as much?

Because it seems like the more you get closer and closer into permanent flex, like you’re getting closer to.

[00:48:18] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yeah, and that’s a really good question. Because came out of the world where, I was trained in labon movement analysis and barini off fundamentals and some of this thing that comes out of both crisscrossing with dance and movement therapy worlds.

We also look at things of you can’t go. Immediately, usually from one extreme to the other if the pattern is really tight in there. So to have somebody who’s pulled in like this and go, Hey, do a backend, yeah. , that’s gonna be , not happening. And yet we do have to counteract why would we, again, keep doing chair pose and yoga when most people are in chair pose, literally every day, right?

So I do look to counter that, but to soften it, again, if somebody has sciatic nerve issues and everything else, we’re not taking them right away to some other extreme. But I’m looking, okay where is there space for that nerve? For whatever reason, that’s getting compressed. So I’ll look oftentimes for that mid-level.

Intermediate point and then start to move into that. But not to go right away from one extreme to the other. However, if you have somebody who is much more movement savvy and who has that in their body system to go through that a little bit quicker, then, you mean for my own practice? I go, oops, I’ve been sitting a lot, I’ve been teaching a lot, I’ve been actually running a lot, this way I do need to get myself into something a little bit more opposite, but I have a lot more play with that normally.

So it depends, but I wouldn’t go opposite. Opposite, which is where you see that happen in a lot of sports as well as yoga, as well as, anything else. People just go right away for the extreme or weightbearing when, most of our people don’t weightbear, like on their hands during a normal work week, and then suddenly the first thing you do is a downward facing dog.

That’s rough. If somebody hasn’t been playing with that. So I always look for getting there, but not from one extreme to the other. There’s a pathway that you have to play with.

[00:50:30] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. Yeah. The phrase I think of is, my buddy Adam Glass said this and it applies to programming and movement, and he just said, just move where you can.

Yeah, so I’m always thinking with the client or with the person. What movement can they do that might be adjacent to what we’re trying to go away from? It’s probably not the end goal because we can’t get them to do the end goal right away, or they probably would’ve figured out on their own anyway.

It’s can we get ’em closer to that path and then over time Exactly. Closer, closer and closer. But again, in fitness, that doesn’t sell. It’s learn how to do a hundred pushups a day, or whatever the extreme thing is, or couch to 5k and there’s some good programs with that kind of stuff, obviously.

But it, yeah, when you talk about the resilient part too it always mystifies me and it’s just amazing how yes, you can have injuries that happen to the body and yes, we tend to focus on all this stuff that’s quote unquote wrong, but most of the stuff is correct and the fact that the body will perform as well as it does in the face of all the other things that we do to it just boggles my mind.

If I wouldn’t put sugar in the gas tank of my car, I probably wouldn’t make it around the block. You have people who eat just a horrible nutrition for years, decades on end. You can have people who don’t do a lot of movement and they’re not in the best shape, but they’re still upright. They could still do yeah, some stuff.

To me it’s just. Amazing on both ends of the spectrum, how much abuse the body can take and still keep going versus the elite athletes where, sometimes those small, tiny things at that level do make a difference.

[00:52:08] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah, and it’s exploring all of that, definitely. Yeah. , he said it. I can’t add to that. That’s well done, .

[00:52:21] Dr Mike T Nelson: So we’re about an hour, we’re into the conversation now, but I’ll finally ask you like, how would you describe what is fascia, right? So that might be a new, we’re talking about movement and just different philosophies, but in terms of fascia, that may be a new word for people or they might have heard of it.

Like how would you define what fascia is?

[00:52:39] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: In the first place, I do let people know the definition keeps changing, right? And that surprises people right off the bat. Because, it’s a dissectable aggregate of, these, there’s very scientific definitions in basic terms. We have this restaurant mixture of different things, the fibers, the collagen fibers that are in there, the water, the glyco, amino glycans, the slidy gli things that, putting all of these different things together and, having the different combinations make up different parts.

Because when we parse it into that thing, we go, okay, so that’s how I can understand adipose being part of this fascia as well. As well as, again, intermuscular septums is white areas around the muscles, but also what intertwines. So the reason why, the orange image gets used so much is because basically the white of any oranges is cellulose.

is the fruit fascia. So it’s a very easy way to start to dive into that. And because I am a dissector , when I was little I not only peeled apart the individual segments, intermuscular septums, I also did the individual wrappings sometimes around those teen Oh, nice. Tiny segments. Which is like the FASA that wraps around any muscle, individual fibers on a very small level.

So when we start to describe that, then we can say to a client, okay, the reality of course of the orange is the hole. You don’t see any of this separation until I peel it. But why does it peel easier in certain ways? Where it peels easier is where the fascia often is. Sometimes it’s used for strapping too.

But think about it, right underneath the skin, that white area is much more mobile. That’s where there’s some movement. Again, I appeal easily, I separate between those segments, between the intermuscular septum. That’s a good thing. And if I wanna eat an orange slice, if I’m moving, I wanna have some ability to slide and glide between those fossil septums, or I’m gonna get stuck, if my hamstrings are glued together as one group and I can’t mobilize that, I have less possibility in my movement.

Or if my quadriceps, if only the rectus formo is really active, but nothing else is working and nothing else is sliding and gliding, that’s gonna restrict me as well. So we start to sometimes use this imagery into it. And why we’re also, a lot of us are creating more images to share with the world in different ways, like the project that was the PLA nation project.

Just to have people starting to think about these things in new ways. As I mentioned, as part of that international group, the FAS net PLA Nation project group. And when we were done with this whole thing it’s permanently, it was in Montreal for, again, the Fascia Research Congress, but its permanent home is in Berlin.

And the first time I visited in Berlin, it’s set, in a lovely room really with a lot of different explanations, educational explanations around it. But it was watching people’s reactions come into that room and go, wait a second, what is this? I’ve seen muscle person, . . I’ve seen circulatory person, I’ve seen the skeletal system, but what the heck is this other rep representation of the body all about?

And to start to think about this in that holistic way is really interesting. And then to go again, what shapes us into different forms within that, how do we play with that? How do we keep it healthy? What’s some of the latest research done? All of that. There’s a lot going into nutrition, which I know is a big love of yours.

As far as is again, how can we keep that fasha healthy and viable? So yeah.

[00:56:48] Dr Mike T Nelson: Why do you think fascia appeared to be bypassed for many years? Which just from my own aspect, my bias is, I think when you look at embalmed tissue a lot, like we talked about the beginning of the show, you just don’t really see it.

And I remember when I took a anatomy physiology the first time, in all honestly. Yeah. I wanted to learn it. I thought it was super cool. I got to work on cadavers. It was. But I was also hyper worried about trying to pass the class, so passing the class involved. Identify the origin, tell me the insertion, , pokey things in the tissue. Tell me what that is. So it almost seems if you’ve ever seen the old you can look it up on YouTube. It’s called the awareness drill, or the guys are passing the basketball back and forth. Yes. And I’ll give it away for people are listening, but there’s this gorilla and a guy in a gorilla suit goes right through the middle of him.

I’ve seen it . And you ask people this who’ve never seen this video before, and I think it’s like how many times of the person in the black jersey pass it to someone in the White Jersey or something like that? And you ask him at the end, did you see anything else in the video? Everyone’s no, are nothing weird, nothing El no

And then they’re finally like, did you see a guy in a gorilla suit go through the video? You’re like, what? There’s no guy in a gorilla suit. And then as soon as you mentioned, you watch it again, you’re like, holy shit. There’s a guy

[00:58:04] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: in a gorilla there. It’s suit. Yep. There he is. Yeah. And I think you hit upon it something I really love to talk about.

I put it in the beginning of my book as well. I’ve written about it for some, different talks too. What we’re not aware of, what we don’t name, we lose our ability to see hundred percent. And there is this wonderful children’s book called The Lost Words, which was done, a couple years back.

And it was done because the Oxford, children’s dictionary was taking out really common words like dandelion all these different things. Yeah. Because they were like kids don’t need to know that one anymore. Oh, Jesus. And the authors of this book Yeah. Where had the same reaction.

They’re like, we need to make a book and with beautiful illustrations to make sure people hold on to these words, to these things to know about them. Because what we have out of our vision, we lose. And there’s many other writers and other thinkers who’ve thought along these lines. Fascia’s an interesting one historically in here too, because people like Rie and Jacobs did a beautiful atlas couple centuries ago that had these big pictures with the fa Septums very clearly shown the muscle fiber taken out.

It gave inspiration again to some of what was done at the Fasa Plastination project. So it’s been there before, and that was almed tissue. Now, there were times during almed tissue for practical reasons, you’d wanna get off that ATIP post layer quickly and efficiently, because again, you didn’t have refrigeration, you didn’t have, necessarily time on your hands to work with tissue in a way that made sense to, close up at the end of the day.

As most unal tissue labs are about five days cuz that’s about what we can handle with bacteria coming in it’s nature.

[01:00:03] Dr Mike T Nelson: And that’s with refrigeration and modern technology

[01:00:06] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: at night. Yeah, it does help, it helps delay that process once that scalpel comes in. We’re fighting this battle with air and bacteria and everything else that’s meant to happen.

As far as that your right spot arm in bone tissue, then we were also looking at scraping away everything and just looking at muscles which were considered to be important. Even Theus, who many of us love in the Fox world. Did a lot of very lean bodies, partly cuz he is working, with criminals that were the body, not so readily donors, but were the ones he was working with access.

So you didn’t see a lot of that fossil layering that was taken away. So there’s also that. And then as you said, the medical model became very clear on, we’ve gotta name it. We’re gonna put these little things in place and we’re going to have this scraped away. And netter you mean for all his artistic brilliance to have both things going there.

took away a lot of the fascia. . So if we didn’t see it, if you don’t learn it, I mean in your, children’s book, if you don’t see it in your anatomy atlas, you don’t think that, think about it. So it’s a shock and a revelation like, you mean in the plastinated model for people to go, wait a second, what the heck is this?

I don’t know what the name is. And why does it keep connecting? As I mentioned I’ve guessed at Rush Medical and they were loving that I was doing involved tissue, and I had, that’s a lot of, oh, that’s cool. The surgeons and everybody else come in and look at what I was dissecting as a project, cuz they were like, this is great.

This is what we see in surgery, but not what we usually see in the table. Embalmed tissue. So it is an interesting thing that shifted in change. Of course if your teaching, again, over a semester having that embalmed tissue makes a lot of sense. And yet there’s real big value in seeing this uninvolved and being able, especially for movement people, we really wanna see that and get those connections and understanding.

It’s a different map. And I guess I can say that, in clear terms, we’re looking at any anatomy atlas, any system of thought, even. My fascial connections are maps, and this is, this has become a big thing, hot thing in the whole world are on social media. Dare I like, have people come after me on this one.

But people get, like you said in the very beginning it’s a similar thing. People are in one camp or the other, and I go both can exist. This is more physics. Both can exist at the same time. And can we hold that thought? Because even any models of connection are useful if they make sense in their connectivity.

And we’re oftentimes looking at connections that have made sense or replicated, but there’s still a model. There’s still a roadmap. But I, sure, I want a roadmap. If I’m going down to a new client Oh yeah. Who I’ve never met before, I definitely want the GPS to take me and tell me, where I’m going.

Because otherwise it’s okay, I’m gonna guess it’s the, 18th street over the whate. It’s another map. It’s not all a reality, but it can be a useful way to parse it out. It’s another construct. When we eliminate, Any ability to see other maps, other ways of saying we lose something.

So I’m always curious to look at all of these things, and to learn it all. And if I’m talking with somebody else where I want to have those specific names, I want those names so that I can have a conversation and then expand it into, Hey, but look at this. This is a cool connection or a way of seeing, you might not have thought of before, there’s a relevance here for something else.

So I think that’s why, with my book too, I like conversations between people and sometimes to have a really meaningful conversation, you’ve gotta learn language, and then be ready to change languages or hear a new language for yourself. And I think fascia is that for some people it’s a different language than they’ve spoken before.

It’s also, interestingly, and you know this as well too, almost becoming. A catch word in too much. The buzzword where it just gets thrown out there in any shape. Report. Gotta train your fashion, bro. Fashion, everything must be faa and it’s, that’s the most important thing. And I’m like, wait a second, I love it.

It’s not everything. Nothing is everything. Just to have that caveat in there too.

[01:05:04] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. I’m trying to think of, did Da Vinci ever show any fascia stuff? He had, I can only think of a couple that he might have, but I’m fuzzy on

[01:05:16] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: it, to be honest. Connections, which are actually the arms in particular kind of show some of these connections a lot more fluidly than other people did.

We do think he did probably in the neighborhood of 30 dissections during his lifetime. But it wasn’t, there were things he got wrong. The one that everybody thinks of is, again, female anatomy, because again, when he showed the uterus and some of what came off of it, that was really bovine anatomy.

Not female anatomy, and the shape and size were wrong, but he was piercing, piecing together best he could from different things he saw, but a lot of it is fairly accurate. But just still in that tradition, it was a lot of, it was cleaned off of at least the superficial fascial layers. There’s still not as much of that as brine Jacobs did, or as we see in some other early anatomy that was showing some of those more mild fascial connections.

Yeah. Interesting

[01:06:21] Dr Mike T Nelson: stuff. What are your thoughts about teaching origin and insertion, which I know sounds like a very. Simple question. I’ve talked to Tom at length, probably ad nauseum and boring him with this question, but for me, when I took anatomy and physiology at first, right? So you always learn origin insertion.

That’s the way it’s classically taught, and I think there’s a time and a place for it. I’m not saying, throw that out entirely, but I realized once I got to doing fresh tissue and looking more at it as a systems point of view, again, like you don’t see what you don’t see. I was so hyperfocused on always looking at origin and insertion that I missed other stuff that was very obvious.

So in my example, I took a class A P r I from Ron Ska who was teaching it. So Postural Restoration Institute, and Ron’s yeah, did you know like the other end of the SOAs is actually, the lumbar spine. And I’m like, what? I’m like, okay, sure, yes. What’s there? And he is and then it disappears into your diaphragm.

Like your diaphragm. What? I didn’t learn that in anatomy. Physiology. You’re full of crap. What is this? I talked to ’em even after class. It’s no, we did it in dissection. I’m like, how did I miss this? So I go to look at the anatomy books I had growing up, and in a couple of ’em, you can see the area where it goes to the diaphragm and it was indeed cut off, right?

So it was not necessarily the picture was inaccurate or wrong, it was just hyper focused on a origin and insertion. Obviously, Tom’s got some great pictures, of this and things too. And so I have. Love, hate sort of relationship with it. Cause I taught anatomy and physiology and the second time I taught it, I feel bad for all those poor students, because it was a 300 level class and I was trying to ride the line of yes, you must know origin insertion.

Yes, you must know basics, but don’t let that just define everything that you’re ever gonna look at again. And I think they just looked at me like a two-headed space alien, cuz it didn’t have a cadaver C portion. It was an online thing. It was a weird setup to begin with.

[01:08:25] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yeah, no, and that’s a really good point.

The so as diaphragm, the diaphragm, the legs of the diaphragm definitely interdigitates so beautifully in a of the cadavers that we’ve seen over and over. What’s interesting is there are some historical precedents for that. But they’re not usually in the clinical anatomy

[01:08:45] Dr Mike T Nelson: atlas. I couldn’t find them in the clinical anatomy book.

As I went it bugged the shit out of me and I went back and looked and I couldn’t find it. .

[01:08:51] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Igar Bari, who was again, physical therapist who worked with people like Lomax, who’s most well known for the Smithsonian Folk Way recordings. She was also somebody who was highly interested in just movement, in environment, in all of these different things.

And she has a lovely illustration in her book that basically is very similar to Tom Myers, looking. Illustration, which shows again, the diaphragm going right into the SOS and being a continuity and, hey, doesn’t this make sense for a lot of our deep movement that we’re doing? So that’s, yeah, that’s a really clear one.

Another one I’ve seen a lot in anatomy labs is when you take the sarus anterior to rhomboids, which no traditional anatomy book will have that they have a hard ending. Yep. And yet, if I turn my scalpel around it is very easy to make that continuity, which does make a lot of sense to me when I’m playing with something like a chatter onga in yoga or a traditional pushup, and playing with somebody who has, again, wing scapula of how do we stabilize it?

Could we stabilize it from sarus anterior, . Again, I think it’s that curiosity to stay open. It’s still it’s a tricky place to be. I am lucky I came into anatomy sideways, , go back, learn some more traditional anatomy, then came back again. I already had a little bit of that open mind.

But it’s a little bit like, again, learning your skills on the piano, you sometimes have to learn that to then improvise. , or like I said, to have the convers. Again, we origin insertion. Does the body really care about it? Not whatsoever. , right? Some of it isn’t so accurate, but it is a good, way.

It’s a concept again. So where is it useful? Where is it not? Where does it cripple you? I think that’s the key in any of these things is when you get absolute about anything , you gotta go stay open and go, okay that’s a good thought process, but what, what is viable about it?

What’s a good idea? What is not, maybe scientifically able to be reproduced and those sorts of things too. Yeah, I it’s not I’d say throw it out completely, but we do spend a lot of time learning origin insertions when it, may not be necessary. So who are you learning this for?

What’s your reason why, you know that’s where, if I’m changing things or learning about nerve mapping and, I have to deal with that in a different way. There’s some interesting things there. Traditional anatomy we do a lot of this, but again, for some of your recreational people, do we need to know those certain things like where biceps are, origin insertion, that in the gyms, but you don’t see necessarily much more holistic look at the body.

Yeah.

[01:12:05] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. I’ve even recommended, I don’t have an answer for you completely. No, that’s good. I’ve even recommended people to take, like the course you helped Tom with and anything with fresh tissue dissection to a lot of people who’ve never taken anatomy who work as trainers, most of ’em, but don’t have much of an anatomy background.

And they always look at me like I’m just out of my tree . And I’m, they’re like, but I’m not gonna understand anything. This is gonna be so crazy. I need to go back to college and take anatomy physiology 1 0 1. And I’m like, You can, I think it’s helpful, but I, if I were to redo my education again, I would go with the inverse.

Yeah. Like I would take a one or two week fresh tissue dissection. Yes. You’re gonna be overwhelmed. Yes. You are not gonna remember all of it. Christ, I don’t remember half of it now. I’m horrible for teaching anatomy and physiology, but I remember the pictures, but I remember what it looks like and I can go back and refresh my memory for origin and insertion because I’ve stored the mental map of what it was, even though I may have forgotten some of it.

I can still remember a lot of the differences and the nuances and that type of thing. Even though I may not be able to name some of it. But I could go back to a 2D picture and pick that up because I’ve had exposures on both ends. Yeah. So my advice was just go do it. Yes, you’re gonna be overwhelmed.

But I think starting with a more accurate mental picture, even though you could spend the rest of your life studying it, I think is better than going from a 2d. Cuz I feel like I had to go back and unlearn a lot of stuff that was helpful as a foundation, but yet I think limited me from seeing as much as I could on the first dissection to the second, to the third.

[01:13:47] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yeah, absolutely. And I think it’s having that just mind open to it and to see what is actually, you oftentimes learn a lot more. There’s oftentimes been, it’s a sculptor, it’s a, engineer, it’s a whatever. , somebody coming in sideways into this, that actually sometimes has either the better skill set or dissection or, you mean, can conceptualize it, really accurately because they don’t have all the mumble jumble of what it should be in their mind’s eye.

They’re really open to just seeing what they see. And, you may remember too years back there was the book drawing on the right side of your brain that came out , and it was mixing up things and turning a picture upside down. So you just actually looked at the picture to draw it instead of going, oh, this must be a finger, this must be an ear that I gotta draw it.

What I think it looks like you throw all that away and you just are looking at shape at form. And that’s beginner’s mind in some ways. , you’re not, and here we go back, we’re bringing this whole conversation together, , but you’re not afraid to fail. Yeah. And hey, that’s where the real learning happens, when you can make mistakes.

Oftentimes too, people who are like, oh no, I messed up. Like Amy, you said before in the beginning. And it’s no, what did you learn from this? Yeah. Oh, that was really tough to cut through. Or, wow, that was much easier than I thought. Okay, why was that? And we can start to have a curiosity about what we’re experiencing, what we’re seeing, and again, I like to guide people through an intelligent way of going about this, but there’s always learning no matter what you do, if you keep that openness, that curiosity to it. So I just, that’s what I think is also so exciting, so interesting about all of this work. Yeah.

[01:15:48] Dr Mike T Nelson: Yeah. And for me, it was also refreshing to do it cuz the first time I took the class, I dunno if it was my wife or someone who was asking me, they’re like, why the hell are you taking this class?

I’m like, because you get to work on fresh tissue, this is gonna be so amazing. I’ve never worked on fresh tissue before. I’ve never done my own pro sections where I’m doing the dissection in a certain area. They’re like what are you gonna learn from it? I’m like, I have no idea, but I know I’m gonna learn a shit ton of stuff.

I don’t know what it is. Yeah. I just know I haven’t had that experience before. So by definition I know I’m gonna learn a bunch of stuff. It’ll be totally worth it, which it was. But it’s also refreshing to go in with, okay, I don’t have to memorize all the origin insertion. Like luckily at that point I went, I’m probably never gonna teach anatomy and physiology again.

So if I don’t, I’m not gonna chastise myself because I couldn’t remember everything I saw that day. The origin and the insertion, where the nerve was, all this other stuff. Just be open-minded to what do you see? What’s in front of you? What can you learn from it? And I ended up, I don’t know, I think I’m taking like 15 pages of notes over the course of a week or something like that.

But it was all stuff. There’s no way I could have predicted what it was gonna be before I had the experience, which is great. I think useful. Exactly.

[01:17:01] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Exactly. Exactly. And like I said, the visualization, the tactile feel of it, all of that is so important and really understanding. I got fascinated for a number of years in the brachial plexus and I would go through a brachial plexus dissection, just in between things.

teaching and your off time. I didn’t care about the names and I’d name ’em afterwards. Yeah. But I’m more cared about visually following the pathways and then having the curiosity afterwards of going, okay, now I can name it, oh wait a second, this particular body doesn’t quite match. Or, wow, how many of these do match the map?

What’s that all about? And why? Why would that work that way? So like I said, I think the biggest thing is just to stay curious, , stay curious in all of this. And it takes, you, takes too far for sure. Yeah.

[01:18:00] Dr Mike T Nelson: Related to doing hands-on work, I don’t know. Do you do hands-on work on people for massage or body position or actually whatever word you wanna associate with it.

Massage therapy? I don’t know. Everyone uses their own word for it.

[01:18:12] Prof. Lauri Nemetz: Yeah, actually I fully saved, that’s one thing I don’t do, .

[01:18:17] Dr Mike T Nelson: Oh, okay. You can do everything else. So I thought, oh, she probably does this too. . I